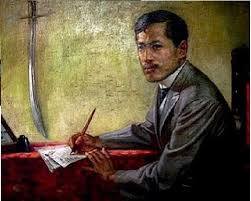

Comparing Dr. Jose Rizal and Ninoy Aquino

Dr. Jose Rizal and Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino

In all of Philippine history, no two national heroes were as similar in how they lived and in how they died than Dr. Jose Rizal and Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., whose 32nd death anniversary we mark this week.

Both came from similar class backgrounds. Their families were just below hacendero level landed gentry; both studied at the elite Ateneo school; both traveled extensively, wrote prolifically, and returned to the Philippines from safety abroad despite warnings that they faced certain death upon setting foot on native soil.

Both were tried on sham charges by kangaroo courts, which sentenced them to death. Both were executed by Filipino soldiers following the orders of the powerful forces who feared their return. Each of their deaths sparked revolutions that overthrew the tyrannies that caused their martyrdoms.

Rizal and Aquino both fit the textbook model of a “tragic hero” — born of privilege, imbued with heroic qualities and fated to endure great suffering. In the classic mold, Prof. Ronald Santora relates, “the hero struggles mightily against this fate and this cosmic conflict wins our admiration.”

Why did Dr. Jose Rizal in 1892 and Ninoy Aquino in 1983 return to the Philippines knowing of the certain death that awaited them upon their arrival? Was it fate or free will?

Dr. Jose Rizal lived and studied in Europe for almost a decade, obtaining advanced degrees in fine arts, medicine (ophthalmology), and even a doctorate in languages. Rizal also wrote two novels, Noli Mi Tangere and El Filibusterismo, which exposed Spanish abuses in the Philippines.

Aside from his academic achievements, Rizal also immersed himself in the Filipino expatriate movement for reforms, organizing forums and contributing regular editorial essays to the movement’s main journal, La Solidaridad.

On November 20, 1891, Rizal moved to Hong Kong and established a private practice in ophthalmology, which drew patients from throughout the crown colony. Before the end of the year, Rizal was able to get his parents and siblings to live with him in a comfortable home in Hong Kong.

While Rizal was overjoyed to be finally reunited with his family, he was deeply dismayed by the factionalism and lack of unity that plagued the Filipino expatriate movement in Europe. As Jose Baron Fernandez noted in his book, (Jose Rizal: Filipino Doctor and Patriot, 1980):

“During the first two months in 1892, the propaganda campaign was in disarray; (Marcelo) Del Pilar in Madrid, abandoned by all except his brother-in-law, (Graciano) Lopez-Jaena in Barcelona, very skeptical of La Propaganda, with its utter neglect of its obligations and, finally, the new committee of La Propaganda, which proposed to Rizal the launching of a new fortnightly paper, as well as the organization of a new party, “the Rizalist party.”.Meanwhile, from Paris came news of the formation of a revolutionary organization called Katipunan (headed by Andres Bonifacio)”.

Ninoy Aquino had been incarcerated in solitary confinement by the dictator Ferdinand Marcos for almost eight years by May of 1980, when he suffered two severe heart attacks within a week of each other. Because of fear of negative publicity if Aquino died while under military custody, first lady Imelda Marcos ordered him released and quickly flown to the U.S. on May 9, 1980. The conjugal dictators expected him to die on an operating table at a hospital in Dallas, Texas, but Aquino somehow defied the odds and survived.

After recuperating from heart surgery, Aquino spent three years in the U.S., setting up a home in the Boston suburb of Newton, Massachusetts, together with two future Philippine presidents, his wife, Cory, and son, Noynoy, and their other children. Ninoy received fellowship grants from Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, worked on the manuscripts of two books and delivered speeches throughout the U.S. denouncing Marcos and martial law.

Aquino also found himself caught in the factional intrigues of the anti-Marcos opposition in the U.S. On the right flank was the Movement for a Free Philippines (MFP) under Sen. Raul Manglapus, which advocated for the return of parliamentary democracy. On the left was the Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino (KDP or Union of Democratic Filipinos), which supported the revolutionary overthrow of the Marcos dictatorship.

In the first quarter of 1983, Aquino received disturbing news of the deteriorating political situation in the Philippines with the consensus belief that the Philippines was just five years away from a full-scale bloody Communist revolution. Because of the declining health of Marcos, Aquino felt it imperative to return to the Philippines to convince Marcos to restore democracy “before extremists take over and make such a change impossible.”

Like Aquino, Rizal too feared the very revolution his own writings had inspired. “Rizal was opposed to Bonifacio’s revolution,” writer-historian F. Sionil Jose explained. “To seek his support, Pio Valenzuela visited him in Dapitan where the Spaniards had exiled him. Rizal argued that Filipinos were not ready for a revolution, that the cost and the bloodshed would be tremendous.”

Seeking to avert bloody revolutions, both freely chose to return back to the Philippines to personally make the case for a non-violent reform alternative. But their pleas fell on deaf ears. Rizal was executed in Luneta (now Rizal Park) on December 30, 1896 by a firing squad of Filipino soldiers acting on the orders of Malacanang Palace. Ninoy was killed at the tarmac of the Manila International Airport (now the Ninoy Aquino International Airport) on August 21, 1983 by an execution squad of Filipino soldiers acting also on the orders of Malacanang Palace.

Just before returning to the Philippines, Rizal wrote a letter to the Filipino people dated 20 June 1892 where he explained:

“The step I have taken or am about to take is very risky no doubt and I do not have to say that I have given it much thought. I know that almost everyone is against it but I know too that almost no one knows what goes in my heart. I cannot go on living knowing that so many suffer unjust persecution because of me … I also want to show those who deny our patriotism that we know how to die doing our duty and for our convictions. What does death matter if one dies for what one loves, for one’s country and loved ones?”

In the statement he planned to read upon his arrival at the Manila airport, Aquino wrote:

“I have returned on my free will to join the ranks of those struggling to restore our rights and freedoms through nonviolence. I seek no confrontation. I only pray and will strive for a genuine national reconciliation founded on justice. I am prepared for the worst, and have decided against the advice of my mother, my spiritual adviser, many of my tested friends and a few of my most valued political mentors. A death sentence awaits me. Two more subversion charges, both calling for death penalties, have been filed since I left three years ago and are now pending with the courts. I could have opted to seek political asylum in America, but I feel it is my duty, as it is the duty of every Filipino, to suffer with his people especially in time of crisis. I never sought nor have I been given assurances or promise of leniency by the regime. I return voluntarily armed only with a clear conscience and fortified in the faith that in the end justice will emerge triumphant. According to Gandhi, the willing sacrifice of the innocent is the most powerful answer to insolent tyranny that has yet been conceived by God and man.”

Rizal’s execution triggered the Katipunan revolution that led to the Filipino people’s overthrow of Spanish rule. Ninoy’s execution sparked the People Power revolution that led to the ouster of the Marcoses from the Philippines.

In their cosmic conflicts against their fates, by their words and by their deeds, Dr. Jose Rizal and Ninoy Aquino transformed the Philippines and the Filipino people.

(Rodel Rodis taught Philippine History at San Francisco State University. He can be reached at Rodel50@gmail.com or by mail at the Law Offices of Rodel Rodis at 2429 Ocean Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94127).

Like us on Facebook