Why Filipino Americans say Pilipino, not Filipino

SAN FRANCISCO — There’s an interesting side note to the ‘Filipinas’ vs ‘Pilipinas’ controversy. A similar debate, this time over whether it should be ‘Filipino’ or ‘Pilipino,’ also erupted decades ago — in America.

And those who pushed for ‘Pilipino’ won.

That’s why on many college campuses, especially in California, you’ll find groups like the Pilipino American Collegiate Endeavor, or PACE, at San Francisco State University; the Pilipino American Alliance at UC Berkeley; and the Pilipino American Student Union at Stanford University.

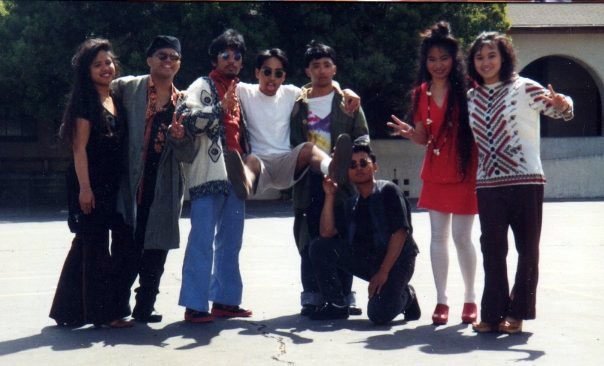

Members of the Pilipino American Collegiate Endeavor cast of the San Francisco State University student group’s Pilipino Cultural Night show in 1992. PHOTO/Elrik Jundis

And that’s why we have the phenomenon called Pilipino Cultural Night, better known as PCN.

That’s the yearly spring ritual on many US college campuses when hundreds of Filipino students hold musical extravaganzas, complete with traditional Filipino dances, hip-hop numbers and political skits, to celebrate Filipino (or Pilipino) culture.

The use of ‘Pilipino,’ as my friend and the academic Theo Gonzalves, associate professor and department chair of the American Studies Department at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, explains, was both an act of defiance and a choice.

Yes, it was partly based on the debate of whether there is or isn’t an ‘F’ in the Filipino alphabet.

But for Filipino Americans, it was a way of choosing, affirming and celebrating their Filipinoness, or Pilipinoness.

After all, the Filipino Americans argued, one can deconstruct ‘Pilipino’ into ‘pili,’ or ‘to choose,’ and ‘pino,’ or ‘fine.’

In other words, “a fine choice,” Theo says. “You see where this is going. Black is Beautiful and all that.”

“Black is Beautiful” is the famous African American slogan in the 1960s when blacks and other minorities asserted their rights to define their own identities and to tell their own histories.

“Just about everyone was interested in re-naming themselves,” Theo continues. “This reflected the larger process of decolonization that had been taking place throughout Africa, Asia, and the Americas since the 1950s.”

“At one point during this mid-century period of decolonization, the majority of the world’s population was in open revolt in some form or another, to European hegemony. And finding your way to a supposedly post-colonial world would involve thinking about yourself in new ways — new fashion, hairstyles, ideas about homelands, languages, and names.”

These new ways sometimes involved exploring and embracing the old.

Many Filipino Americans studied the old Tagalog script called Baybayin. Some of them even tattooed their names in the ancient text on their bodies. Others studied escrima and the kulintang.

A generation of Filipino Americans also was shaped by events in the homeland. Many were part of the fight against the Marcos dictatorship, an experience that propelled some to careers in public service and politics.

It was not always an easy or fruitful quest. I’ve heard stories of Filipino Americans who eventually grew tired of or who outgrew this passion for everything Filipino. Other felt discouraged after being rejected by Filipinos in the Philippines.

But others pushed on.

And while it may not be something that’s easily recognizable to or accepted by many Filipinos in the Philippines, Filipino American culture has thrived.

And it had little to do with any rigid rules on how Filipino Americans refer to themselves.

I myself still stick to saying Filipino when writing in English, and Pilipino, in Pilipino. Theo Gonzalves, who studied Filipino American culture for decades, also suggests that labels, in the long run, aren’t the most important factor in the Filipino American story.

“When I started to learn about that larger frame of decolonization, I welcomed the switch from F to P, especially in writing. As for self-identification, I never made any hard rules. … I don’t begrudge anyone the way they choose to identify themselves, whether Pinay, Pinoy, Pin@y, Pilipino America, Filipino/American, American Filipino…. In writing, I just prefer the rather generic and boring, “Filipino American.”

“More than anything else about this topic,” he said, “I’ve appreciated the historical aspect of choosing to rename yourself when the time is right.”

In fact, there are important lessons from the Filipino American experience when it comes to labels and identity. After all, Filipinos in America coined what’s become one of the most enduring labels we’ve embraced as a people: Pinoy and Pinay.

As historian Dawn Mabalon writes in her engaging new book “Little Manila Is in the Heart, “the terms ‘Pinoy’ and ‘Pinay’ were coined by Filipinos, mostly farm workers and factory workers, who moved to the US in the first half of the 20th Century.

Later, many of the snooty, middle class Filipino newcomers who arrived in the 1960s dismissed the label as lowbrow, or bakya.

But decades later, we all use them.

Visit and like the Kuwento page on Facebook at www.facebook.com/boyingpimentel

On Twitter @boyingpimentel