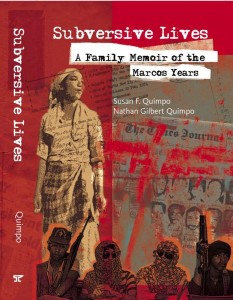

The memoir of a family’s struggles during the Marcos regime has drama, action, intrigue, faith and religion, heroism and betrayal. It even has elements of a thriller, Jason Bourne-style.

Most important of all, “Subversive Lives” is about claiming and owning the stories of heroism and struggle of Filipinos who gave up everything to save a nation from a brutal dictatorship.

It’s a courageous book. Mainly because many people will hate it. It will draw sneers, even outright attacks, from some influential players and forces.

The military and allies of the late dictator won’t be happy with it for the book exposes them as ruthless torturers and fascists.

The Opus Dei will condemn it for painting the religious order as an elitist cult.

The underground left will attack it for painting a mixed portrait of the UG movement – one of brilliant and committed young Filipinos willing to sacrifice everything to build a more equitable society, but which is led by paranoid leaders blinded by dogma, with shocking capacity for ruthless violence.

What I’m most intrigued, even excited, about is how this book will be received by young Filipinos.

For the book, in many ways, is about youth.

It’s about their idealism and rebelliousness, their passionate desire for change and their willingness to sacrifice everything for what they believe to be a just cause.

The narrative of the rebellious, subversive youth has long been part of Philippine and world history. It’s been explored in works of literature, from Les Miserables to Dekada ‘70. It was the force behind important historical events, from the anti-Vietnam War protests, the First Quarter Storm, to Tiananmen and even today’s Occupy Wall Street protests.

It can be romantic and exhilarating, at times even leading to meaningful change.

It can also be frightening. For that youthful passion can at times go awry causing young people to fall prey to false prophets or to encounter forces whose capacity for cruelty and violence they underestimated.

In Subversive Lives, we understand a little better the youth rebellion that confronted the Marcos tyranny.

Ishmael and Esperenza Quimpo had 10 children. Most of them became activists, eventually joining the underground left. That meant giving up their relatively comfortable lives and promising future.

Two of them died as a result of that commitment.

Those of us who lived through the times the Quimpos recall in this book would identify with the fire that they and other young Filipinos felt in their hearts during a dark chapter in our history.

Norman Quimpo, the first activist in the family, recalls, “In those times, there was a little a parent could do to prevent a determined teenager from joining demonstrations or signing up for of the radical organizations that sprouted like mushrooms after the First Quarter Storm. After all, it was something romantic to be a student activist.”

Perhaps because I am now also a father, I found myself also feeling the pain their parents endured as a result of their children’s activism.

Some of the most moving parts of the book are when the Quimpos recall the torment of their father and mother as the activists in the family took the road less travelled.

There was Nathan, a brilliant student who could have chosen a safe, lucrative career in business or even politics. It was a path his parents also hoped he and their children would take. Instead, Nathan and some of his siblings chose the UG life, which also meant imprisonment and torture. He was in military custody when he visited his dying father. The heartbreaking scene is recalled in the book.

“Even in his dying days Dad was not about to show his emotions,” he writes. “Not even when he and Mom had worked hard through most of their lives to send their children to the best of schools, wanting to get us all through college, hoping that we would all become successful doctors, lawyers, engineers and bankers one day. And now he was seeing us in hiding, on the run, or behind barbed wire, either fugitives or prisoners.”

“What could I say to my dying, unhappy father about his shattered dreams? Sorry Dad we did not live up to your expectations? Sorry, it’s not your fault, but it’s not our fault either? That we were all victims of circumstances, or victims of an unjust social order and of a dictatorship?”

These were also questions of many young people from middle class families who were expected to take the safe path, but who instead chose a dangerous route to defy a tyrant.

One sibling, Emilie, took another road, one based on faith as defined by Opus Dei. But just as her siblings became disillusioned with the UG, she grew to reject a different form of dogmatism.

“I finally buckled under the crushing burden of vocational disillusionment and betrayal,” she writes. “Compared to my brother’s selfless and generous commitment to real and genuine causes in his very short life, my 14 years in Opus Dei where everything revolved around well-to-do and comfortably placed persons, seemed a meaningless farce and an absolute waste of time and resources.”

Not all the Quimpo siblings were initially convinced that it was a good idea to recall their experiences.

Lillian Quimpo wasn’t crazy about the idea, as the preface explains: “She feared the work would celebrate the ‘courageous, noble, romantic, and glorious’ sacrifice of activists, when all she could see was wasted lives. She cringed at the possibility of a Dickensian tear-jerker. Still, as the book grew in heft and she could read more of her siblings’ stories, Lillian eventually came around.”

And it was a good thing she did. It’s a good thing that the Quimpos decided to put together a book that honestly looks back at their incredible journey.

Certainly, there are those who would view the young UG activists who died in the fight against dictatorship as “wasted lives.”

But there’s another view.

For despite the violent, senseless dogmatism of the movement’s leaders, young Filipinos like Jun Quimpo, Edgar Jopson, Eman Lacaba and Lorena Barros helped create a new political culture, one that stresses a more intense focus on the needs of the weakest and poorest in society.

That culture has endured in many ways. It lives on in the vibrant network of non-governmental groups and activist organizations many of which sprang from the UG movement, which have elevated the public discourse on such issues as human rights, women’s rights and even the environment.

Which is why there should be more books like “Subversive Lives.” For it helps us better understand our recent past.

Even though telling these stories won’t always be easy.

I myself found that out. At 25, I wrote what I then thought was more or less the complete story of Edgar Jopson, perhaps the best known rebel of the First Quarter Storm who stunned society by joining the UG.

I realized I was wrong. It was an incomplete story, one that painted too flattering a portrait of the UG.

So at 42, 17 years after my first attempt, I tried again with “U.G. An Underground Tale,” published in 2006 by Anvil, also the publisher of “Subversive Lives.”

Some asked why I even bothered to revise the book.

The reason also speaks to why I think there should be more books like “Subversive Lives.”

These may be painful, heart-wrenching stories. But they should not be abandoned. These stories should not be left to those who would deny their true importance and meaning.

Not the military and forces of tyranny who would want to suppress them. Not the demagogues of the UG left who would distort or sanitize them to suit their narrow political agenda based on a twisted concept of the correct line.

These stories should be uncovered and preserved so young Filipinos can learn from them. So they can understand their need to rebel, to reject the system, to subvert the dominant paradigm, to seek a better society.

Also, so they can understand that they aren’t the only ones who feel that way. That in our past, many other young people also felt a burning desire to change the way things are in Philippine society.

And there are many things they can learn from what they went through.

On Twitter @KuwentoPimentel. On Facebook at www.facebook.com/benjamin.pimentel