In The Know: Hiroo Onoda

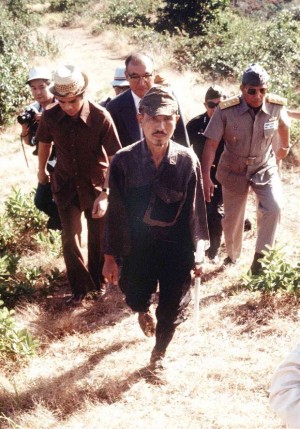

30 YEARS IN MINDORO JUNGLE Japanese straggler Hiroo Onoda (center) walks from a jungle on Lubang Island to surrender. Until then, he had not known World War II had ended. In this picture taken on March 11, 1974, he is flanked by then President Ferdinand Marcos’ Public Information Minister Kit Tatad (left) and Maj. Gen. Jose Rancudo. Behind is Japanese Ambassador Toshio Urabe. AFP

The son of a strict schoolteacher, Hiroo Onoda was working at a Japanese trading firm in Shanghai when he was conscripted into the military in 1942.

Trained as an intelligence officer, he was sent in December 1944 to Lubang Island off Mindoro province with orders to spy on the US military.

When the American forces landed in Lubang in 1945, Onoda and his companions were cut off from their unit and went into hiding.

While in hiding, Onoda kept a calendar, using the moon as his guide. Later, it turned out that he was just six days off the real calendar.

He was the last of several dozen so-called holdouts scattered around Asia, men who symbolized the astonishing perseverance of those called upon to fight for their emperor.

Article continues after this advertisementTheir existence became widely known in 1950, when one of their number emerged and returned to Japan.

Article continues after this advertisementIn 1972, Onoda’s last comrade was fatally shot in a gunfight with local farmers. He was left alone.

Two years later, a young adventurer named Norio Suzuki arrived on Lubang with the self-assigned mission of bringing Onoda out of the jungle.

Suzuki made camp in lonely clearings, allowing himself to be seen, and waited. One night, Onoda approached the startled student and allowed to be photographed. He said he could not leave until ordered.

Suzuki returned to Japan and contacted the government, which located Onoda’s superior, Maj. Yoshimi Taniguchi.

On March 10, 1974—nine days before his 52nd birthday—Onoda donned his carefully preserved Imperial Army uniform, complete with cap and sword, and stepped out of the jungle to formally receive his long-awaited order from his superior to surrender.

Asked at a press conference what he had been thinking about for the three decades, he told reporters: “Carrying out my orders.”

“I don’t consider those 30 years a waste of time,” Onoda said in another interview. “Without that experience, I wouldn’t have my life today.”

Onoda’s return to Japan was not easy in the beginning. His initial feelings of joy at his homecoming were replaced by a growing feeling of emptiness.

He moved to Brazil, where he bought a ranch and acquired 1,800 head of cattle. But he didn’t want to cut his ties with Japan. He married a Japanese woman and, in 1992, became the director of a children’s nature camp in northern Japan.

Until recently, Onoda had been active in speaking engagements across Japan and in 2013 appeared on national broadcaster NHK.

“I lived through an era called a war. What people say varies from era to era,” he told NHK. “I think we should not be swayed by the climate of the time, but think calmly,” he said. Inquirer Research with reports from AP and AFP

Source: Inquirer Archives

(Editor’s Note: Inquirer senior editors Fernando “Boy” del Mundo and Ruben Alabastro covered the surrender of Onoda on Lubang Island for their wire agencies in 1974.)

RELATED STORY: