Asean approach to Myanmar crisis has split the region, reveals new survey

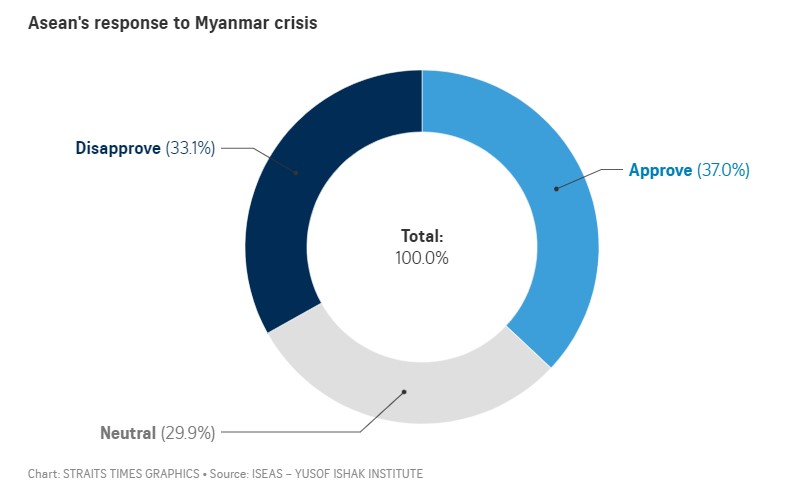

SINGAPORE – Asean’s response to the Myanmar crisis has divided public opinion in South-east Asia, with those who approve of its approach only slightly more than those in the opposing camp, who say it has not managed to resolve one of the most pressing challenges in the region.

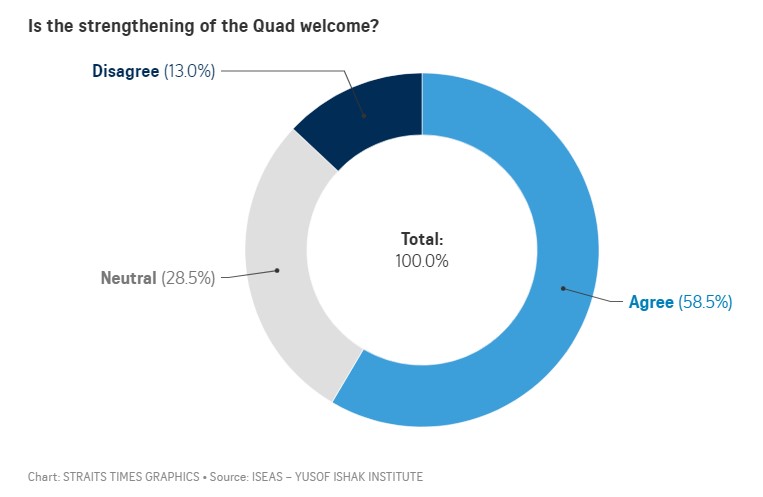

South-east Asia also appears to approve of the increasing stature of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and the new Aukus security arrangement that allows Australia to operate and construct nuclear-powered submarines amid perceptions that China’s presence in the region needs to be balanced.

The findings are from the annual State of South-east Asia survey released by the ISEAS -Yusof Ishak Institute on Wednesday (Feb 16). Now into its fourth edition, the survey conducted over the last two months of 2021 captured views from the region’s policymakers, academics, researchers, businessmen, media and civil society activists on key regional and geopolitical developments.

The release of the findings coincides with a meeting of Asean foreign ministers in Phnom Penh over Wednesday and Thursday (Feb 16-17) to address the crisis in Myanmar where a military coup ousted an elected government last February.

The survey showed that 37 per cent of the 1,677 respondents approved of Asean’s response to the crisis while around 33 per cent disapproved and 30 per cent remained neutral.

After Ms Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy was replaced by a State Administration Council headed by armed forces leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, Asean has pressed for a constructive dialogue among all parties to resolve the crisis, taking some bold steps while not abandoning its enshrined principle of non-interference.

At its annual leaders’ summit last year, Asean took the unprecedented action of barring Gen Min Aung Hlaing and reducing Myanmar to non-political representation at the talks. However, Asean has not managed to win meaningful concessions from the junta which continues to limit the bloc’s access to Aung San Suu Kyi or members of her deposed government.

The crisis has put Asean’s unity as well as its centrality to the test, noted the survey.

Of those who approved, 42.5 per cent felt that Asean had taken active steps to mediate in the crisis. Among those who disapproved, 45.5 per cent thought Asean was not responding fast enough to the escalating political and humanitarian crisis. The disapproval rang the loudest in Myanmar (78.8%), with the people in Thailand (39.3%) and Singapore (37%) giving the next most negative ratings.

Brunei was most approving of Asean’s response (58.5%) which the survey ascribed to the fact that the country had to handle the issue as it held the Asean chairmanship when the coup occurred. Indonesians were second most approving of Asean response (44.3%), perhaps reflective of Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi’s shuttle diplomacy in the early days of the crisis. The third-most approving was Singapore at 43.7%.

At a webinar to discuss the findings, Professor Chan Heng Chee, Singapore’s Ambassador-at-Large and Chairman of ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s Board of Trustees, noted the criticism that Asean had been slow.

She said: “On the humanitarian aspects, Asean can act faster. But could Asean have been harder? There are institutional and structural reasons why Asean cannot move as fast as some countries want to because we have a consensus approach. Our constitution does not allow us to suspend or expel the member state. Asean came up with the consensus principle because it makes 10 countries comfortable. Change that and I don’t know if we can keep the members together. I get that young people in Myanmar want us to move faster. But this is the only Asean we have, you deal with what you can.”

Quad gets thumbs-up, Aukus surfaces some unease

The survey also provided a glimpse of regional attitudes towards key security developments. Some 58.5 per cent of the respondents welcomed the strengthening of Quad and its potential for cooperation in areas such as vaccine security and climate change.

The loose grouping, through which the United States, Japan, Australia and India coordinate their response on security, economic, and health challenges in the Indo-Pacific, was formed after the Boxing Day tsunami in 2004 but lay largely dormant until its first leaders summit last year.

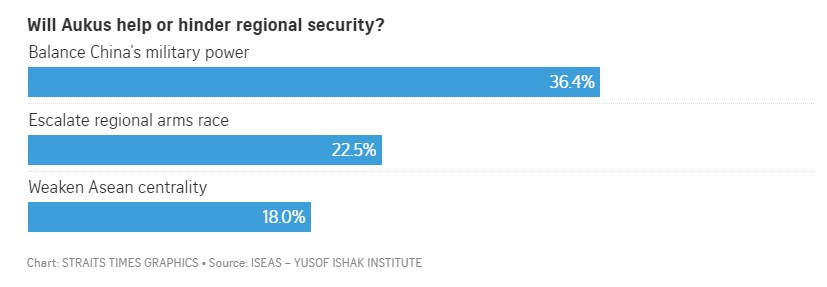

On regional security, 36.4 per cent of respondents felt that the Aukus arrangement between Australia, the United Kingdom and the US will help balance China’s growing military power. But pointing to the undercurrent of unease sparked off by the trilateral strategic alliance founded last September, 22.5 per cent felt that it will escalate the regional arms race. The pact allows Australia to operate and build nuclear-powered submarines. As many as 18 per cent said it would weaken Asean centrality, the organisation’s ability to call the shots in its own region.

Prof Evelyn Goh of the Australian National University said she was struck by the findings that the proportion of people who thought that Aukus would present another avenue of balancing China was higher than those who thought that this would exacerbate the arms race in the region. “It does reflect tendency in Asean to think in a diverse way, we tend to be open to different ideas of how to temper potential excesses of power in the region,” she said.

On fears that great power rivalry could erode Asean centrality, Prof Chan pointed out that the antidote lay in unity. “When Asean sticks together, the major powers change their language,” she noted. “When the Quad started, Asean had qualms about its containment of China. The language has changed, it’s now about delivering public goods, inclusive of coalitions and initiatives.”

Likewise, the White House has lately talked about delivering prosperity in its Indo-Pacific strategy after feedback that it was what the region most wanted. China, too, has been prevailed upon to temper its position reflecting the stance Asean took on South China Sea issues.

“Asean likes a Goldilocks policy, not too hot, not too cold, just right,” she said. “If it gets too hot, they want major power to retreat a bit. If it gets too cold, they want them to come in. It is about balancing China.

The discussion was moderated by ISEAS Director and CEO Choi Shing Kwok.

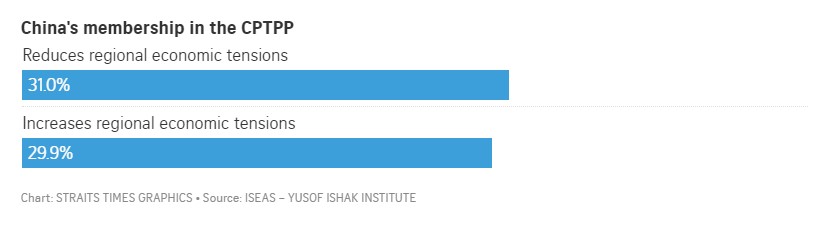

The respondents were also polled on a gamechanging development last year – China’s interest in joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a trade pact which the Biden administration has not joined after it was jettisoned by the Trump administration.

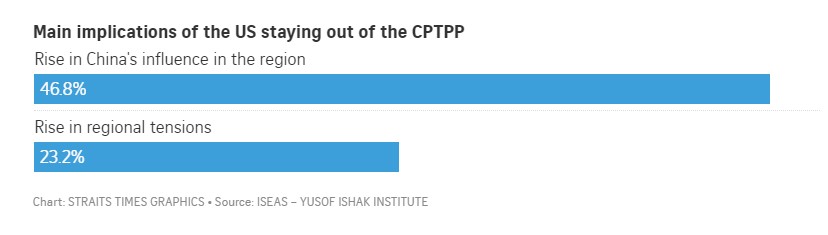

Some 31 per cent felt it would reduce economic tensions in the region and help to resolve the US-China trade war. But nearly 30 per cent disagreed. In the absence of the US, close to half (46.8%) are of the view that a rise in China’s influence will fill the void. Some 23.2 per cent are worried about the rise in regional tensions as the US shifts its focus of engagement to exclusive security pacts in the Indo-Pacific

Pandemic remains top concern, govt handling takes more flak

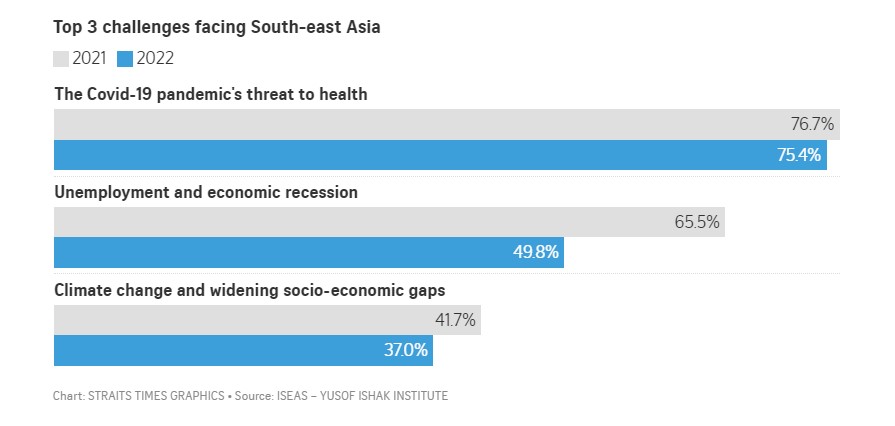

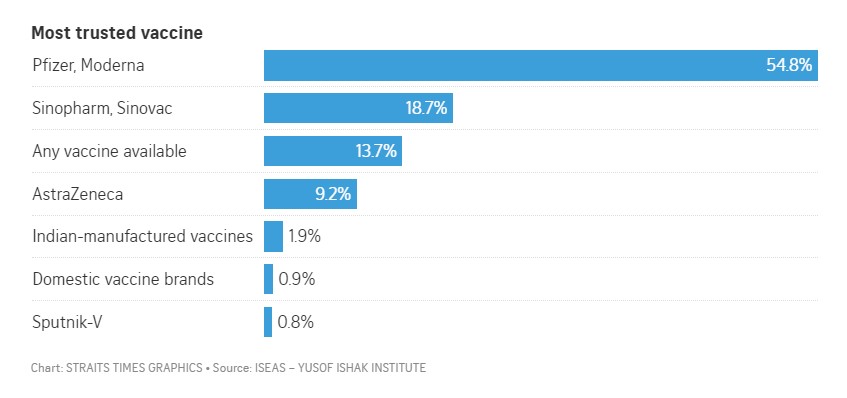

Overall, the most pressing concerns remain the pandemic’s threat to health (75.4%), followed by unemployment and economic recession (49.8%), and the impact of climate change (37.0%). Significantly, climate change overtook the third ranked challenge last year which was widening socio-economic gaps and rising income disparity. Terrorism continues to rank last at 12.5%.

Perhaps due to the Delta variant that wreaked havoc in the region in 2021, disapproval of regional governments’ handling of Covid-19 increased from 23.8% in 2021 to 30.6% in 2022.

Those who said that their governments performed very poorly more than doubled from 7.1% to 15.9%. And those who felt that their governments performed well or adequately dropped by 10 percentage points from 61.0% to 51.0%. Bruneians thought the highest of their government’s handling of the pandemic (98.1%), followed by Singaporeans (87.8%).

China remains most influential power in the region

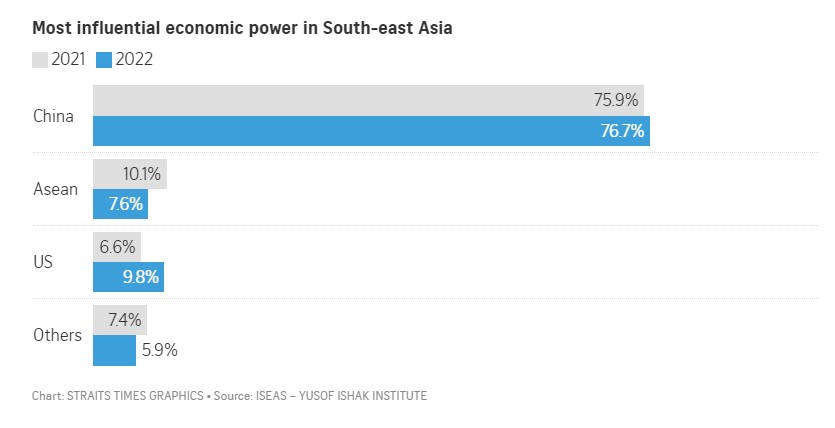

China is still perceived as the most influential economic power by 76.7% of the respondents, a consistent finding since the first survey in 2019. At a far distance behind are the US (9.8%, an increase from 6.6% in 2021) and Asean (7.6%).

China also remains the most influential political and strategic power in South-east Asia (54.4%), followed by the US (29.7%) and Asean (11.2%).

The largest group of the respondents (41.7%) continues to view China as a revisionist power that intends to turn South-east Asia into its sphere of influence. Nearly 14 per cent think the country is a status quo power and will continue to support the existing regional order, while those who see China as a benign and benevolent power stand at 7 percent.

Prof Zha Daojiong of Peking University said the findings were food for thought for how China conducts its foreign and economic policy. “It needs to be better explained domestically and overseas,” he said.

There was also notable approval for the Biden administration’s efforts to engage South-east Asia, with respondents rating the US the highest in championing free trade (US at 30.1% and China at 24.6%) and upholding the rules-based order (the US at 36.6%, Asean at 16.8% and China at 13.6%).

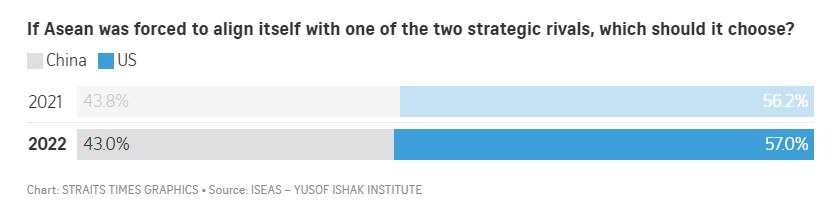

In response to the rivalry between the US and China, the preferred response is for Asean to stay united and build up resilience(46.1%). The idea of a proactive Asean is gaining ground, said the survey, compared to the traditional and more passive stance of not choosing sides between China and the US (26.6%).

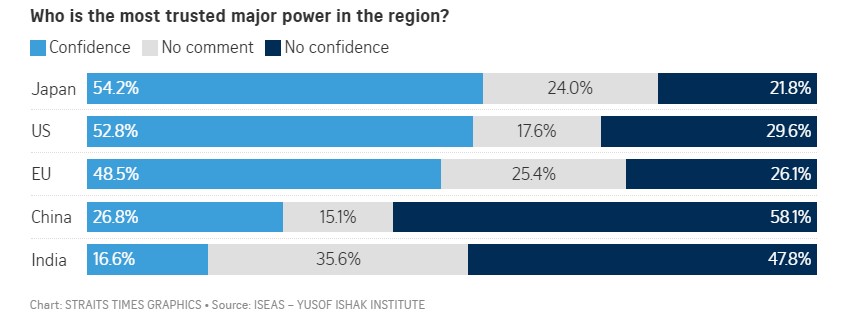

Also rising in popularity is for Asean to seek out “third parties” to hedge against the Sino-American rivalry (16.2%). The most popular in that role is the European Union (40.2%) and Japan (29.9%), with Australia a distant third (10.3%), followed by Britain (8.4%), South Korea (6.8%), and India (5.1%)

Although it suffered a drop in its ratings, Japan remains the most trusted major power, with 54.2% of the respondents expressing confidence in Japan to “do the right thing” to provide global public goods, followed by the US (52.8%), and the EU (48.5%).

Japan’s trust ranking was 68.2% last year but appears to have taken a hit after Covid-related restrictions curbed Tokyo’s engagement with the regional leaders, especially when viewed against Asean’s higher-level engagement with China, with President Xi Jinping making his first ever appearance at the Asean-China special commemorative summit.