Will next UN rights chief be gentler?

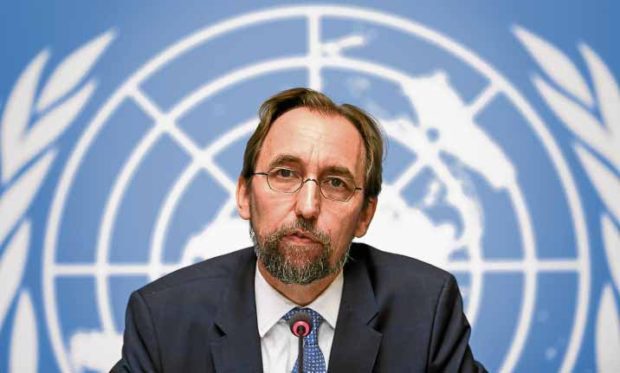

Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein —AFP

GENEVA — He suggested the Philippines’ President Rodrigo Duterte needed a “psychiatric evaluation,” called Hungary’s prime minister a racist, and accused US President Donald Trump of driving humanity off a mountain.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, has acknowledged that his unvarnished criticism of world leaders has made it impossible for him to secure a second term.

“I have irritated, I think, all governments over the course of [my] four years,” Zeid, a member of Jordan’s royal family, told The British Broadcasting Corp. at the weekend.

Among the leaders he had pricked in defense of human rights were Trump and Hungary’s Viktor Orban, for their anti-immigrant moves, and the Philippine President, for threatening UN special rapporteurs with arrest if they came to the Philippines to investigate the thousands of killings in his brutal war on drugs and listing one of them as a terrorist for defending the rights of indigenous peoples on the southern island of Mindanao.

Change of tone

As the deadline approaches to replace Zeid, one candidate vying for the job has argued that with the UN human rights system facing unprecedented threats, the rights chief’s office needs a change in tone.

“The next high commissioner must understand that defending human rights is not about attacking governments, it is not an exercise aiming to attribute blame or fault,” Nils Melzer, the current UN special rapporteur on torture, wrote in a letter announcing his bid to succeed Zeid.

“There is no point in winning perceived moral superiority at the price of mutual loss of respect, influence and understanding,” added Melzer, a Swiss national.

Melzer told Agence France-Presse (AFP) that even though he was probably not a front-runner for the job, he tweeted his application letter to trigger a necessary debate.

He expressed “tremendous respect” for Zeid but said that “antagonizing” political leaders did not work.

“We are on the brink of the whole system rights system disintegrating,” Melzer said. “If we want to avoid a global shipwreck, we will have to find a common language.”

Anyone interested in the long-term survival of the UN human rights system “will realize that the high commissioner can’t be an activist,” he said.

‘A bed of nails’

Zeid told BBC that other UN departments sometimes viewed the rights office as “sanctimonious” and that at points during his tenure, he was encouraged to use “alternative vocabulary” when denouncing abuses.

But tensions between the high commissioner for human rights and the rest of the UN system are hardly unique to Zeid, as the job typically requires harsh criticism of governments that other agencies are lobbying for resources and cooperation.

Edward Mortimer, a former UN communications director, called the rights chief post “a bed of nails,” in an article for the United Nations Association of the United Kingdom (UNA-UK), an NGO tracking the selection process.

Some argue that Zeid’s approach to the role denouncing the individuals personally responsible for the grave abuses is the only viable strategy.

“This is really what the job is all about,” Louis Charbonneau, the UN director at Human Rights Watch, told AFP.

“It is not about tiptoeing around. It is using the bully pulpit,” Charbonneau said.

Former Irish President Mary Robinson, who served as UN rights chief from 1997 to 2002, told UNA-UK that “if you become too popular in that job, remember, you are not doing a good job.”

The contenders

Zeid’s term expires this month. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres formally posted the vacancy in June and reportedly began interviews in July.

Few details about the selection process have been released, but multiple UN officials and diplomats have said that former Chilean President Michelle Bachelet was approached although she reportedly turned the job down initially.

Guterres is widely believed to prefer a woman for the role.

For activists, a priority is establishing whether Guterres is looking for someone who aligns with Melzer’s vision of a high commissioner who condemns abuses without denouncing leaders.

As Charbonneau noted, Guterres “has come under criticism for not being as outspoken as groups like ours would like on human rights.”

With Trump cutting support and China as well as Russia consistently undermining human rights criticisms from the United Nations, activists worry that Guterres may want someone more conciliatory toward the three most powerful permanent Security Council members.

Zeid told the BBC that even a partial bow to such states would be a mistake.

“Governments can defend themselves,” he said. “I am not there to defend them. I am there to defend their people who have been discriminated against.”