Filipino workers endure more than fear of coronavirus in Hong Kong

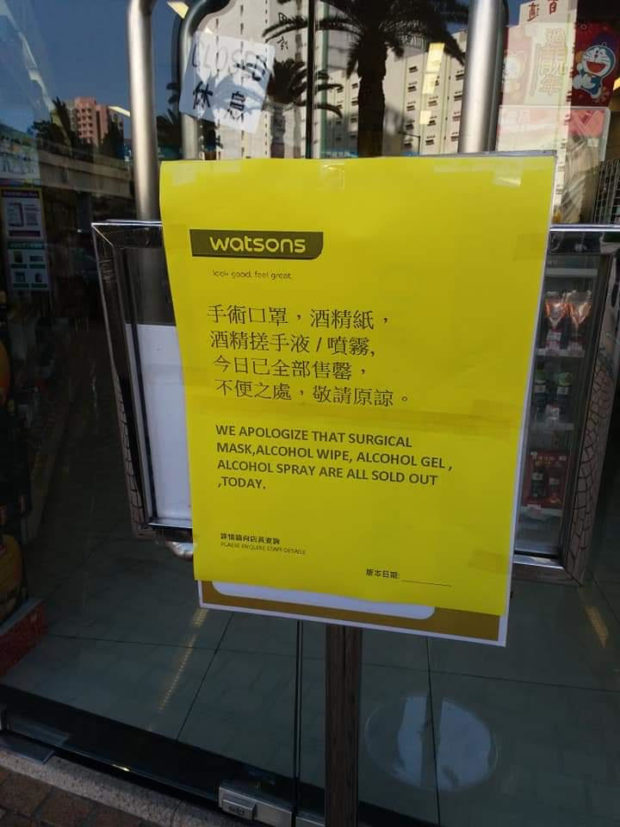

Notice posted outside a Watsons store in Hong Kong announcing there are no more masks and sanitizers. CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

MANILA, Philippines—The deadly novel coronavirus (nCoV) is coughing out horror stories from tens of thousands of Filipino workers, mostly domestic helpers, in Hong Kong who found themselves struggling with tough choices—to come home to unemployment or stick with Chinese employers driven by paranoia over the virus to treat their household workers worse.

Many Filipino household workers had already been laid off but can’t return home because of canceled flights, according to Lisa, a household employee who asked that her full name not be used, citing cases she was personally aware of.

The flight cancellations had also kept budget tourists, the type brought into Hong Kong by tour groups, from leaving, according to Lisa, citing local news and scenes at hotels and transport terminals. They’re stranded in Hong Kong with nearly nowhere to go as public places were emptied by the virus scare.

Many other Filipino household workers are being driven by fear of the virus to plan to cut short their employments to return home to the Philippines only for their plans to run into brick walls when they realize no flights were available.

Those who remained employed had to suffer a two-way paranoia in their bosses’ cramped apartments—their employers getting anxious if their Filipino workers had been infected and Filipino helpers becoming fearful that their Chinese sirs and ma’ams had the virus.

Article continues after this advertisementSmall space, big risk

In apartments that measure not more than 30 square meters, the chance of contracting nCoV was high. The virus’ transmission rate increases as space within which it moves decreases, according to experts.

Article continues after this advertisementAccording to Lisa, news had reached the OFW community in Hong Kong about a Filipino household employee who had been sent to quarantine because her employer tested positive for nCoV. The Filipino was a stay-in household worker.

Empty shelves at a Hong Kong grocery store tell story of panic after Hong Kong authorities announced the territory’s first novel coronavirus death. CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

The news circulated among Filipino workers, hammering one thought in their minds—the near certainty of getting seriously sick while far from home.

It didn’t help that the Hong Kong government seemed to vacillate about tougher measures to contain the virus, failing to ease the fear that was already driving many Filipino domestics in the Chinese territory to tears of despair, according to Lisa.

While experts said masks offer just a sense of security and could filter out only visible respiratory droplets of those infected, these still meant protection for Filipinos and made them feel safe, Lisa said.

As nCoV struck fear in the hearts of many Hong Kong residents, the mask became a symbol of two of the most prominent ways with which Filipino domestic workers are being treated in the Chinese territory—condescension and benign tolerance. These became more visible through the distribution of one of the most ubiquitous signs of fear over nCoV in Hong Kong and elsewhere—medical masks.

Masks were first to disappear from stores all over Hong Kong, in scenes that were repeated worldwide, including in the Philippines where, until now, no mask can be bought at pharmacies or drug stores. Empty shelves at grocery and drug stores and supermarkets told the story.

Use sparingly

The scale in which demand for masks unfolded in Hong Kong had prompted announcements by the territory’s leader, Carrie Lam, telling people not to wear masks unless they were in crowded places or in quarantine facilities to conserve whatever amount of masks was still available, according to Lisa.

Empty shelves at a Hong Kong grocery store tell story of panic after Hong Kong authorities announced the territory’s first novel coronavirus death. CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

As nCoV fear spread, employers sent out their Filipino helpers to fall in line at stores and hospitals for masks. Lisa recalled standing in line for three hours to get masks for her employer but none for her.

“It’s like we don’t deserve protection,” Lisa said in Filipino in messages sent through WhatsApp.

In a report of the Hong Kong newspaper The Sun of Hong Kong, Filipino domestics were seen staging a mini protest at a church holding up placards with a list of appeals to employers, among them to provide their workers with masks.

But being deprived of masks was just one of the symptoms of conditions turning bad for many Filipino household employees in Hong Kong as fear of nCoV spread. One of the things that the virus changed for the worse for the Filipino workers was the amount of work their bosses dumped on them.

In Lisa’s case, she said she had no complaint when she was being made to do nearly nonstop work in her boss’ apartment. The advent of nCoV made it double.

Now, Lisa said, she’s being made to apply bleach and disinfectant nearly every hour on surfaces, clothes, walls and everything that her boss believes could host the virus.

Killing good bacteria

At the rate she’s being made to disinfect the apartment, Lisa said she might be killing good bacteria, too. “What would now fight the bad bacteria if the good bacteria get killed, too,” she said in her WhatsApp message.

It doesn’t help that her female boss nags her all the time, Lisa said, telling her she’s no good.

She sent copies of messages being circulated among household workers in Hong Kong on a Facebook page called “OFWs in Hong Kong,” which featured travails of domestics who share their sob stories anonymously for fear of retaliation by their employers.

One worker said when fear of the virus struck, her bosses gave her instruction to spray them with alcohol at their apartment’s doorway before they enter. No problem, said the worker. But to remove their shoes from their feet, too, and disinfect these smacked of lowly treatment befitting a slave, the complaining domestic said.

One worker, a cousin of Lisa’s, contracted a fever and spent three days at a hospital. When doctors cleared her and found no trace of nCoV in her system, she returned to her employer’s apartment to report for work. The employer, however, refused to let her in and made her wait outside the apartment building. She sat on a staircase for eight hours, wearing a mask and her work shirt as the day wore on and the temperature dropped to 18 degrees Celsius.

The hand of a household worker appears swollen at a Hong Kong hospital where she was made to stay for an extended period by her employer who didn’t want her to return to work out of fear the Filipino helper had contracted novel coronavirus. CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

To prevent the spread of the virus, the Hong Kong government also targeted the weekly gatherings of Filipino household workers in their favorite places, ordering a halt to these assemblies which have become famous sights on Sundays, when the workers take their day off.

The order, said Lisa, presented a dilemma for both workers and employers. Workers who stay in their bosses’ apartments normally don’t have their own rooms so they’ll end up like loiterers in their employers’ living rooms, kitchen or dining rooms when they’re supposed to be out for the day. Their employers were also put in a quandary since their workers’ presence in their apartments on their day off would mean a paid workday that rattled some of the Filipinos’ stingy Chinese bosses.

Light of kindness

Amid the gloom and horror tales, however, shine some of the most touching acts of kindness that some Chinese employers show their Filipino household workers.

One worker, who returned to the Philippines on vacation, told of a story about her boss purchasing a more expensive ticket from Cathay Pacific when the worker, who already had a ticket to Hong Kong for Cebu Pacific, said flights were canceled from the Philippines to the Chinese territory.

The boss wasn’t aware that the flight cancellation applied to all airlines servicing the Philippines-Hong Kong route or probably had hoped that the cancellations applied only to Philippine airlines.

“My boss really wants me to come back to her,” said the worker in a message shared in the community of Filipino workers in Hong Kong.

The boss didn’t want the worker to miss her salary so she offered to pay the worker’s full salary until Feb. 7, when hopefully she could return to work.

After Feb. 7 and the worker’s still stuck in the Philippines, her employer offered to pay half her monthly salary until she’s able to return to Hong Kong to work again with her full salary restored.

“You think this is OK?” read a message sent by the employer to her worker. “Hope you can come back soon,” the employer wrote. “We all miss you so much,” continued the message to the worker with a tearful emoji.

The minimum wage for household helpers in Hong Kong is around P30,000 a month plus at least P6,000 in food allowance if employers don’t provide food to their domestic helpers.

Home alone

Another story that could be confusing over whether it was an act of kindness or paranoia involved a household helper who was reporting for work following a bout with fever and cough which were found unrelated to nCoV.

The helper returned to her employer’s apartment but the employer refused to come home and allowed her helper to have the apartment all by herself until they were both sure the helper had not been infected by nCoV. The episode was shared by other domestics in Hong Kong using the hashtag discrimination.

According to a report in INQUIRER.net, Hong Kong had shut its land and sea border crossings with mainland China after medical workers went on strike to demand border closure.

This followed Hong Kong’s first nCoV casualty, a man who had been to Wuhan, a highly developed city in the Chinese province of Hubei which is now the epicenter of the virus.

The Centre for Health Protection of Hong Kong’s Department of Health had a long list of to-dos in the fight against nCoV. Prominent among these was the wearing of surgical masks, the same item that Filipino household helpers had little or no access to.

Among Filipino workers, Lisa said there’s just one question lingering in their minds—“When will this nCoV crisis end?”

“It’s adding to the stress that OFWs feel with their employers,” she said.

“But while it’s tough, there’s no choice but to endure,” Lisa said. “For family. For those back in the Philippines.”

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here.

What you need to know about Coronavirus.

For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link.