When PH was the only door open to fleeing Jews

The Nazis had robbed Lottie Hershfield of her childhood all too soon. She was just 7 years old when Germany, her place of birth, no longer felt like home.

Adolf Hitler’s regime held Jews like Hershfield and her family in the same regard as animals; at the park, benches carried signs that read “dogs and Jews not allowed.” The Nazis raided her family home, and all the frightened child could do was to tightly clutch her doll as a fierce German shepherd barked at her, as if ready to devour her.

Stateless and unwanted, Hershfield’s family and the Jewish community then learned that a country in the Pacific was ready to accept those seeking refuge. It was in the Philippines, a place largely unheard of, thousands of kilometers away from Europe, where she got her childhood back.

“When you saw how the doors were basically closed to all of us except the Philippines … the Filipino people are a very warm people, they’re a very friendly people,” Hershfield said in a preview of the documentary “An Open Door: Jewish Rescue in the Philippines.”

“We played sipa (kick). We learned Filipino songs, there were quite a few performances. Art was very important. Filipinos have very, very good voices,” said Hershfield, now 84 and settled in the United States.

Sanctuary for Jews

The Philippines became a sanctuary for at least 1,200 Jews rendered stateless by the racist Nazi regime, settling here between 1937 and 1941. They escaped just in time: Some 5 to 6 million Jews would be killed during the Holocaust in the years immediately after they fled.

“When the Jews had nowhere to go, President Manuel Quezon was the one who allowed them to come in. But when they came in, it was the Filipinos everywhere who made the Jews feel welcome,” said researcher Sharon Delmendo, who has devoted the last six years researching the arrival and settlement of Jews in the Philippines.

Delmendo has been on a mission to spread the word about the Philippines’ rescue of Jewish survivors, a part of the nation’s history overshadowed by the traditional textbook retelling marked by colonization, oppression and conflict.

“I think it’s very important for this to be known here. For one thing, it is because it’s a chapter of Philippine history in which the Filipinos are the heroes,” said Delmendo, a Filipino-American scholar based in New York who has extensively studied Philippine-US relations.

Humanitarian grounds

“It was President Quezon who did the sort of heavy lifting to get people here, but it was the Filipinos who made them welcome,” Delmendo said in an interview on Friday at Ayala Museum, where she delivered a lecture on the Jewish escape to the Philippines.

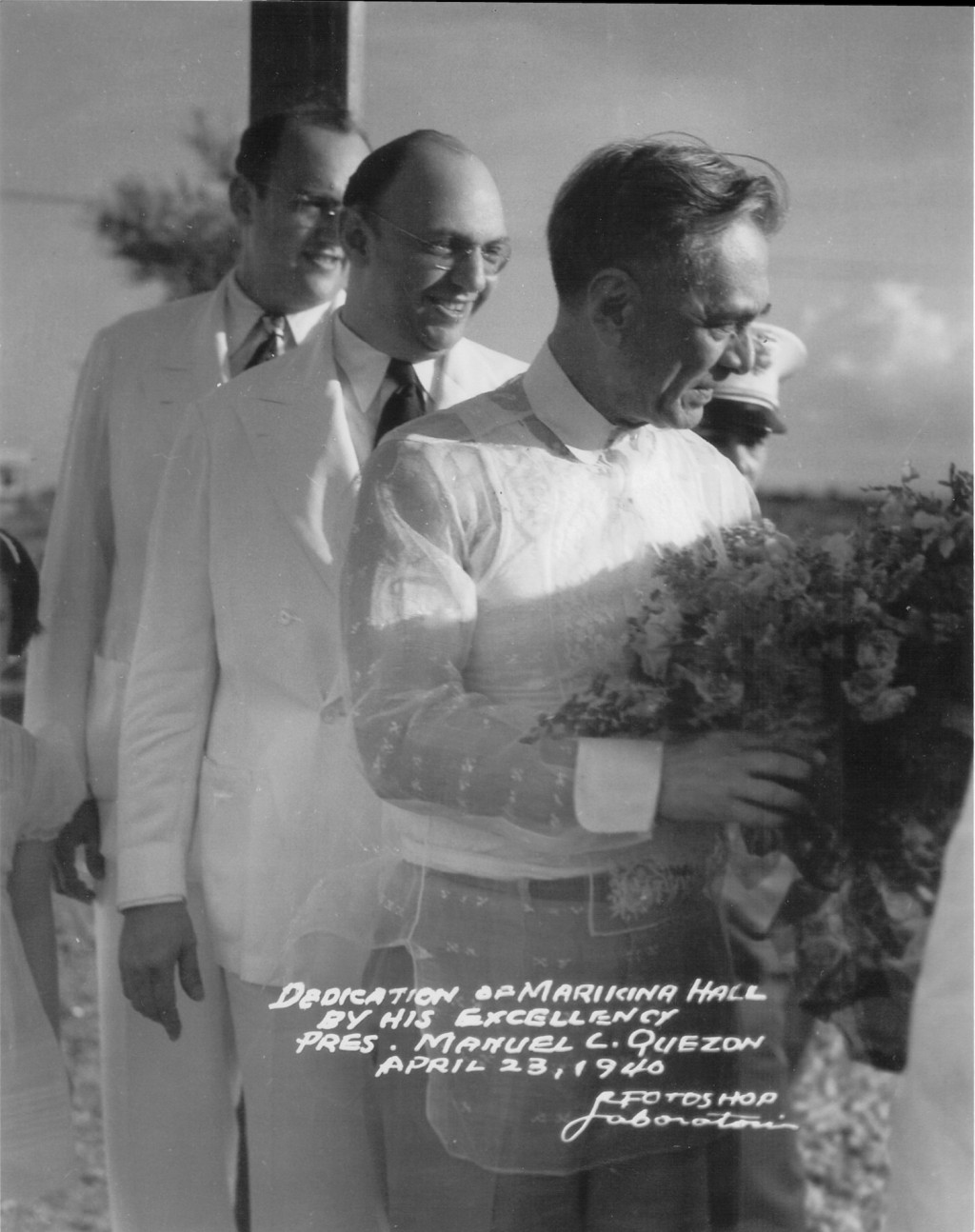

Quezon, who was President when the Philippines was part of the American Commonwealth, authorized the entry of Jewish refugees to the Philippines with the concurrence of US High Commissioner Paul McNutt toward the end of the 1930s.

READ: Philippines: A Jewish refuge from the Holocaust

“There’s no reason why Manuel Quezon had to let the Jews in. He had more than enough to worry him. He really did,” said Delmendo of the President who at the time was already sickly and advised to retire from public life.

“But basically, he said in presidential statements, this has to be done in broad humanitarian grounds. That was it,” she said.

On their own, Filipinos condemned the Nazi persecution of the Jews, gathering in a 2,000-strong crowd in an indignation rally in November 1938.

“So Filipinos just sort of spur of the moment rose up and said what the Nazis were doing was wrong, [that] ‘we could not condone this.’ And staging an indignation rally was not going to change anything, Hitler didn’t care, but still they felt strongly enough about it that they had to make a public demonstration,” Delmendo said.

When word got out that the Philippines was open, thousands of Jews petitioned the US state department to get visas to Manila, Delmendo said in her lecture.

In what became an ultimate expression of affinity with the Jews, Quezon donated his own property in Marikina for their resettlement. Once they arrived, the refugees became known as the “Manilaners”—the Jews who found a new home in the Philippines.

READ: Wartime haven for Jews in Marikina remembered

“Quezon made the refugees his next-door neighbors,” Delmendo said before a crowd that gathered officials from the Embassies of Israel and Austria, scholars, representatives from the Quezon family and other guests.

For the likes of Hershfield, finding a temporary home where the Jews could be free was a welcome turnaround.

“Lottie is so used to people being mean to her and being terrified, and then she comes to the Philippines and the kids are like ‘come join our game,’ and then giving them tastes of food, just treating them like human beings,” Delmendo said.

“And it was such a miracle of kindness and decency that even now they just sort of can’t believe,” she said.

Nearly eight decades later, the bond remains strong, with Jews still deeply indebted to Filipinos for embracing them at a time when no one else let them in, according to Delmendo.

“It’s very much utang na loob (debt of gratitude). It’s very, very interesting to see the cultural value of utang na loob that the Jews are expressing without even knowing it,” she said.

‘Heal the world’

This was evident when the Jewish community mobilized around the world to send help to the Philippines in the wake of Supertyphoon “Yolanda” (international name: Haiyan) in November 2013, she said.

“The part about Typhoon Haiyan and how the Jewish people really, really rose to the support of Filipinos and raised a terrific amount of money … the Manilaners are actually using the Jewish concept of ‘Tikkun Olam,’ or to heal or repair the world,” Delmendo said.

“So it’s very interesting to me, this cross-fertilization of Jews learning utang na loob and Filipinos learning Tikkun Olam. We’re learning the best cultural values from each other and using them to help each other,” she said.

For Israel Ambassador to the Philippines Effie Ben Matityau, the Philippines’ rescue of fleeing Jews is “one of the most beautiful chapters of Philippine history.”

“It was a great moral victory. That decision of President Manuel Quezon, it was open-door policy coupled with open-heart policy,” said the envoy in his remarks at the lecture.

“[B]etween the rise and fall of Nazi Germany, the world faced its darkest days of history. This is one of the most critical chapters of moral collapse in history. What’s so unique is the moral victory of a nation (the Philippines) without pretensions. No megalomania in this part of the world,” Matityau said.

More than the number of refugees saved, there are the lives of the thousands of their descendants made possible by one nation’s act of unconditional humanity.

“These are things of which the Filipinos can be proud and I think it does show that the Filipino tradition of hospitality is more meaningful than just merienda, and it did make a difference,” said Delmendo.

“There are over 8,000 descendants of the Manilaners, and these are people who would probably not be alive if those people (refugees) had not survived,” she said.

Delmendo’s lecture on Friday was the culmination of a series of talks on the Jewish rescue that also brought her to San Beda College in Alabang, Meridian International College in Taguig City and University of the Cordilleras.

She is working with documentary filmmaker Noel Izon to complete a full-length film that comprehensively documents the Jewish rescue, gathering funds to complete target shoots in the Philippines and Israel.

Delmendo, a professor at St. John Fisher College in Rochester, New York, is also working on a book about the still largely untold part of Philippine history, gathering documents from archives and libraries in the Philippines and the United States, and interviewing surviving Manilaners and their descendants. TVJ

RELATED STORIES

Jews honor Manuel L. Quezon on his 134th birthday