It’s a family affair

NEW YORK CITY — The written history of Filipinos in the United States has usually been centered on Hawai’i and the West Coast. This is not surprising, given that when the Philippines was taken over by the U.S. as a colony (their only official one) in 1898, the migration of Pinoys began in 1906, as waves of cheap labor proceeded to the plantations, farms, fruit orchards and canneries initially in Hawai’i then to California, Washington, and to a lesser extent, Alaska.

The West Coast was the main destination as well for such Asian groups as the Chinese and the Japanese. Hence, Asian American history, including that of Filipino Americans, has tended to be West Coast-centric. The major narratives familiar to anyone with an interest in the stories of Asian America all took place on the Pacific Coast, whether we talk about the 1848 Gold Rush, with the Chinese seeking their fortune in Gold Mountain (as they referred to the U.S. then), or the unjust and racist internment of Japanese and Japanese-Americans during World War II, or the labor organizing done by Filipino agricultural workers in the period right after the stock market crash of 1929 all the way to the bombing of Pearl Harbor—a period powerfully chronicled in the immigrant and American classic, America Is in the Heart, by Carlos Bulosan. Rather than Ellis Island, immigrant gateway to the East Coast, Angel Island was the entry point for most Asians then.

Consequently, conventional history tends to overlook the presence of Pinoys outside the well-known centers. Pinoy history on the East Coast is assumed to have weight only after 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act was passed by Congress, abolishing the national-origins basis that favored immigrants from Europe (mainly from the north and the west) and discriminated against Asians and Africans. The liberalization saw a marked increase in the population of people of color, in addition to African Americans. By the 1990s, 31 percent of immigrants were Asian or of Asian descent, and only 16 percent were European. Between 1965 and 2000, after Mexicans, Filipinos constituted the largest immigrant group.

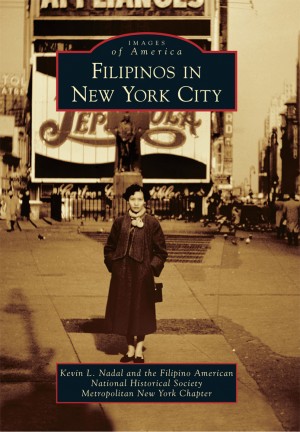

It is certainly true that the number of Filipinos in New York City increased significantly post-1965, but they—we—have been a presence in Gotham for at least a century, even earlier if one takes into account Rizal’s brief stay in the city from May 13 to May 16, 1888, the culmination of his North American sojourn before his departure for London. This is a fact mentioned in Kevin Nadal’s just-released Filipinos in New York City—part of “Images of America,” a series published by Arcadia Publishing where each title in the series “celebrates the history of neighborhoods, towns, and cities across the country”—a collection of archival and family-owned photographs, with texts by Nadal laying out their history. (Full disclosure: I am one of the Filipinos mentioned in the book.)

Nadal is a native Californian who moved to this city in 2002 to earn his doctorate in counseling psychology at Columbia University. He now heads the New York chapter of the Filipino American National Historical Society and teaches at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. He states in his Introduction that since most studies on Filipinos in the U.S. focused predictably on Hawai’i and the West Coast, “it was important for me to learn and educate others about the experiences of Filipinos on the East Coast. … I had no idea how much I would uncover.”

Indeed, I believe the book is the first to zero in exclusively on Filipino lives in the city that never sleeps. There have been stand-alone essays and sections in various books, but never one such as this. Consisting of seven chapters, Filipinos in New York City covers the early years, from 1908, with student scholars, sponsored by the U.S. government and known as pensionados, arriving via Ellis Island to attend New York University or Columbia University. There are photographs of a young Carlos P. Romulo, also a pensionado, and of Fernando Amorsolo, who lived in the city for several years.

Article continues after this advertisementAmong topics the other chapters examine are how World War II and the 1965 immigration act shaped Filipino presence; the growth of Pinoy enclaves in the city’s five boroughs; and the establishment of Filipino American organizations that range from cultural nonprofits such the Queens-based Topaz Arts and Filipino American Museum (FAM), to health-and-community-oriented centers such as APICHA, FAHSI, Damayan, and Philippine Forum. Nadal’s book includes various shots of individual Pinoy New Yorkers known and unknown and of groups of Filipinos posing (in that well-known ritual known colloquially as kodakan) in front of such New York landmarks as the Brooklyn Bridge, Rockefeller Center, St. Patrick’s Cathedral and Times Square. The book concludes with a 2000 photo of Engineer Hector Rogan Tamayo and his wife, with the ill-fated Twin Towers in the background. Tamayo was working on the 86th floor of the second tower on September 11, 2001 and never made it out of the building.

Article continues after this advertisementThere are gaps in the coverage. There is for instance nary a mention of the political scene in the city’s Filipino community when the Marcoses were in power, or of the different Pinoy newspapers and journals in circulation, such as The Filipino Reporter, The Filipino Express, and Ningas Cogon, but Filipinos in New York City doesn’t pretend to be exhaustive or definitive, which would require a substantially larger work. Free of mind-numbing jargon—Nadal thankfully doesn’t feel the need to parade his academic credentials—the book more significantly is at heart a family album, albeit a comprehensive one that invites you to thumb through its pages leisurely and get an intimate look at Filipinos who play an essential part in the mosaic and theater that is New York City.

Copyright L.H. Francia 2015

Like us on Facebook