The martyrs of Kidapawan

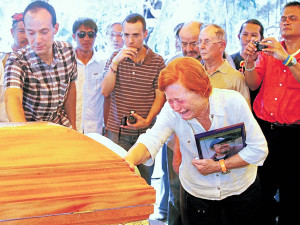

A sister-in-law of martyred priest Fausto Tentorio wails her grief at his funeral attended by more than 10,000 people in Kidapawan City in 2011. INQUIRER FILE

One name stood out for me in the media coverage of the Kidapawan massacre: Father Peter Geremia.

Father Peter is an Italian priest who has lived in Kidapawan since the 1980s. He was there when the massacre happened, helping facilitate negotiations between the farmer protesters and the government and the police. I spoke to him by phone last week to learn more about what happened.

His story is just one account of the incident. But Father Peter’s perspective is significant for a key reason: He’s been part of this community for more than 30 years and knows its painful history. He was instrumental in honoring Kidapawan’s martyrs, which includes two of his friends and fellow priests. He’s lived through Cotabato’s life-and-death struggles with violence and hunger, including the time when he said people were so hungry “they were trying to eat anything.”

I first met Father Peter in the late 1980s, when I covered a Lumad conference in Kidapawan. I didn’t speak Cebuano. Father Peter served as my interpreter in my interviews.

The April 1 massacre happened just as the Diocese of Kidapawan was getting ready for a special day, its annual Day of Martyrs commemoration held on April 11.

The diocese picked that day because that was when Father Peter’s friend and fellow priest, Tulio Favali, was brutally murdered by a local vigilante group in 1985.

“Day of Martyrs is a way to remember all of them,” he told me, referring to all the victims of violence, especially during the Marcos years. Kidapawan initially identified 34 martyrs. The list has continued to grow.

Many thought the killings would stop after the dictatorship’s fall. But in 2011, Father Peter lost another friend, another fellow priest. In October of that year, Father Fausto Tentorio was gunned down by a paramilitary group. It was Father Peter who convened the group that led the campaign for justice for Father Fausto.

“Now 2016, we’re supposed to be in a period of democratic space, but some areas appear to be still under martial law,” he said.

The violence that erupted on April 1 caught him and many others by surprise. That’s because it had seemed that the conflict was on the way to being resolved.

But then a second round of negotiations got delayed when a farmers’ representative asked for more time. He said he was meeting with the protest leaders about returning to the negotiations when the dispersal operation began.

“While we were talking, I heard the commotion at the barricade,” he said. “The authorities used the delay as a reason to force the clearing of the barricade.”

Before the confrontation, Father Peter said he had offered what he described as a form of “criticism” to the farmers, stressing to the protest leaders “that they should consult with the participants on what they will do,” that “they should not place participants in danger without consultation.” He said the leaders assured him everyone was consulted about the protest action.

After the confrontation, he said police told him they suspected the presence of NPA infiltrators.

Did you think that was possible? I asked.

Not really. Probably not, Father Peter said. But then again, it’s really impossible to know, he added. During a protest action of farmers, it’s to be expected that the NPA “will try to increase their influence.” But they certainly wouldn’t have shown up at a rally with their guns.

His response highlighted the complexity of the situation in Northern Cotabato and many parts of Mindanao. It’s no secret that the NPA is strong in that area, especially in remote barrios where many of the farmers are from.

In fact, the April 1 massacre quickly sparked accusations that the underground militant Left forced the confrontation, using the farmers as a pawns.

Even progressive activists critical of the militant Left raised this point.

It’s understandable. The thought also crossed my mind. And it’s mainly because of what happened in the 1987 Mendiola Massacre. Security forces dispersed that peasant demonstration near Malacanang, killing 13 people. Only years later did it become clear to me and others that the underground Left also had pushed the confrontation in order to use it to break off ongoing peace talks.

Still, as I noted in a previous column, it’s a tactic that would work only if the militants were dealing with an undisciplined, even brutal, security force that wouldn’t think twice about opening fire on a group of poor farmers, and a government routinely insensitive to the needs of marginalized communities.

Clearly, the police should be condemned for the 1987 massacre. Clearly, they should be condemned for launching an assault on the Kidapawan farmers.

The farmers were there because they wanted food, Father Peter said. It’s not the first time poor farmers have had to resort to street protests because they were hungry.

Father Peter knows this.

He witnessed and even helped coordinate food related protests in the wake of severe droughts in the 1990s. In fact, in 1992, he was arrested and charged with robbery because he gave aid to protesting farmers who stormed National Food Authority warehouses.

The drought that hit six years later in 1998 was even worse, Father Peter said. He knew at least 60 people who died because of starvation — and because of poisoning. “They were trying to eat anything.”

Food and survival were what the Kidapawan protests were about, he said: “The basic reason for the rally was rice.”

But the April 1 dispersal was not exactly the same as previous protests by hungry farmers.

“The most glaring difference was the shooting of the protesters — which never happened in previous rallies,” he said.

The confrontation could have been avoided. And the Church, he stressed, was seeking to “promote the ways of dialogue, the ways of reconciliation.”

He is not blaming one side or the other at this point. But a small, simple gesture, he lamented, could have defused the situation.

“They should have distributed some rice to the people at the barricades,” he told me, “just to show that they also felt compassion or understanding for the plight of the farmers.”

A small, simple gesture that could have prevented a tragedy and the addition of three more names to Kidapawan’s roster of martyrs.

Visit and like the Kuwento page on Facebook at www.facebook.com/boyingpimentel

On Twitter @boyingpimentel

Like us on Facebook