It’s official: “presidentiable,” “barkada” and “balikbayan” have been included in the English dictionary.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) announced Thursday that several Filipino terms and uniquely Filipino usages of common English words are among those included in the latest update of the lexicon, recognized as the “definitive record of the English language.”

In a news release sent to the Inquirer, the OED said the dictionary’s latest update “sees the inclusion of a number of words from Philippine English as part of our ongoing commitment to recording words from all varieties of English, throughout the world.”

READ: Selfie tops twerk as Oxford’s word of the year | English dictionary to add Pinoy pork barrel-inspired words

“There are new senses of common English words like gimmick to mean ‘a night out with friends’; loanwords from Spanish (like estafa ‘fraud’) and Tagalog like barkada (‘group of friends’); and formations in English that are only used in Philippine English, like carnap (‘to steal a car’) and presidentiable (‘a person who is a likely or confirmed candidate for president’),” the OED said.

“Evidence for these usages is not just found in the Philippines but also in parts of the United States that have large Filipino populations,” it said.

The latest OED update includes 500 new words, more than 900 newly revised and updated words, and more than 2,400 new senses or definitions of existing words.

“This makes the OED one of the largest and longest-running language research projects in the world,” the OED said.

Other new words, new descriptions and definitions from Philippine English include the following (quoted verbatim from OED):

barangay (noun): In the Philippines: a village, suburb, or other demarcated neighbourhood; a small territorial and administrative district forming the most local level of government. [First recorded 1840]

balikbayan (noun): A Filipino visiting or returning to the Philippines after a period of living in another country. [1976]

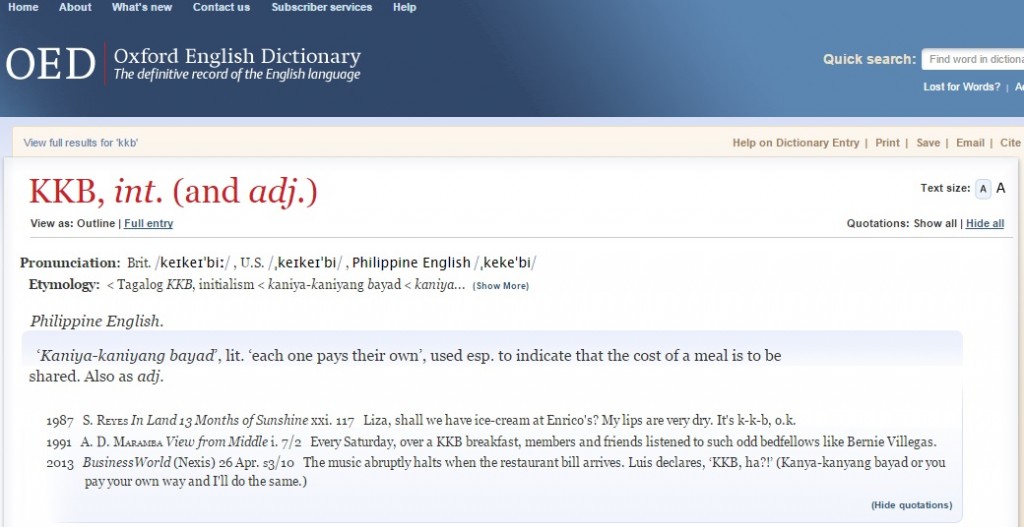

KKB (interjection): ‘Kaniya-kaniyang bayad’, literally ‘each one pays their own’, used especially to indicate that the cost of a meal is to be shared. It can also be used as an adjective. [1987]

high blood: (a) n.colloq. hypertension; (b) adj.Philippine English angry, agitated.

despedida (noun): More fully despedida party. A social event honouring someone who is about to depart on a journey or leave an organization; a going-away party. [1929]

halo-halo (noun): A dessert made of mixed fruits, sweet beans, milk, and shaved ice, typically topped with purple yam, crème caramel, and ice cream. [1922]

sari-sari store (noun): A small neighbourhood store selling a variety of goods. [1925]

utang na loob (noun): A sense of obligation to return a favour owed to someone. [1906]

The June 2015 update of the OED includes a total of 40 words culled from Philippine usage of English, said Danica Salazar, a Filipino lexicographer who works as Consultant Editor on the OED.

This is the “largest single batch” of items from the Philippines “all published at the same time” on the dictionary, Salazar told the Inquirer from London via email interview. It was also the first time for OED to use Philippine English as a label for the Filipino variety of language use,” Salazar said.

“In this particular batch of Philippine English words, we made sure to have a balanced selection of items that show all the ways in which Filipinos have adapted English vocabulary to suit their communicative needs. Not just borrowings from Tagalog such as halo-halo, barangay and suki, but also hybrid expressions (balikbayan box, sari-sari store, kikay kit), derivations (presidentiable), compounds (batchmate), blends and clippings (mani-pedi), initialisms (KKB), loan translations (go down as in to get off a vehicle, a translation of Tagalog bumaba); conversions from one part of speech to another (adjectival use of noun phrase high blood), and even complete changes in meaning (gimmick, salvage),” she said.

Such addition is important as this shows how the OED strives “to remain current and relevant,” being “a dictionary that considers itself to be the ultimate historical record of the English language,” she said.

The first Filipino word to be added on the dictionary was “abaca,” which came out on OED’s complete first edition in 1928.

She said the Philippine Daily Inquirer, the country’s newspaper of record, was also “a good source of illustrative quotations” that showed the usage of Philippine English terms.

“…[M]eaning that your newspaper is actually in the dictionary,” Salazar said.

OED examples quoting the Inquirer include the use of terms such as baro’t saya, batchmate, estafa, and gimmick.

Expect further updates in Friday’s edition of the Philippine Daily Inquirer in print or tablet form at Inquirer Plus (https://inq.ph/inqplus) and on Radyo Inquirer 990AM. TVJ/IDL