Japan volunteer keeps coming back

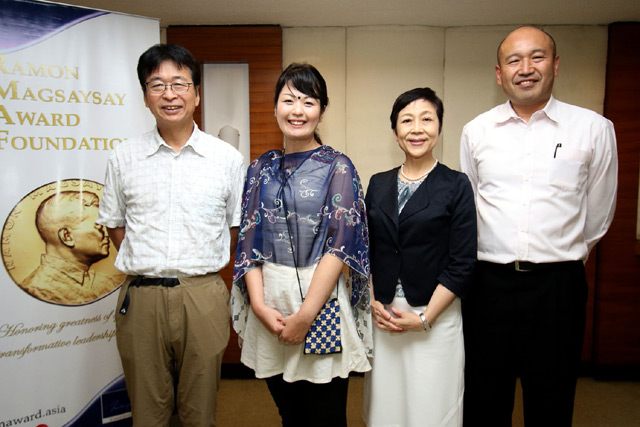

Members of Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers, a Ramon Magsaysay Awardee, pose during an interview in Manila.

It’s been 30 years since Kenichi Kubota worked as a Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteer (JOCV) in the Philippines, but he still finds himself returning to the country every year.

Aside from seeing friends that he made in Manila in 1980, Kubota, now 66, comes back to offer a helping hand to Filipino teachers.

“My relationship with this country never ended, it continued. I think of the Philippines as my second mother country, I have many friends here,” Kubota said in an interview.

He was one of more than 1,600 JOCV volunteers dispatched to the Philippines by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (Jica) since the program began in 1965.

Jica’s JOCV program is one of this year’s Ramon Magsaysay awardees.

The volunteers were cited for their “idealism and spirit of service in advancing the lives of communities other than their own,” showing that “it is when people live, work and think together that they lay the true foundation for peace and international solidarity.”

Jica’s volunteer program is part of Japan’s technical cooperation activities under its Official Development Assistance to developing economies.

More than 40,000 volunteers, aged 20 to 39, have been dispatched to 88 countries since 1965, with the volunteers staying for two years to help and interact with the local community.

Kenzo Iwakami, the executive adviser to the director general, said JOCV’s major areas of cooperation in the Philippines were agriculture, social welfare, education, health and disaster management.

“I think the Philippines is the second largest country in terms of accepting JOCV volunteers. Since the JOCV’s foundation, we have dispatched over 1,600 volunteers to Luzon, the Visayas and Mindanao,” he said.

One of the former volunteers was Kubota, now a professor of informatics at Kansai University in Osaka.

Two years after his stint in the Philippines, he married his girlfriend, Mayumi, a fellow JOCV volunteer who was dispatched to Ghana in Africa.

Kubota was assigned as a science teacher specializing in physics at Technological University of the Philippines (TUP) in 1980, training Filipino teachers for two years to promote science education.

He still treasures his Filipino friends, mostly based in Metro Manila and Bulacan province, from those days, visiting them whenever he comes to the Philippines.

Kubota and his students are part of a proposed project to meet education officials in Bulacan and help teachers prepare for the K-12 program to be implemented in Philippine schools.

“I come to the Philippines every year with my students to bring them to many places. I always visit my Japanese friend’s orphanage in Mindanao. It’s good for Japanese students to understand that collaboration with the Filipino people,” he said.

He recalled that during his first few months in the Philippines 30 years ago, he was lonely, knowing nothing about Filipino culture. He was unable to speak English well and even fell sick.

His Filipino counterpart, a female science teacher at TUP, was antagonistic toward him, telling him that she knew everything and that Kubota did not have to teach her anything.

“I think she was very much scared because of my existence. You know she had a position, she was afraid if I came to that university, I might take her position away,” he said.

The teacher eventually had a change of heart after seeing Kubota’s sincere efforts to get to know the other Filipino teachers, bonding with them over snacks or drinks.

“Gradually we became familiar with each other. Sometimes I visited her house to meet the parents. She became more open-minded in the end,” he said.

Building trust

Kubota stressed the importance of building trust between JOCV volunteers and the community they are helping, as goals cannot be achieved without mutual trust and collaboration.

“After half a year, we set up the teacher training sessions together. Once we got to know each other, things moved very quickly and we expanded to outside the university, inviting people to study with us,” he said.

Rina Tanaka, 32, a nurse and teacher at Naragakuen University in Nara, Japan, agreed, saying the most important lesson she learned in Bangladesh was trusting people.

“I learned how to trust people. But without trusting my colleagues, nothing can be started, that’s what I learned,” she said through an interpreter.

Tanaka was assigned to a rural area in the northern part of Bangladesh in 2012, where filariasis, an infectious tropical disease caused by parasitic round worms, was common.

Part of her duties was to monitor and deal with the spread of filariasis in the villages under her care, working with local health workers who were initially skeptical about her.

She went around the villages to check the health situation and report it to her boss, eventually winning the confidence of the local health workers as she interacted with them.

Tanaka, who initially did not understand the local culture, made an effort to have tea and share meals with the health workers, eventually learning that the locals were antagonistic toward health workers.

“Then the village workers started to think that I was their colleague. It took me one year to reach that point,” she said.

Learning from locals

As a newly assigned volunteer in Bangladesh, she described herself as a baby who knew nothing, but the local health workers took her under their wing and taught her the culture and the language.

“They really helped me. They didn’t give up on educating me, so I didn’t give up on them,” she said.

In her visits to the villages, she saw the poor public health situation of the locals, who often suffered from filariasis, polio, diarrhea and other parasitic infections.

At first, the health workers did not want to help her take care of the patients because they were not paid enough, but there was a male health worker there who was different from the rest and he began to help her.

“He said, ‘Rina is here to help us and this is our village, so there is no reason not to collaborate with her.’ He helped me all the way when I couldn’t speak Bengali,” Tanaka said.

The health worker who cooperated with her did not get any financial reward for his work, but continued to help the locals fight filariasis.

Jica vice president Kae Yanagisawa noted that in recent years, more women like Tanaka are signing up to volunteer in developing countries.

Since 1998, women have outnumbered male JOCV volunteers. More than 60 percent of the current volunteers are women.

“It turned out that women are more open-minded. Another reason is that it’s still more difficult for women to get decent jobs in Japan,” she said.

In the past, she said, Japanese women were pressured to get married in their 20s and that back then, it was unthinkable for women to work abroad, alone and away from home.

But since the 1990s, this social pressure decreased and Japanese women became more adventurous.

“Men are more conservative and are usually seeking a stable job, so being a volunteer is kind of risky,” Kubota said.

Yanagisawa added that JOCV is an avenue for young Japanese people to be exposed to different cultures and values, teaching them to respect and accept diversity.

“Without understanding diversity, we cannot build a healthy society. If you stay only in Japan, there’s limited chances to be exposed to other cultures, so JOCV is a very good way of exposing young people to different cultures,” she said.

The Jica vice president noted that JOCV volunteers usually leave Japan thinking that they would help the poor in other countries, but come back enriched by the rare experience.

“When volunteers come back home, they submit a report. Almost all volunteers say, ‘I wanted to help the people, but in the end I learned that I was helped by the people,’” Yanagisawa said.

Iwakami said volunteers realized that they, too, were supported by the locals they thought they were helping.

“I’d like to emphasize that volunteer work is not a one-sided activity. It’s mutual learning process and equal partnership,” he said.

For volunteers like Kubota and Tanaka, their JOCV stint might be long over, but the fire of volunteerism is still ablaze in their hearts.

Giving back

Tanaka now wants to give back what she learned in Bangladesh by teaching at a nursing college in Japan to share her experience with students.

“Given the chance, I want to volunteer for JOCV again, but my current goal is to give back what I learned in Bangladesh to Japanese community and society,” she said.

For Kubota, being a JOCV volunteer set him on the path of volunteerism even in his later years, returning to the Philippines to work with Filipino teachers.

“I believe that JOCV is the first step in being a volunteer. After I experienced being in JOCV, I realized that I could do volunteer activities even after I finished it,” he said.