Alice Bulos and the rise of Fil-Am political empowerment

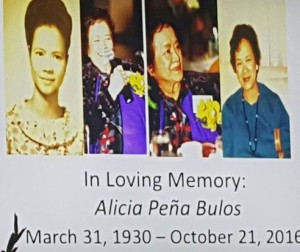

It’s ironic that the Filipino American community leader with the biggest heart of all should die of heart failure at age 86 at the Seton Medical Center in Daly City on October 21.

Or perhaps because it was so big, it eventually had to fail. The heart of Alice Bulos was the subject of tributes at the memorial service for her on October 29-30, at the Duggan’s Chapel in Daly City, by federal and state officials who knew her and by the community she loved and empowered.

Among the dignitaries who came and spoke highly of Alice were former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, California Lt. Governor Gavin Newsom and US Rep. Anna Eshoo. They joined virtually every Filipino American elected official in the San Francisco Bay Area to pay their final respects to Alice.

They came to honor the woman everyone simply called “Alice,” the one San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee called “the Grand Dame of Filipino American Politics.”

“She unified Filipino American politics, understanding how powerful the collective voice could be in advocating for the community. She made raising that voice easier through the Filipino American Grassroots Movement, a voter registration drive to bring more Filipinos into the political process. To ensure her legacy did not end with her, she mentored young leaders to continue advocating for those who could not advocate for themselves,” Mayor Lee said.

Started from scratch in 1972

Alice Bulos and her husband, Donnie, together with their daughter, Elizabeth, immigrated to the US in 1972 when Alice was 42 years old. By then, she had already carved a distinguished career for herself in her home country as chair of the Department of Sociology of the University of Santo Tomas where she obtained her master’s degree in Social and Behavioral Sciences. Her husband was a lawyer who graduated from the University of the Philippines.

They chose to uproot themselves from a respectable and comfortable life to accept the daunting challenge of starting from scratch in a new land. They held firmly to the Thomasian ideal that as you go up the ladder in life, you bring every one up with you.

When it was my turn to speak at the memorial service on Sunday, I introduced myself as the first Filipino American elected to public office in San Francisco when I won a seat on the San Francisco Community College Board in 1992. I was reelected in 1996, 2000 and 2004, serving three terms as Board president of the largest community college system in California. In all my campaigns, from the first to the last, Alice was always there for me, making phone calls, handing out flyers and helping me raise funds.

As we worked to unite and empower our Filipino American community, we met with other Fil-Am leaders from all over the US who embraced a similar goal. One of them was David Valderrama, the first Filipino American elected to the Maryland State Legislature in 1991.

When David visited us in San Francisco, he shared this joke that illustrated the difficulty of uniting the Fil-Am community.

DAVID’S JOKE

Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., Cesar Chavez and Larry Itliong all died and went to Heaven where they were warmly welcomed by God who thanked them for their work on earth, for constantly working to improve the lives of the people.

God noticed that the three men wanted to ask questions, and He knew what they were.

“Martin, my son, you want to know when your people will finally get united. I am sorry to tell you that it will take another 100 years for that to happen,” God said.

Rev. King started crying in shock that it would take much longer than he had thought. As angels comforted Martin, God turned to Cesar and told him that he was sorry but it would take his community another 200 years to achieve unity. Cesar Chavez broke down in tears and was assisted by the angels.

Then God turned to the Filipino leader and heaved a sigh. If God could only look up to Heaven he would have but he was already in Heaven so he couldn’t. Instead he lowered his eyes to look at Larry Itliong. After a thoughtful silence, the Lord broke down and cried.

Alice and I laughed heartily at David’s joke. “Yes, David. It’s impossible to unite our community, that’s why God cried!” we agreed.

But then, Alice became serious. “No matter what else we do in life, Rodel,” she told me, “we must make sure that we don’t make God cry.” That was what we resolved to do.

After Alice worked on my election to the College Board in San Francisco in 1992, we worked on getting Mike Guingona elected to the City Council in Daly City. It was a formidable task as Filipinos had been running for a seat on the five-member City Council for 20 years with no success.

How could this be possible when about 35 percent of the total population of Daly City was Filipino? The reason was the Filipino crab mentality at work. Whenever a Filipino is about to get out of the basket, other Filipino crabs will pull him down.

Mike Guingona

Alice was excited about Mike’s chances because of his deep roots in the city. Mike was born in San Francisco in 1963, moved to Daly City in 1965 and attended local schools. He graduated from the University of San Francisco Law School and passed the California bar in 1989.

When Mike’s mother bought a home in the Westlake District of Daly City in 1965, the deed of trust to her home contained a “Covenants, Conditions and Restrictions” (CC&R) document, which prohibited homeowners from selling, renting or living with anyone “not of the white or Caucasian race.” Mike’s mother was able to buy her home presumably because of her fair complexion.

This racial restriction was included in the single-family homes built and sold by developer Henry Doelger between 1947 and 1964 and comprising nearly a third of Daly City. Under the terms of the sales contract, homeowners who violated this provision would be obligated to pay $2,000 to each of their eight closest neighbors to pay for the assumed decline in the value of their property values.

Mike lost his initial run for the City Council seat in 1992, but the following year he won a special election to the council and has been elected five times since then. At the age of 33, Mike was elected mayor of Daly City. One of the first resolutions he sponsored was to eliminate the racial restrictions (CC&Rs) in Daly City trust deeds.

With Mike on the City Council, Filipinos began to be regularly appointed to various city commissions. In 2006, when Mike was mayor, the City Council unanimously appointed Rose Zimmerman as City Attorney, the first female and the first Fil-Am to hold that post.

In 2011, Mike successfully lobbied for the appointment of Ray Buenaventura to a vacancy on his City Council. Only one councilman voted against Ray, and it was a white member of the council, David Canepa, who was then the field director of California State Senator Leland Yee (now serving a five-year federal prison term for corruption).

Mike’s victory in Daly City in 1993 inspired other Filipino Americans to run for public office in San Mateo County, winning council seats in Colma and San Bruno. But Alice and others in the Filipino American Grassroots Movement she founded to register Filipino voters had their sights higher than Daly City.

Breaking the glass ceiling in San Mateo

San Mateo County has been governed by an all-white, five-member Board of Supervisors elected at large in a county that has a majority white population. It was an anomaly, the only county (out of 58 in the state) to not hold district elections.

In April 2011, Latino and Asian American voters led by Fil-Am Guy Guerrero filed a civil rights lawsuit against San Mateo County to compel the county to hold district elections to improve the chances of minorities to win a seat on the San Mateo Board of Supervisors. The plaintiffs prevailed in the suit and the county was compelled to hold a referendum on district elections, which was held in November of 2014 when District Elections won 59 percent of the vote.

With district elections, Filipinos in the northernmost District 5 will now have a better chance of electing a Filipino to the county Board of Supervisors. A Fil-Am candidate would not need to raise campaign funds to reach the nearly 400,000 registered voters in the entire county; he or she would just need to reach the 57,964 registered voters in District 5. With about a third of the voters to be Filipino or a member of a minority group, it would appear to be a slam dunk for a qualified Fil-Am like Mike Guingona to break the glass ceiling in San Mateo County politics.

But God will cry when he learns that the Filipinos in Daly City are not united. The man who stands in the way of Filipino empowerment in San Mateo County is Councilman David Canepa who shrewdly formed a political alliance with Ray Buenaventura whom he opposed when Mike Guingona nominated the latter to the City Council.

In exchange for supporting his run for County Superior Court Judge in the June 2014 county elections, Buenaventura pledged his support to Canepa against Mike Guingona. That’s politics. If Canepa is elected to the San Mateo county board, then it will remain an all-white board in a county that is now 58 percent people of color.

There are two open seats in the City Council of Daly City and the two leading contenders are Filipino Americans, Glenn Sylvester and Juslyn Manalo. If they both win, there will be four Filipinos of the five members of City Council of Daly City, the largest of the 20 cities in San Mateo County. They will have the votes to change the city’s name to Adobo City. They may be able to change the name of a city park or school after Alice Bulos.

When Alice Bulos goes to Heaven and is welcomed by God, he will surely tell her: “You did not make me cry, Alice Bulos. I am so proud of you.”

We love you Alice.

(Vote Marjan Philhour for SF Supervisor D-1, Maggie de Guzman SF Supervisor D-11, Jim Navarro Mayor Union City, Mae Cendana Torlakson Assembly Contra Costa. Send comments to Rodel50@gmail.com or mail them to the Law Offices of Rodel Rodis at 2429 Ocean Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94127 or call 415.334.7800).