San Francisco—Kenyan environmentalist Wangari Maathai, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004, died on Sunday. She was one of the most admired activists in Africa and the world.

As far as I know, she and Filipino activist Lean Alejandro never met. But the two found themselves linked a few years ago.

In fact, they still are. Arms-linked, to be precise, in a classic ‘kapit-bisig’ pose known to activists worldwide.

On Masonic Avenue, in a corner of San Francisco, Lean and Maathai stand together as symbols of the fight against repression, and for social justice.

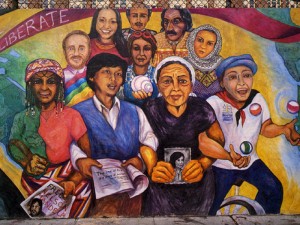

Their images are part of a mural called “Educate to Liberate.” It shows Lean with Maathai on his right. On Lean’s other side is a Salvadoran mother of a desaparecido, those who were made to disappear by right-wing forces in the Central American nation.

On the mural are other symbols of courage: the American engineer Benjamin Linder who was killed by U.S.-backed Contras in Nicaragua; Native American activist Leonard Peltier and Puerto Rican nationalist Pedro Albizu Campos.

Around their portraits is a tapestry of political images depicting a hodgepodge of causes — from the fight against global hunger and colonialism, to the battle for the rights of minorities and the elderly.

Beneath Lean’s portrait is the quote that made him famous: “The place of honor is the line of fire.”

Lean Alejandro, to those who are unfamiliar with his story of courage, was assassinated by right-wing elements on Sept. 19, 1987. He was 27. He had spent his short, but brilliant, life fighting the despotic regime of Ferdinand Marcos.

Also on the mural is a leaflet which Maathai is shown handing to the viewer on the street.

On the page are her words: “I would like to call on young people to commit themselves to activities that contribute toward achieving their long-term dreams. They have the energy and creativity to shape a sustainable future. To the young people I say, you are a gift to your communities and indeed the world. You are our hope and our future.”

The story of the mural is itself inspiring. And enlightening.

The Haight Ashbury Muralists led by Miranda Bergman and Jane Norling had just started painting it in the late 1980s when Lean was brutally shot dead in Quezon City.

Lean had visited San Francisco several times in the 1980s, and was respected and admired by the local U.S. activists.

As Norling told me four years ago, “Moved by Lean’s dedication to justice and enraged by his death, we immediately brought him into our mural for the people of San Francisco to know and honor.”

It was then a different portrait. In the 1988 version of the mural, Lean was standing arms-linked with another activist, Winnie Mandela of South Africa.

The mural was revised five years ago. The image of Winnie Mandela was painted over with the portrait of Maathai.

Jane Norling told me a few years ago that the muralists wanted to honor Maathai who had then just won the Nobel Prize for her work as an environmentalist, human rights advocate and feminist.

To be sure, Maathai’s story is compelling.

Greenbelt is known as a posh mall to Filipinos. In Africa, Maathai’s Green Belt Movement has helped plant more than 30 million trees in the continent, giving aid to nearly a million women.

Achim Steiner, executive director of the United Nation’s environmental program, called her a “force of nature,” according to a New York Times story.

But Maathai faced tough hurdles.

Apparently, African machismo can be just as vicious as the Filipino version. Maathai’s husband divorced her because she was too strong-willed for a woman, according to the New York Times profile. When Maathai criticized the divorce court ruling against her, the judge retaliated by throwing her in jail.

But these setbacks did not stop Maathai. As a Kenyan activist said in the Times report, “Wangari Maathai was known to speak truth to power. She blazed a trail in whatever she did.”

Norling also honored Maathai in an e-mail this week: “Cut short, her life, but such accomplishment.”

There was another reason for the change on the San Francisco mural.

Winnie Mandela, while known for her role in the fight against apartheid in South Africa, also was accused of abusing her power. As Norling told me years ago, Mandela as an activist icon had become “outdated and complicated.”

In fact, as many Filipinos have discovered, activism is, and always has been, complicated.

Some groups calling themselves “revolutionary,” and claiming to represent “the people,” have shown themselves to also be capable of cruelty and abuse. The progressive movement that Lean once led has gone through bitter upheavals, including painful splits that even turned violent.

My friend Lidy Nacpil, Lean’s widow, later broke with the dogmatic, hardline factions of the left, rejecting the movement’s undemocratic, even totalitarian, tendencies.

Four years ago, when I attended the 20th anniversary commemoration of Lean’s murder in Quezon City, Lidy even offered a more humane portrait of Lean.

Yes, he had totally committed his life to the fight for social change, she said – but Lean was also prone to the same narrow machismo of the typical Filipino male. For instance, she recalled, he once became upset after Lidy challenged his views in public. “Tao lang siya – he was human,” she said.

Still, it is inspiring to know that Lean did not suffer the fate of Winnie Mandela on the San Francisco mural.

He’s still there. He was not a saint. He was not some mythical figure. He was human.

But certainly, he still deserves to be on that wall with Maathai, with others who risked everything, including their lives, in fighting for social justice.

On Twitter @KuwentoPimentel. On Facebook at www.facebook.com/benjamin.pimentel