North Borneo (Sabah): An annotated timeline 1640s-present

By Manuel L. Quezon III

Note from the author: I am sharing a timeline I have compiled of key events and accompanying literature on the North Borneo (Sabah) issue. This timeline is being shared for academic and media research purposes. It is not being published as an official statement of policy in any shape or form, nor does this timeline purport to be representative of the views of the Philippine government.

1640s

Spain signed peace treaties with the strongest sultanates, Sulu and Maguindanao, recognizing their de facto independence.[1]

1704

Sultan of Sulu became sovereign ruler of most of North Borneo by virtue of a cession from the Sultan of Brunei whom he had helped in suppressing a rebellion.

There is no document stating the grant of North Borneo from Sultan of Brunei to Sultan of Sulu, but it is accepted by all sides.[2]

March 17, 1824

Treaty of London signed by the Netherlands and Great Britain

Allocates certain territories in the Malay archipelago to the United Kingdom and the Netherlands (Dutch East Indies).[3]

September 23, 1836

Treaty of Peace and Commerce between Spain and Sulu, signed in Sulu

Granting Spanish protection of sultanate, mutual defense, and safe passage for Spanish and Joloan ships between ports of Manila, Zamboanga, and Jolo.[4]

Ortiz: Spain did not claim sovereignty over Sulu, but merely offered “the protection of Her Government and the aid of fleets and soldiers for wars…”[5]

1845

Muda Hassim, uncle of the Sultan of Sulu, publicly announced as successor to the Sultanate of Sulu with the title of Sultan Muda: he was also the leader of the “English party,”(today the term for Crown Prince is Raja Muda)[6]

The British Government appoints James Brooke as a confidential agent in Borneo[7]

The British Government extends help to Sultan Muda to deal with piracy and settle the Government of Borneo[8]

April 1846

Sir James Brooke receives intelligence that the Sultan of Sulu ordered the murder of Muda Hassim, and some thirteen Rajas and many of their followers; Muda Hassim kills himself because he found that resistance is useless. [9]

July 19, 1846

Admiral Thomas Cochrane, Commander-in-chief of East Indies and China Station of the Royal Navy, issued a Proclamation to cease hostilities (“piracy,” crackdown versus pro-British faction) if the Sultan of Sulu would govern “lawfully” and respect his engagements with the British Government

If the Sultan persisted, the Admiral proclaimed that the squadron would burn down the capital of the sultanate.[10]

May 7, 1847

James Brooke is instructed by the British Government to conclude a treaty with the Sultan of Brunei

British occupation of Labuan is confirmed and Sultan concedes that no territorial cession of any portion of his country should ever be made to any foreign power without the sanction of Great Britain[11]

May 29, 1849

Convention of Commerce between Britain and the Sultanate of Sulu

Sultan of Sulu will not cede any territory without the consent of the British. [12]

April 30, 1851

Treaty signed with Spain by the Sultan of Sulu, Mohammed Pulalun

The Sultanate of Sulu was incorporated into the Spanish Monarchy.[13]

January 17, 1867

Earl of Derby to Lord Odo Russel:

that, whatever Treaty rights Spain may have had to the sovereignty of Sulu and its dependencies, those rights must be considered as having lapsed owing to the complete failure of Spain to attain a de facto control over the territory claimed.

May 30, 1877

Protocol of Sulu signed between Spain, Germany, and Great Britain, providing free movement of ships engaged in commerce and direct trading in the Sulu Archipelago

British Ambassadors in Madrid and Berlin were instructed that the protocol implies recognition of Spanish claims over Sulu or its dependencies.

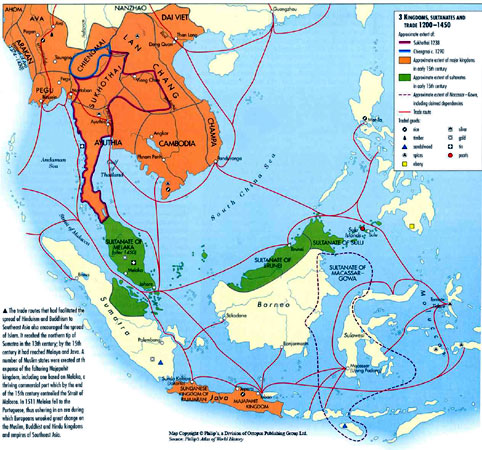

At this point the following western countries have possessions in Southeast Asia:

1. British = Singapore, Malaya, Brunei, Sarawak, and North Borneo

2. Germany = Papua New Guinea

3. Netherlands = Indonesia

4. Spain = Philippines, Guam, Marshall Islands, Caroline Islands

5. France = Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia (French IndoChina)[14]

December 1877

Expeditions of Alfred Dent to control north part of Borneo began

Alfred Dent, member of the commercial house of Dent Brothers and Co. of London [15]

January 22, 1878

Sir Alfred Dent obtains sovereign control over the northern part of Borneo for 5,300 ringgit ($5,000) from the Sultans of Brunei and Sulu. See contending translations of relevant portions of this document. See also the Spanish translation. See another English translation.

Concessions would later be confirmed by Her Majesty’s Royal Charter in November, 1881 granted to the British North Borneo Co.

The territory of the Sultan of Sulu over the island of Borneo,

commencing from the Pandassan River on the north-west coast and extending along the whole east coast as far as the Sibuco River in the south and comprising amongst other the States of Paitan, Sugut, Bangaya, Labuk, Sandakan, Kina Batangan, Mumiang, and all the other territories and states to the southward thereof bordering on Darvel Bay and as far as the Sibuco river with all the islands within three marine leagues of the coast. [16]

Sultan of Sulu Mohammed Jamalul Alam appoints Baron de Overbeck as Datu Bendajara and Raja of North Borneo

(Baron de Overbeck, Austrian national heavily connected with the house of Dent and Co. at Hong Kong. Overbeck was sent to Borneo as a representative of Dent and Co. to enter negotiations with Sultans and Chiefs of Brunei and Sulu – Dec 1878 Statement and Application of Debt of Dent and Overbeck to the Marquis of Salisbury)[17]

Sultan of Sulu Mohammed Jamalul Alam (Translation of Deed of 1878 by Prof. Harold Conklin) wrote letters to the Governor of Jolo, Carlos Martinez and the Captain-General Malcampo to revoke what he termed the lease he granted over North Borneo. [18]

July 4, 1878

The Sultan of Sulu Mohammed Jamalul Alam sends a letter to the Captain-General of the Philippines.

According to the letter of the Sultan, Sandakan was not ceded to the United Kingdom but was only leased. The Sultan added that he only did this under the threat of attack from the British[19]

July 22, 1878

Bases of Peace and Capitulation signed in Jolo.

Sultan of Sulu, Mohammed Jamalul Alam declared the sovereignty of Spain over the Archipelago of Suluand its dependencies while granting free exercise of religion and customs for his people. [20]

See also letter of July 24, 1878 from the Governor of Sulu to Baron de Overbeck.

British, German, French, Dutch, and the Spaniards agree on their spheres of influence in Southeast Asia.[21]

December 2, 1878

Dent and Overbeck apply for a Charter of Incorporation from Queen Victoria[22]

April 16, 1879

Acting Governor Treacher writes to the Colonial Office, objecting to hoisting of Spanish flag over North Borneo.

November 5, 1879

Memorandum by the Duke of Tetuan to the Marquis of Salisbury.

November 1, 1881

Queen Victoria grants Charter of Incorporation to the British North Borneo Company

British North Borneo Company now does actually exist “as a Territorial Power” and not “as a Trading Company”[23]

November 16, 1881

Spaniards protest granting of Royal Charter

By virtue of treaties of capitulation of 1836, 1851, and 1878, Spain exercised sovereignty over Sulu and its dependencies including North Borneo; Sultan of Sulu had no right to enter into any treaties or make any cessions whatsoever [24]

January 7, 1882

British Foreign Minister Earl Granville’s letter says Crown assumes no dominion or sovereignty over the territories occupied by the Company, nor does it purport to grant to the Company any powers of Government thereover.

Crown merely recognizes the grants of territory and the powers of government made and delegated by the Sultans in whom the sovereignty remains vested. [25]

March 7, 1885

Spanish claims to Borneo abandoned by Protocol of Sulu entered into by England, Germany and Spain

Spanish supremacy over the Sulu Archipelago was recognised on condition of their abandoning all claim to the portions of Northern Borneo which are now included in the British North Borneo Company’s concessions[26]

May 12, 1888

While civil war was ongoing in Sulu, “State of North Borneo” is made a British protectorate

An agreement between the British North Borneo Company and Great Britain; British Government admits the North Borneo Company derived its rights and powers to govern the territory.[27]

June 14, 1888

British Protectorate established over Sarawak[28]

September 17, 1888

British Protectorate established over Brunei[29]

1892

Jose Rizal proposes to the Spanish government to establish a Filipino colony in Sabah. This plan, however, does not push through.

1896

Federated Malay States

Provinces included: Negeri Sembilan, Pehang, Perak and Selangor[30]

1894-1936

Sultan Jamalul Kiram II rules the Sultanate of Sulu

December 10, 1898

Spain cedes the Philippine Islands to the United States of America. The treaty lines did not include North Borneo (Sabah).[31]

1899

President Aguinaldo invites the Sultan of Sulu to join the newly-established First Republic of the Philippines.

Malolos Congress appointed representatives for Jolo: Benito Legarda and Victor Papa[32]

August 20, 1899

Kiram-Bates Treaty

Treaty acknowledged the “sovereignty of the United States over Jolo and its dependencies”

December 5, 1899

In his State of the Union Message, William McKinley discusses American policy towards the Sultanate of Sulu:

The authorities of the Sulu Islands have accepted the succession of the United States to the rights of Spain, and our flag floats over that territory. On the 10th of August, 1899, Brig. Gen. J. C. Bates, United States Volunteers, negotiated an agreement with the Sultan and his principal chiefs, which I transmit herewith. By Article I the sovereignty of the United States over the whole archipelago of Jolo and its dependencies is declared and acknowledged.

The United States flag will be used in the archipelago and its dependencies, on land and sea. Piracy is to be suppressed, and the Sultan agrees to co-operate heartily with the United States authorities to that end and to make every possible effort to arrest and bring to justice all persons engaged in piracy. All trade in domestic products of the archipelago of Jolo when carried on with any part of the Philippine Islands and under the American flag shall be free, unlimited, and undutiable. The United States will give full protection to the Sultan in case any foreign nation should attempt to impose upon him. The United States will not sell the island of Jolo or any other island of the Jolo archipelago to any foreign nation without the consent of the Sultan. Salaries for the Sultan and his associates in the administration of the islands have been agreed upon to the amount of $760 monthly.

Article X provides that any slave in the archipelago of Jolo shall have the right to purchase freedom by paying to the master the usual market value. The agreement by General Bates was made subject to confirmation by the President and to future modifications by the consent of the parties in interest. I have confirmed said agreement, subject to the action of the Congress, and with the reservation, which I have directed shall be communicated to the Sultan of Jolo, that this agreement is not to be deemed in any way to authorize or give the consent of the United States to the existence of slavery in the Sulu archipelago. I communicate these facts to the Congress for its information and action.

February 1, 1900

Kiram-Bates Treaty submitted to the U.S. Senate by William McKinley:

In compliance with the resolution of the Senate of January 24, 1900, I transmit herewith a copy of the report and all accompanying papers of Brig-Gen. John C. Bates, in relation to the negotiations of a treaty or agreement made by him with the Sultan of Sulu on the 20th day of August, 1899.

I reply to the request and said resolution for further information that the payments of money provided for by the agreement will be made from the revenues of the Philippine Islands, unless Congress shall otherwise direct.

Such payments are not for specific services but are a part consideration due to the Sulu tribe or nation under the agreement, and they have been stipulated for subject to the action of Congress in conformity with the practice of this Government from the earliest times in its agreements with the various Indian nations occupying and governing portions of the territory subject to the sovereignty of the United States.

Not ratified by the U.S. Senate, President Theodore Roosevelt abrogates treaty[33]

November 7, 1900

Consolidate the American possessions in the Sulu archipelago by including the islands of Sibutu and Cagayan, both of which had always formed part of the possessions of the Sulu sultanate.[34]

November 7, 1900

British North Borneo Company obtains from Sultan of Sulu even more territory

December 3, 1900

In his State of the Union Message, William McKinley provides details on the Convention of 1900:

I feel that we should not suffer to pass any opportunity to reaffirm the cordial ties that existed between us and Spain from the time of our earliest independence, and to enhance the mutual benefits of that commercial intercourse which is natural between the two countries.

By the terms of the Treaty of Peace the line bounding the ceded Philippine group in the southwest failed to include several small islands lying westward of the Sulus, which have always been recognized as under Spanish control. The occupation of Sibutd and Cagayan Sulu by our naval forces elicited a claim on the part of Spain, the essential equity of which could not be gainsaid. In order to cure the defect of the treaty by removing all possible ground of future misunderstanding respecting the interpretation of its third article, I directed the negotiation of a supplementary treaty, which will be forthwith laid before the Senate, whereby Spain quits all title and claim of title to the islands named as well as to any and all islands belonging to the Philippine Archipelago lying outside the lines described in said third article, and agrees that all such islands shall be comprehended in the cession of the archipelago as fully as if they had been expressly included within those lines. In consideration of this cession the United States is to pay to Spain the sum of $100,000.

A bill is now pending to effect the recommendation made in my last annual message that appropriate legislation be had to carry into execution Article VII of the Treaty of Peace with Spain, by which the United States assumed the payment of certain claims for indemnity of its citizens against Spain. I ask that action be taken to fulfill this obligation.

April 22, 1903

Additional $300 a year paid for a Confirmatory Deed stipulating that certain islands not specifically mentioned in the Deed of 1878 had in fact been always understood to be included therein.[35]

November 19, 1906

Note of the U.S. Department of State to the British Embassy in Washington, D.C.

…the US Department of State stated that Sabah was not an Imperial possession of the British Crown, that the British North Borneo Company which had leased Sabah from the Sultan of Sulu, did not have a national status, and that the company did not have an administration with the standing of a government…[36]

March 22, 1915

Governor of Mindanao and Sulu Frank W. Carpenter signs an agreement with the Sultan of Sulu which relinquishes the Sultan’s, and his heirs’, right to temporal sovereignty, tax collection, and arbitration laws. In exchange, the Sultan gets an allowance, a piece of land and recognition as religious leader.[37]

May 4, 1920

Temporal Sovereignty and Ecclesiastical Authority of the Sultanate of Sulu

…Gov. Frank W. Carpenter acknowledged the temporal sovereignty and ecclesiastical authority of the Sultanate of Sulu beyond the territorial jurisdiction of the United States government especially with reference to the portion of the Island of Borneo (Sabah) which is a dependency of the Sultan of Sulu.[38]

Governor Frank W. Carpenter in a letter to the Director of Non-Christian Tribes stresses in a letter that the signing of the Agreement meant the “termination of all the rights of temporal sovereignty” which the Sultan had previously exercised in Sulu within American territory without prejudice to North Borneo.

Clarification: without prejudice or effect as to the temporal sovereignty and ecclesiastical authority of the Sultanate beyond the territorial jurisdiction of the U.S. Government, especially with reference to that portion of the island of Borneo which, as a dependency of the Sultanate of Sulu is understood to be held under lease by the Chartered Company which is known as the British North Borneo Company.[39]

British North Borneo Company attempts to have Sultan Jamalul Kiram to take up residence in Sandakan to acquire a good title to the ownership of the territories

A palace was offered in Sandakan to place himself under their protection. On two occasions, Gov. Carpenter had to send the Chief of Police of Jolo to bring the Sultan back from Sandakan [40]

June 11, 1926

Bacon Bill

Rep. Bacon files bill to separate Mindanao from the Philippines. [41]

January 2, 1930

Clarifies which islands in the region belong to U.S. and which belong to the State of North Borneo; delimits the boundary between the Philippine Archipelago (under U.S. sovereignty) and the State of North Borneo (under British protection) [42]

November 15, 1935

Philippine Commonwealth is inaugurated.

1935 Constitution

Article I, National Territory:

The Philippines comprises all the territory ceded to the United States by the Treaty of Paris concluded between the United States and Spain on the tenth day of December, eighteen hundred and ninety-eight, the limits which are set forth in Article III of said treaty, together with all the islands embraced in the treaty concluded at Washington between the United States and Spain on the seventh day of November, nineteen hundred, and the treaty concluded between the United States and Great Britain on the second day of January, nineteen hundred and thirty, and all territory over which the present Government of the Philippine Islands exercises jurisdiction.

June 11, 1936

Sultan of Sulu (Jamalul Kiram) dies and the question of the perpetuation of the Sultanate is raised. Sultan Muwallil Wasit succeeds his brother but dies before he was crowned.[43]

Brother is the claimant though his niece Dayang-Dayang, married to Datu Ombra, wishes to be Sultana. Quezon considers her to be the ablest of the Moros but Mohameddan law does not permit a woman to be Sultan. Harrison points out large portion of political sovereignty already surrendered to Wood in 1903 and Carpenter in 1915. Quezon to recognize Sultan only as the religious head. British North Borneo Company expressed interest because of the stipend paid by the Company to the Sultan. [44]

January 29, 1937

Datu Ombra Amilbangsa is proclaimed Sultan of Sulu

He is the husband of Dayang Dayang Hadji Piandao. His title becomes Sultan Mohammed Amirul Ombra Amilbangsa. His Crown Prince is Esmail Kiram, having given up his own present pretentions to the Sultanate[45]

About the same time, Datu Tambuyong is proclaimed and crowned Sultan.

His title becoming, Sultan Jainal Aberin. He chose Datu Buyungan, his brother and present husband of Tarhata Kiram as Crown Prince.[46]

1937-1950

While Esmail Kiram I did not assume the throne, Dayang Dayang makes her husband, Datu Ombra Amilbangsa, sultan. Datu Tambuyong is also crowned sultan but by opposing Moro leaders.

Datu Ombra is named Sultan Amirul Ombra Amilbangsa; Datu Tambuyong is crowned Sultan Jainal Aberin. The two claimed the sultanate from 1937-1950.[47]

May 9, 1937

Through the efforts of Dayang Dayang, the British resume payment of lease. [48]

September 20, 1937

Memorandum on Administration of Affairs in Mindanao of President Quezon to Secretary Quirino: Titles of Datus and Sultans are recognized but have no Official Rights and Powers[49]

October 2, 1937

Representative of Sulu Datu Amilbangsa writes to President Quezon.

Datu Amilbangsa claims that the policy as released covering this subject was most unnecessary, as the non-recognition has already taken effect since the abrogation of the Bates Treaty and the implantation of the Civil Government in the regions referred to. [50]

October 8, 1937

Three-point policy for Mindanao and Sulu letter from the Executive Secretary Jorge Vargas to the Representative of Sulu Datu Amilbangsa.

Jorge Vargas communicates President Manuel L. Quezon’s policy to recognize the titles of Datus and Sultans but no official rights and powers.[51]

December 18, 1939

High Court of the State of North Borneo hands down decision in Civil Suit No. 169/39 in it, North Borneo Chief Justice C.F.C. Mackaskie stated that the heirs of the sultan were legally entitled the payment for North Borneo, which the decision calls “cession payment” on the basis of an English translation by Maxwell and Gibson.

In the same decision, Mackaskie renders an obiter dictum opinion or side note, that the Philippine Government is the successor-in-sovereignty to the Sultanate of Sulu.

This obiter dictum however, does not establish a legal precedent, and was furthermore based on a report from the British Consul in Manila, claiming that the Commonwealth Government had abolished the Sultanate of Sulu.

Note: The first to challenge the Maxwell & Gibson translation used by the High Court of the State of North Borneo is Francis Burton Harrison, who pointed out in 1946-47 that Chief Justice Mackaskie used the British translation of the North Borneo agree which stated that the land was ceded; he submits a different translation by Prof. Conklin, obtained through H. Otley Beyer [52]

April 4, 1940

Dayang Dayang renounces her claim against the Philippine Government over the Sultanate of Sulu[53]

1942-1945

World War II

1946

Malayan Union Created

Provinces included:

Federated Malayan States

Unfederated Malayan States (Johor, Kedah, Kalantan, Perils, Terengganu)

Malacca

Penang[54]

June 18, 1946

American attorneys representing the heirs of the Sultan of Sulu denounce British action of annexation of North Borneo calling it an unauthorized act of agression.[55]

June 26, 1946

British North Borneo Company cedes colony to the Crown. Thus, annexing North Borneo to the British Empire.[56]

July 4, 1946

Inauguration of the Third Philippine Republic

July 10 (or 16), 1946

British Government annexed the territory of North Borneo as a Crown Colony[57]

September 26, 1946

Presidential Adviser on Foreign Affairs, Francis Burton Harrison, writes a recommendation to the Department of Foreign Affairs that the Philippines should launch a protest against Britain’s annexation.

Francis Burton Harrison was former American Governor-General of the Philippines. He became a Filipino Citizen in 1936 and was an advisor on Foreign Affairs to President Manuel Roxas.[58]

December 8, 1946

Francis Burton Harrison writes a second memorandum on the government of the Sultanate of Sulu.

In the memorandum, Francis Burton Harrison mentions that he asked a Professor Otley Beyer to translate the original lease of North Borneo. Beyer translates it as the land being Leased and not as ceded.[59]

February 27, 1947

Francis Burton Harrison: Recommendation to Secretary of Foreign Affairs and Vice President Elpidio Quirino

The action of the British Government in announcing on the 16th of July (1946), just 12 days after the inauguration of the Republic of the Philippines, a step taken by the British Government unilaterally, and without any special notice to the Sultanate of Sulu, nor consideration of their legal rights, was an act of political aggression, which should be promptly repudiated by the Government of the Republic of the Philippines. The proposal to lay this case before the United Nations should bring the whole matter before the bar of world opinion.[60]

January 31, 1948

The Federation of Malaya was created

Malay States became British Protectorates.

Malacca and Penang remained as British Colonies.[61]

1950-1974

Sultan Esmail Kiram assumes the throne until his death in 1974.

April 28, 1950

House of Representatives approved Concurrent Resolution No. 42 expressing the “sense of the Congress of the Philippines that North Borneo belongs to the heirs of the Sultan of Sulu and the ultimate sovereignty of the Republic of the Philippines and authorizing the President (Elpidio Quirino) to conduct negotiations for the restoration of such ownership and sovereign jurisdiction over said territory.” The Senate did not approve the Resolution.

Reps. Macapagal (Pampanga), Rasul (Mindanao and Sulu), Escarreal (Samar), Cases (La Union), Tizon (Samar), Tolentino (Manila), and Lacson (Manila) author the Resolution. [62]

September 4, 1950

Philippines advised British Government that a dispute regarding ownership and sovereignty over North Borneo existed between the two countries.[63]

August 30, 1955

Vice President Carlos P. Garcia and the British Ambassador to Manila signed an agreement that provided for the employment and settlement of 5,000 skilled and unskilled Filipino agriculturists and miners in North Borneo

Agreement not implemented as North Borneo employers feared multiple suits arising from claims of Filipino laborers: they had found a sizable number of Indonesians willing to work on a temporary basis[64]

January 1957

Governor of North Borneo visits Manila to implement the 1955 labor treaty.

500-man delegation of Filipino Muslims present resolution to President Ramon Magsaysay calling for direct negotiations with the British to return North Borneo to the Philippines. Magsaysay did not act on the resolution.

British response: United Kingdom High Commissioner for Southeast Asia said it would not take seriously the demands of Moros in the Philippines for certain areas of North Borneo.[65]

July 31, 1957

The Federation of Malaya Act was signed.

The Federation of Malaya was established as a sovereign country within the British Commonwealth. [66]

November 25, 1957

Muhammad Esmail Kiram, Sultan of Sulu, issued a proclamation declaring the termination of the Overbeck and Dent lease, effective January 22, 1958.

All lands were to be deemed restituted henceforth to the Sultanate of Sulu[67]

1957

“A syndicate headed by Nicasio Osmeña acting as attorney-in-fact for the heirs, attempted without success to negotiate with the British Foreign Office for a lump sum payment of $15 million in full settlement of the lease agreement.”[68]

August 31, 1957

Peninsular Malaya granted independence by Britain[69]

May 27, 1961

Inclusion of North Borneo (Sabah) in the concept of Malaysia after the UK talks

It was during this time when then President Diosdado Macapagal was forced to initiate the filing of the Philippine claim in North Borneo (Sabah) as it was being considered as a member of the proposed concept of Malaysia broached by Prime Minister Tengku Abduk Rahman in Singapore [70]

February 5, 1962

Attorneys of the heirs of the Sultan of Sulu wrote to the Department of Foreign Affairs with the desire to have the territory included as part of the national territory of the Republic of the Philippines;

Ortiz: J.C. Orendain, acting as counsel for the heirs – regain proprietary rights to North Borneo and that sovereignty be turned over to the Philippine Republic[71]

April 24, 1962

Heirs of the Sultan of Sulu ceded sovereignty rights over Sabah to the Philippine Government[72]

Resolution No. 321 unanimously adopted by House of Representatives, urging President Macapagal to take the necessary steps for the recovery of North Borneo (Sabah).

Filed by Rep. Godofredo Ramos (Aklan) the resolution read: “It is the sense of the House of Representatives that the claim to North Borneo is legal and valid.”

April 25, 1962

President Macapagal called Sultan Mohammad Esmail Kiram to Malacañan Palace to discuss the Philippine Claim on North Borneo.[73]

Acceptance by the Republic of the Philippines, represented by Acting Secretary of Foreign Affairs Salvador P. Lopez of the cession and transfer of territory of North Borneo[74]

April 29, 1962

Ruma Bechara advised Sultan Esmail Kiram to cede to the Republic of the Philippines the territory of North Borneo, and the full sovereignty, title and dominion over the territory, without prejudice to such proprietary rights as the heirs of Sultan Jamalul Kiram may have.[75]

May 25, 1962

British Government sends a note to the Philippines asserting its claim on Sabah; says no dispute on sovereignty and ownership of Sabah.

Note is sent by British Ambassador to the Vice President and Secretary of Foreign Affairs Emmanuel Pelaez.[76]

June 22, 1962

Acting Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Salvador P. Lopez, handed a note to the British Ambassador to Manila asserting the Philippine claim on North Borneo.

In implementation of House Resolution 321.[77]

August 7, 1962

British Government reply to June 22, 1962 note of Philippines again asserting its sovereignty over Sabah

Note is sent by Secretary of State to Philippine Ambassador in London[78]

August 29, 1962

Resolution of the Ruma Bechara of Sulu authorizing the Sultan in council to transfer his title and sovereignty over the inhabitants and territory of North Borneo to the Republic of the Philippines

September 11, 1962

President Diosdado Macapagal issues special authorization in favor of Vice President Emmanuel Pelaez to formally accept, on behalf of the Republic of the Philippines, the cession or transfer of sovereignty over the territory of North Borneo by Sultan Mohammad Esmail Kiram, Sultan of Sulu.[79]

September 12, 1962

Heirs of the Sultan of Sulu cede all rights, proprietary, title, dominion and sovereignty to the Republic of the Philippines

Secretary of Foreign Affairs sends Note to British Ambassador asserting that the Philippine claim subsists despite the London agreements including North Borneo in the Federation of Malaysia[80]

September 27, 1962

Vice-President Emmanuel Pelaez addresses the United Nations General Assembly

We stand on what we consider to be valid legal and historical grounds. Our claim has been put forward with sincere assurance of our desire that the issue be settled by peaceful means, and without prejudice to the exercise of the right of self-determination by the inhabitants of North Borneo, preferably under United Nations auspices.[81]

December 29, 1962

Joint UK-PHL Statement after consultations.

The Philippine and British Governments being vitally concerned in the security and stability of South East Asia, have decided to hold conversations about questions and problems of mutual interest. The British Government have responded to the Philippine Government’s desire for talks, first expressed in their note of June 22, by inviting the Philippine Government to send a delegation to London for consultations at a mutually convenient date in January, 1963. Recent developments have made such conversations, in the spirit of the Manila Treaty (SEATO) and the Pacific Charter (U.N.), highly desirable.[82]

January 26, 1963

Indonesian President Sukarno pledges support to the Philippines[83]

January 28, 1963

President Macapagal restates Philippine position on Sabah in his SONA:

The situation is that the Philippines not only has a valid and historic claim to North Borneo. In addition, the pursuit of the claim is itself vital to our national security.[84]

January 28 – February 1, 1963

Talks between British and Philippine Governments held in London. See Opening Statement by Vice-President Pelaez.

Philippines panel composed of Vice President and Foreign Affairs Secretary Pelaez, Usec. Salvador P. Lopez, Defense Secretary Macario Peralta, Justice Secretary Juan Liwag, Senator Raul Manglapus, Rep. Jovito Salonga and Godofredo Ramos, and Amb. Eduardo Quintero.[85]

February 1, 1963

Joint Final Communique issued by the Philippines and the United Kingdom stating both their claims[86]

March 25, 1963

Senator Sumulong dissented to the filing of the Philippine claim to Sabah. Suggested voluntarily relinquishing whatever claims of sovereignty.

Sumulong says the claim was “tardily presented to the United Nations.” He pointed out that our claim did not specify the particular portion of North Borneo covered by it.[87]

March 30, 1963

Rep. Salonga (Rizal) responds to Senator Sumulong

Claim is of the entire Republic based on respect for the rule of law, the sanctity of contractual obligations, the sacredness of facts, and the relentless logic of our situation in this part of the world.[88]

June 7 – 11, 1963

Discussion between the foreign affairs secretaries of the Federation of Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

The meeting resulted in the drafting of the Manila Accord.[89]

July 9, 1963

Malaysia Agreement was signed.

Article I provided for the creation of the Federation of Malaysia which included the colonies of Singapore, North Borneo, and Sarawak.[90]

July 30 – August 5, 1963

MAPHILINDO (Malaya, Philippines, Indonesia) is formed, a loose consultative body among the three countries.

July 31, 1963

Manila Accord is signed

Indonesia, the Federation of Malaya, and the Philippines sign a policy statement agreeing to peacefully resolve the issue on North Borneo.

Ministers of the country agree to the creation of Malaysia with the support of the people of North Borneo to be ascertained by an independent body. (UN Secretary General)[91]

August 5, 1963

Joint Statement by the Philippines, the Federation of Malaya, and Indonesia

The United Nations Secretary-General or his representative should ascertain prior to the establishment of the Federation of Malaysia the wishes of the people of Sabah (North Borneo) and Sarawak within the context of General Assembly

A joint communiqué was issued by the foreign ministers of Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines stating that the inclusion of North Borneo in the Federation of Malaysia “would not prejudice either the Philippine claim or any right thereunder.”[92]

August 5, 1963

Foreign Affairs Secretary Salvador P. Lopez tries to get British Government to enter into a special arrangement to refer the dispute to the International Court of Justice[93]

September 9, 1963

British reply, “in view of the July 9 Agreement signed by Britain, Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore concerning establishment of the Federation of Malaysia.”[94]

September 16, 1963

Federation of Malaysia came into being as a sovereign state, with North Borneo as one of the component states.

Since the new State of Malaysia succeeded to the interests of the British Crown in Sabah, the Philippine claim had to be pursued against Malaysia.[95]

President Diosdado Macapagal, after conferring with congressional leaders and foreign policy advisers, decided to withhold recognition of the federation until the Philippines gets formal assurances that the new Malaysia would uphold the Manila accord.[96]

September 17, 1963

Philippines refused to recognize Malaysia.

Both the Philippines and Indonesia rejected the UN findings and broke off diplomatic relations with Kuala Lumpur.[97]

1963

Referendum is conducted in North Borneo. People of North Borneo choose to join Malaysia[98]

January 11, 1964

Sukarno-Macapagal Joint Statement[99]

February 5 – 10, 1964

Attempts of allies (including the U.S.A.) to mediate among the three MAPHILINDO countries result in a series of talks in Bangkok[100]

February 1964

Macapagal and Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Raman met in Phnom Penh. As a result, Tunku agreed to elevate the Sabah dispute to the World Court if he could get the Sabah leaders to go along.[101]

March 3-6, 1964

Attempts of allies (including the U.S.A.) to mediate among the three MAPHILINDO countries result in a series of talks in Tokyo[102]

May 18, 1964

Establishment of Philippine-Malaysia Diplomatic Relations by the creation of a Consulate in Kuala Lumpur.

November 19, 1964

A proposal was made by the Philippines to submit the dispute to the International Court of Justice as a token of their adherence to the rule of law and the UN Charter.[103]

August 9, 1965

Singapore is expelled from the Federation of Malaysia

June 3, 1966

Malaysia reiterates its willingness to abide by the Manila Accord and the Joint Statement of August 5, 1963[104]

1967

Plan to destabilize North Borneo (Sabah) was made by President Ferdinand Marcos.

August 8, 1967

Establishment of ASEAN[105]

August – December 1967

The Jabidah unit trains for their mission to destabilize North Borneo (Sabah)

December 30, 1967

135 of the 180 trainees of Jabidah are brought to Corregidor for “Special Training”

March 18, 1968

Jabidah Massacre

March 28, 1968

Jabidah Expose in a privilege speech of Senator Benigno S. Aquino Jr.

March 27, 1968

Constancio B. Maglana delivered a privilege speech in the House of Representatives on the Philippine claim on Sabah

Constancio B. Maglana, a member of the House of Representatives published Sabah is Philippines (1969), and in a privilege speech, apart from laying the basis for the Philippine claim, also advocated the prosecution of the claim. [106]

March 29,1968

Senate Minority Floor Leader Ambrosio Padilla reveals a document dated February 1, 1968, which was a power of attorney executed by the heirs of the Sultan of Sulu in favor of President Marcos, recognizing the authority and power of the President to represent them in the settlement of their proprietary rights over Sabah.[107]

Press Secretary Jose Aspiras announced that the authority had been given to the President as Chief Executive[108]

Malacañang released another document, also dated February 1, 1968, in which the President Ferdinand Marcos transferred to Foreign Affairs Secretary Narciso Ramos, in his official capacity, the authority conferred by the heirs of the President.[109]

June 17, 1968

Talks between the Philippines and Malaysia opened in Bangkok

Philippine panel composition: Ambassador Gauttier Bisnar, Amb. Eduardo Quintero, Dr. Florentino Feliciano,

Amb. Leon Ma. Guerrero and Amb. Mauro Caluigo

(Philippine Ambassador to Malaysia)

Delegation’s Term of Reference: Only one mode of settlement – elevating the dispute to the World Court.[110]

July 15, 1968

Malaysia rejects Philippine claim.

The position of my Government is that the Philippines has no claim at all, that there is nothing to settle, and that there is nothing more to talk about.[111]

July 16, 1968

Amb. Guerrero responds to Malaysian rejection

Says the Malaysian Ambassador’s “unipersonal rejection” has “single-handedly brought our two countries to the most serious crisis in their relations.”[112]

July 20, 1968

Upon advice of the Foreign Policy Council, President Ferdinand E. Marcos breaks diplomatic relations with Malaysia[113]

July 21, 1968

President Ferdinand E. Marcos issued a policy statements about the Philippine claim

In radio-television chat, a day after the withdrawal of diplomatic corps in Kuala Lumpur, President Ferdinand E. Marcos, reiterated the Philippine government pacific policy in its efforts to pursue the claim and advocated the recourse to filing the case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ).[114]

August 28, 1968

Congress approves Senate Bill No. 954 that delinates the baselines of the Philippines and provides that “the territory of Sabah, situated in North Borneo, over which the Republic of the Philippines has acquired dominion and sovereignty.”

Sent to the President for approval.[115]

Admiral Michael Carver, Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in the Far East said his troops, ships and planes “stand squarely behind Malaysia in the growing crises with the Philippines over Northern Sabah.”[116]

September 18, 1968

Upon the recommendation of the Foreign Policy Council, President Marcos signs Senate Bill No. 954. It became Republic Act No. 5446.[117]

US State Department Press Officer Robert J. McCloskey said the U.S. recognized the ownership of Malaysia over Sabah

Reactions:

Senator Roy: “a sneak betrayal of a friend and ally.”

Senator Benigno S. Aquino Jr: disappointment over Washington’s “shabby and painful treatment” of the Philippines.

Senator Ziga: U.S. action would make it lose friends in the Philippines[118]

Marcos called U.S. Ambassador R.G. Mennen Williams and secured assurance that U.S. would abide by her treaty commitment to defend the Philippines in case of British or Malaysian attack.

1,000 students from the University of Malaya invaded the compound of the Philippine embassy in Kuala Lumpur.

They stoned the building, pulled down the Philippine flag from its pole and trampled upon it[119]

October 15, 1968

23rd Session of the UN General Assembly, the Philippines and Malaysia tangled in a debate on the North Borneo (Sabah) Issue

PHL policy statement: bring issue up to World Court, consistent with the Manila Accord agreement

Malaysia policy statement: the people of Sabah had shown their desire to be with the Federation of Malaysia; upheld the British title to Sabah based on, “continuous occupation, administration and exercise of sovereignty, which by itself in international law, is sufficient as a good title;” there is no Philippine claim therefore nothing to discuss.[120]

December 1968

Malaysia proposed that the Philippines recognize her sovereignty over Sabah as a condition for the normalization of Philippine-Malaysian diplomatic relations, without prejudice to the Philippines pursuing her claim.[121]

January 22, 1969

President Ferdinand E. Marcos declares in SONA: Philippine claim to North Borneo is justified based on legal, historical, and moral grounds:

We will pursue the claim peacefully in keeping with the spirit of previous understandings with Malaysia and in accordance with the principles of national law. The claim is in the national interest and we intend to pursue it by making use of all available peaceful resources. We are encouraged by the fact that many of our Asian friends are helping in the search for a modus vivendi between the Philippines and Malaysia.

December 1969

Diplomatic relations between Malaysia and the Philippines formally resume as a result of a discussion between PM Tunku Abdul Rahman and Secretary of Foreign Affairs Carlos P. Romulo.

September 23, 1972

Martial Law is declared

October 24, 1972

Moro National Liberation Front begins rebellion against the government

1973 Constitution

Article on National Territory reads:

The national territory comprises the Philippine archipelago, with all the islands and waters embraced therein, and all the other territories belonging to the Philippines by historic or legal title, including the territorial sea, the air space, the subsoil, the sea-bed, the insular shelves, and the submarine areas over which the Philippines has sovereignty or jurisdiction. The waters around, between, and connecting the islands of the archipelago, irrespective of their breadth and dimensions, form part of the internal waters of the Philippines.

1974-1986

Mahakuttah Kiram becomes Sultan in 1974, after the death of his father, Sultan Esmail Kiram I. He rules until his death in 1986.

May 10, 1974

Memorandum Order No. 427, s. 1974

Creating a committee to handle the confirmation of the Sultan of Sulu by the Ruma Bechara

May 13, 1974

Executive Order No. 429, S. 1974

Creating a Consultative Council on Muslim Affairs

December 23, 1976

Tripoli agreement is signed

August 4, 1977

President Ferdinand E. Marcos gives up claim to Sabah. At this point in Marcos’ Presidency, a legislature has not yet been convened, therefore, President Marcos exercised full authority over Foreign Affairs policy.

In a speech Marcos said:

The Philippine government is taking definite steps to eliminate one of the burdens of ASEAN — the Philippine claim to Sabah.[122]

After the statement, Marcos handed draft of the “Border Crossing and Joint Patrol Agreement” to Malaysia. It was not signed.[123]

Malaysians asked two things of the Philippines:

1) 1973 Constitution with its broad definition of our national territory be amended in order to eliminate the clause, “territories belonging to the Philippines by historic right or legal title.”

2) That R.A. 5446, particularly Section 2, be repealed.[124]

June 25, 1980

At the ASEAN Foreign Ministers Conference in Kuala Lumpur, MP Arturo Tolentino declared that the Philippine claim to Sabah “…is closed. We are not raising it anymore.”[125]

Three rounds of talks between Manila and Kuala Lumpur break down with Malaysia objecting to quid pro quo approach of the Philippines.

Usec. of Foreign Affairs Pacifico Castro and Tan Sri Zainal meet intermittently in Manila and Kuala Lumpur.[126]

1982-1985

Secret talks between Minister Roberto V. Ongpin and Malaysian PM Mahathir.[127]

November 1982

Malaysian foreign ministry said, “Just a verbal announcement of the Philippines that it has dropped the claim is not enough. The Philippines has not taken all the necessary steps to delete a clause in its Constitution laying claim to Sabah.”[128]

PM Mahathir reiterated need for PHL to drop claim in a brief interview after speaking before the ASEAN Law Association general assembly at the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur.

He said claim remained a “thorny problem” even though the Philippines is not actively pursuing it.[129]

May 1, 1986

Vice President and Minister for Foreign Affairs Salvador H. Laurel meets with PM Mahathir and Foreign Minister Tengku Ahmad Rithauddeen in Kuala Lumpur

Mahatir reiterated commitment to settle proprietary issue of the heirs of the Sultan when they could agree on a single spokesperson with whom the Malaysian government could deal.

June 1986

ASEAN Foreign Ministers meeting in Manila

Usec. of Foreign Affairs Jose D. Ingles and Sec. Gen. of Malaysian Foreign Ministry continue discussion of Sabah question.[130]

July 3, 1986

Debates of the Constitutional Commission

Draft proposed by Fr. Joaquin Bernas,S.J., removes “Historical right or legal title” from the National Territory section of the Constitution and replacing it with, “Over which the Government exercises Sovereignty and Jurisdiction”

Commissioner Serafin Guingona objects to this proposal saying it might be interpreted as a dropping of our claim to Sabah.

Bernas says this was in order to adhere to generally accepted principles of international law.

July 7, 1986

Debates of the Constitutional Commission

On second Reading the provision of National Territory which states “Over which the Government exercises Sovereign Jurisdiction” is approved.

July 9, 1986

Debates of the Constitutional Commission

On Third Reading the provision of National Territory which states “Over which the Government exercises Sovereign Jurisdiction” is lost.

July 10, 1986

Debates of the Constitutional Commission

Concepcion objects to the proposed section on National Territory thus bringing it back to Second Reading.

Bernas proposes to change the word Exercises to has.

The Provision is approved.

February 16, 1987

1987 Constitution comes into full force and effect, in fulfilment of the first stipulation of the Malaysians.

The national territory comprises the Philippine archipelago, with all the islands and waters embraced therein, and all other territories over which the Philippines has sovereignty or jurisdiction, consisting of its terrestrial, fluvial and aerial domains, including its territorial sea, the seabed, the subsoil, the insular shelves, and other submarine areas. The waters around, between, and connecting the islands of the archipelago, regardless of their breadth and dimensions, form part of the internal waters of the Philippines.

February 20, 1987

Series of meetings between Usec. of Foreign Affairs Jose D. Ingles and Tan Sri Zainal held further talks in Kuala Lumpur

Usec. of Foreign Affairs Jose D. Ingles and Sec. Gen. of Malaysian Foreign Ministry continue discussion of Sabah question.[131]

June 27, 1987

Series of meetings between Usec. of Foreign Affairs Jose D. Ingles and Tan Sri Zainal held further talks in Hong Kong

Usec. of Foreign Affairs Jose D. Ingles and Sec. Gen. of Malaysian Foreign Ministry continue discussion of Sabah question. Philippines agreed to adopt new baseline law: Malaysians proposed agreements on border crossing, extradition, Treaty of Friendship, and establishment of consulates.[132]

October 23, 1987

Upon instructions from President Corazon C. Aquino, Secretary of Foreign Affairs Raul S. Manglapus tries to unify the heirs to the sultanate.

Letter of Manglapus to Senator Santanina Rasul:

I would like to suggest that the claimants organize themselves so that they may arrive at a common position…. Although yours is a private claim, we have the assurance of the Malaysian government that they are ready and willing to negotiate with the heirs of the Sultan of Sulu in order to settle this matter.

Senator Rasul successfully brings the heirs to Malacañan Palace and appoint representatives. However, talks were stalled when Jamalul III dissented.[133]

November 19, 1987

Senator Leticia Ramos-Shahani files Senate Bill no. 206 to repeal R.A. No. 5446. Says a package of bilateral treaties agreements on amity and economic cooperation, extradition, and border-crossing and patrols, are part of a package deal offered in exchange for the dropping of the Sabah claim.

Certified urgent by President Corazon C. Aquino but faced stiff opposition. It was not passed in the 8th Congress.[134]

December 4-6, 1987

President Corazon C. Aquino and Secretary Raul S. Manglapus met with the heirs without Jamalul Kiram III

Brief from the meeting:

They were of the opinion that Sultan Mohamad Jamalul Kiram III was expressing his own personal views which contravene the consensus reached at the meeting of the heirs with Secretary… Manglapus at the PICC on Friday, December 4 and at the conference of the heirs held with President Corazon C. Aquino at Malacañang on Saturday, December 5.[135]

August 28, 1988

Former Senator Arturo Tolentino opposed the Shahani Bill as it would drop Sabah claim.[136]

February 12, 1989

Sultan Mohammad Jamalal Kiram III(one of the claimnants to the throne) revoked the resolution of August 1962 regarding the transfer of title and sovereignty to the Republic of the Philippines.[137]

January 11, 1993

President Fidel V. Ramos issues Executive Order No. 46 creating the Bipartisan Executive-Legislative Advisory Council on the Sabah Issues

January 27 – 30, 1993

President Fidel V. Ramos state visit to Malaysia.

President Fidel V. Ramos makes proposal, Malaysia agrees to set up a consulate in Sabah and Davao, respectively. Downplays North Borneo issue despite calls from members of Congress to pursue claim.

February 10, 1993

President Fidel V. Ramos attempts to unify the heirs to the Sultanate.

President Ramos suggested that to the representatives of the heirs that they create a corporation called the Sulu-Sabah Development Corporation. The entity would be the conduit of funds from the settlement of the proprietary claim over Sabah.[138]

July 1993

The Philippines and Malaysia sign MOU on Joint Commission on Bilateral Cooperation

December 6-10, 1993

1st PH-Malaysia Joint Commission for Bilateral Cooperation

The Meeting discussed the reciprocal establishment of Consular Offices in the Philippines and Malaysia.

The Philippine delegation stated that the Philippine Government was still considering possible sites for the establishment of a Consulate in East Malaysia

The Malaysian Delegation informed that Malaysia wishes to establish a consulate in southern Philippines. The Philippine Delegation welcomed the Malaysian proposal. The Philippine Delegation indicated that the Philippines is considering possible sites for a consular office in East Malaysia[139]

March 26, 1994

President Fidel V. Ramos proposes creation of BIMP-EAGA (Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Philippines-East ASEAN Growth Area)

1995, 10th Congress

HB 2657 – “The Philippine Exclusive Economic Zone Act of 1995”[140]

Introduced by Rep. Manuel B. Villar, Jr.

March 28 – 29, 1995

2nd PH-Malaysia Joint Commission for Bilateral Cooperation

The Malaysian side stated that the Malaysian Government has decided to establish a Consulate General in Davao City. A formal notification would be made to the Philippine Government and plans are for the Consulate to be set up in May/June 1995.”

The Philippine side welcomed the decision of the Malaysian Government and assured the Philippine Government’s full cooperation in the establishment of the Malaysian Consulate in Davao City. The Philippine side that the Philippine Government has yet to decide on the location of its Consulate in east Malaysia.[141]

1995

Philippine and Malaysian governments agree to setup a consulate in Sabah and Davao, respectively. Malaysia setup a consulate in Davao in December but the Philippines did not push through.[142]

May 29 – 31, 1995

3rd PH-Malaysia Joint Commission for Bilateral Cooperation (JCBC)

The Meeting agreed on the need to hold regular informal consultations between the relevant agencies of the two sides to resolve any outstanding problem pertaining to Filipino workers and illegal immigrants[143]

Opening Remarks by Datuk Abdullah Haji Ahmad Badawi, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Malaysia for the 3rd PH-Malaysia Joint Commission for Bilateral Cooperation (JCBC)

Regulating the Flow of People and Goods:

….The Armed Forces and Police of our respective countries have already concluded a historic joint patrol exercise designed to curb piracy, illegal entry and illegal fishing in the territorial waters of the two countries. A working group between our two countries had recently met in Sabah to deal with border crossing matters. This is an important development which will contribute to facilitating and regulating the flow of people and goods at the border areas of East Malaysia and Southern Philippines…..[144]

1996

Princess Denchurain Kiram writes Prime Minister Mahatir of Malaysia asking to increase the rental $1,000,000. She also said that she is willing to renounce the claim if the Malaysian Government provide a fair settlement.

Proposal was refused by the Prime Minister.[145]

September 2, 1996

Peace agreement MNLF

December 1996

Border Crossing and Joint Patrol agreements signed by the Philippines and Malaysia.

1998, 11th Congress

HB 2973 – “Archipelagic Baselines Law of the Philippines”

Introduced by Hon. J. Apolinario L. Lozada, Jr.[146]

July 5, 1999

Executive Order No. 117 reconstituted the Bipartisan Executive-Legislative Advisory Council on the Sabah Issues

12th Congress

HB 2031 (HB 2973 re-filed)

Introduced by Hon. J. Apolinario L. Lozada, Jr.[147]

March 1-3, 2000

4th Malaysia-PH Joint Commission for Bilateral Cooperation

Establishment of a Consulate in Sabah:

The Meeting noted Philippines’ commitment towards the establishment of a Philippine Consulate in Sabah.[148]

January 2001

Sultan Esmail Kiram II writes Prime Minister Mahathir, through President Gloria Macapagal- Arroyo to increase the lease fee to $855 million per annum[149]

February 2001

PHL files for Application to Gain Access to the Pleadings at the International Court of Justice hearing on the Ligitan-Sipadan islands dispute between Malaysia and Indonesia in order “to preserve and safeguard its historical and legal rights arising from its claim to sovereignty and dominion over the territory of North Borneo.”

March 13, 2001

PHL petitions ICJ to intervene in territorial dispute over Sipadan and Ligitan islands between Malaysia and Indonesia

March 14, 2001

Malaysian authorities reportedly expressed willingness to buy Sabah for US $800 M

Deal supposedly initiated by heirs of the Sultan of Sulu through legal counsel Ulka Ulama[150]

August 9, 2001

President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, upon her return from a state visit to Malaysia, asks Vice President and Foreign Affairs Secretary Teofisto Guingona to set up an economic and cultural office in Sabah.

Office would be similar to Manila Economic and Cultural Office in Taiwan[151]

October 24, 2001

ICJ denies application of Philippines for intervention.

November 2001

ARMM Governor Nur Misuari ordered his troops to wage rebellion. He escapes to Malaysia. Malaysian government extradites him back to the Philippines

Misuari, ARMM Governor since 1996, tried to lobby for an extension of his term set to expire in 2002. Failing, he ordered the Moro National Liberation Front to rebel in Jolo. It is crushed.[152]

2002

Some of the heirs meet in Malacañan Palace at the invitation of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.

According to the article, Jamalul Kiram III was recognized as the Sultan. President Arroyo sent the letter asking for the adjustment of rent to Sabah to the Malaysian Prime Minister[153]

September 6, 2002

Executive Order No. 121 again reconstituted the Bipartisan Executive-Legislative Advisory Council on the Sabah Issues

September 19, 2002

President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo assures heirs of Sultan of Sulu that they are protected.

August 2002

Reports of “heavy-handed” of Filipino deportees spark diplomatic protest from Manila.

Philippine lawmakers support revival of claim.

President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo urges officials and the public to separate territorial dispute from issue of Filipino deportees.

13th Congress

HB 1973 – An act defining the archipelagic baselines of the Philippine archipelago to include the Kalayaan Island Group and to conform with the provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, amending for the purpose Republic Act No. 3046, as amended by Republic Act No. 5446.

Introduced by Hon. Antonio V. Cuenco[154]

HB 6087 – An act defining the archipelagic baselines of the Philippine archipelago, amending for the purpose Republic Act No. 3046, as amended by Republic Act No. 5446.

Introduced by the Hons. Antonio V. Cuenco, Edgardo M. Chatto, Carmen L. Cari, Jose G. Solis and Roilo S. Golez[155]

July 14-16, 2004

JCBC discusses Filipino workers in Sabah and proposes Philippines set up a consulate in Sabah.

The Malaysian side requested the Philippine side to establish a Consulate in Sabah as soon as possible. The Philippine side reiterated the government’s commitment on this matter.[156]

September 14, 2004

Executive Order No. 357 The Bipartisan Executive-Legislative Advisory Council on the Sabah Issues was abolished and its functions transferred to DFA

September 2005

Group calling itself the “Royal Sultanate of Sulu Archipelago’s Supreme Council” warned Malaysian government not to entertain claims forwarded to it by so-called Sultan Rodinood Julaspi Kiram regarding the resolution of the North Borneo territorial issue.

April 27-28 2006

Closing Statement of Malaysian Foreign Minister Dato’ Seri Syed Hamid Albar at the 6th Malaysia-PH Joint Commission Meeting

Malaysian Foreign Minister Dato’ Seri Syed Hamid Albar, in his closing statement during the 6th Malaysia-PH Joint Commission Meeting in Kuala Lumpur, asked Secretary Alberto G. Romulo to jointly “find ways to bring a final conclusion to the long due bilateral matters, namely the displaced people in Sabah and the setting up of the Philippine Consulate General in Kota Kinabalu.”[157]

June 3, 2006

Mohammad Fuad Abdulla Kiram I was proclaimed 35th Sultan of the Royal Hashimite Sultanate of Sulu and Sabah with a backing of the Moro National Liberation Front.

May 2007

Jamalul Kiram III runs unsuccessfully for Senator under Partido Demokratikong Sosyalista ng Pilipinas (PDSP), receiving over two million votes. PDSP coalesces with President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s Lakas-CMD and KAMPI to form TEAM Unity. Administration coalition is crushed in the polls with only two of its bets winning, the other 10 seats are won by the opposition.

14th Congress

HB 1202[158]

Introduced by Hon. Antonio V. Cuenco

May 29, 2008

Nur Misuari called for the revival of North Borneo claim in Second Mindanao Leadership Summit attended by MNLF combatants

Strong reaction from Datuk Seri Panglima Yong Teck Lee, President of the Sabah Progressive Party urging Malaysia’s Federal Government to bring in military, set up consulates in Mindanao and invite PHL to set up consulate in Sabah

July 9, 2008

“Sultanate of Sulu” reportedly starts issuing birth certificates to Filipinos in Sabah

July 27, 2008

Datu Omar negotiator of Mohammad Jamal Al Alam heirs was quoted “obtained signatures of nine heirs relinquishing claims to Sabah” but these are denied by claimants

Uka Ulama claimed that nobody has the power to drop the claim because there is no more Sultan who reigns and rules over the territory.

August 10, 2008

Sulu provincial government tells Malaysia to Increase annual payment to Jamalul Kiram III to $500M[159]

August 20, 2008

President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo issues Memorandum Circular No. 162 or “Guidelines on matters pertaining to North Borneo (Sabah)”

No recognition of a foreign state’s sovereignty over North Borneo; any official activity relating to North Borneo carried out only with the clearance of or after consultations with DFA

March 10, 2009

President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo signs R.A. 9522, amending R.A. 5446

In fulfilment of the second Malaysian stipulation, President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo removes mention of Sabah or North Borneo in the Archipelagic Baselines of the Philippines law

2010

Nur Misuari issued a statement calling the attention of Malaysia to settle the Sabah issue.[160]

June 2010

Sulu provincial board passed a resolution supporting the demand of heirs to increase the yearly payment to at least $500 Million. [161]

July 16, 2011

Supreme Court decision (GR No. 187167) upholds the baseline law

In its decision, the Supreme Court makes a conclusion of law: that R.A. 9522 did not repeal R.A. 5466, and that therefore, the Philippine claim over Sabah is retained and can be pursued. However, since this is a conclusion of law, the Supreme Court made its conclusion of law without explaining the reasons for its conclusion. It makes the decision, however, binding on the government.

April 24-27, 2012

Visit to the Philippines of Malaysian House Speaker Pandikar Amin Haji Mulia

Malaysian House Speaker Pandikar Amin Haji Mulia raised the matter of the opening of a consulate during his call on President Benigno S. Aquino III, who, in response, instructed the Secretary of Foreign Affairs to study the proposal.[162]

June 5, 2012

Upon returning from a visit to Malaysia, Vice-President Binay says he will recommend to the President the setting up of a Philippine Consulate in Sabah. (ABS-CBNNews.com)

February 12, 2013

Followers of Jamalul Kiram numbering over 200 men landed in Laha Datu village in Sabah on February 12, 2013.[163]

Graphic showing Malaysia’s Sabah, where Malaysian forces are facing off with followers of a Filipino Muslim sultan who are claiming the territory as their ancestral land.

[1] Abinales, Patricio. “Re-constructing Colonial Philippines: 1900-1910.” 1900-2000: the Philippine Century. Manila: Philippines Free Press, 2001. p. 19. Print.

[2] Cesar Adib Majul: “Muslims in the Philippines,” 1999 edition

[3] Treacher, W.H. . British Borneo: Sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo.Singapore: Government Printing Department, 1891. Print.

[4] Abinales, Patricio. “Re-constructing Colonial Philippines: 1900-1910.” 1900-2000: the Philippine Century. Manila: Philippines Free Press, 2001. p. 19. Print.

[5] Abinales, Patricio. “Re-constructing Colonial Philippines: 1900-1910.” 1900-2000: the Philippine Century. Manila: Philippines Free Press, 2001. p. 19. Print.; Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[6] Treacher, W.H. . British Borneo: Sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo.Singapore: Government Printing Department, 1891. Print.

[7] Treacher, W.H. . British Borneo: Sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo. Singapore: Government Printing Department, 1891. Print.

[8] Treacher, W.H. . British Borneo: Sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo.Singapore: Government Printing Department, 1891. Print.

[12] Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[15] Treacher, W.H. . British Borneo: Sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo. Singapore: Government Printing Department, 1891. Print.; Original Document: December 1878 Statement and Application of Debt of Dent and Overbeck to the Marquis of Salisbury

[16] Treacher, W.H. . British Borneo: Sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo. Singapore: Government Printing Department, 1891. Print.; The Philippine claim to a portion of North Borneo: materials and documents.. Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines: Institute of International Legal Studies, University of the Philippines Law Center, 2003. Print.

[17] U.P. Law Center – The Philippine Claim to a portion of North Borneo (Sabah): Materials and Documents

[18] U.P. Law Center – The Philippine Claim to a portion of North Borneo (Sabah): Materials and Documents

[19] U.P. Law Center – The Philippine Claim to a portion of North Borneo (Sabah): Materials and Documents

[20] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print. ; Treacher, W.H. . British Borneo: Sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo. Singapore: Government Printing Department, 1891. Print.

[21] Tarling, Nicholas. The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia (Volume Two, Part One). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Print.

[22] U.P. Law Center – The Philippine Claim to a portion of North Borneo (Sabah): Materials and Documents

[23] Treacher, W.H. . British Borneo: Sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo. Singapore: Government Printing Department, 1891. Print.; Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[24] Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[25] The Philippine claim to a portion of North Borneo: materials and documents.. Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines: Institute of International Legal Studies, University of the Philippines Law Center, 2003. Print.

[26] Treacher, W.H. . British Borneo: Sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo.Singapore: Government Printing Department, 1891. Print.

[27] Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[28] Treacher, W.H. . British Borneo: Sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo. Singapore: Government Printing Department, 1891. Print.

[29] Treacher, W.H. . British Borneo: Sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo.Singapore: Government Printing Department, 1891. Print.

[30] Tarling, Nicholas. The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia (Volume Two, Part One). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Print.

[31] Bautista Lowell B. “The Historical Context and Legal Basis of the

Philippine Treaty Limits” Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal. 2008

[32] Agoncillo, Teodoro A.. Malolos: the crisis of the Republic. Quezon City: University of the Philippines, 1960. Print.

[33] Bautista Lowell B. “The Historical Context and Legal Basis of the

Philippine Treaty Limits” Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal. 2008

[34] Bautista Lowell B. “The Historical Context and Legal Basis of the

Philippine Treaty Limits” Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal. 2008

[35] Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[36] Letter of Diosdado Macapagal to Sen. Leticia Ramos-Shahani dated

May 1, 1989

[37] Harrison, Francis Burton. The Cornerstone of Philippine Independence, A Narrative of Seven Years. 1922. Reprint. Michigan: UMI Books on Demand, 2002. Print

[38] Letter of Diosdado Macapagal to Sen. Leticia Ramos-Shahani dated

May 1, 1989

[39] Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[40] Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[41] Fry, Howard T. “The Bacon Bill of 1926: New Light on an Exercise in Divide-and-Rule” Philippine Studies Journal. 1978; Churchill, Bernardita R. The Philippine Independence Missions to the United States 1919-1934 (1983 NHI)

[42] Bautista Lowell B. “The Historical Context and Legal Basis of the

Philippine Treaty Limits” Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal. 2008

[43] The Sunday Times, 9 May 1937 p. 10

[44] Harrison, Francis Burton. The Cornerstone of Philippine Independence, A Narrative of Seven Years. 1922. Reprint. Michigan: UMI Books on Demand, 2002. Print

[45] Philippine Magazine Volume XXXIV No.3 (March 1937)

[46] Philippine Magazine Volume XXXIV No.3 (March 1937)

[47] Sunday Times, May 9, 1937

[48] Sunday Times Article, May 9, 1937

[49] Memorandum of President Manuel L. Quezon

[50] Original Document: Letter of Rep. Amilbangsa to President Manuel L. Quezon

[51] Original Document: Manuel L. Quezon letter to Executive Secretary Jorge Vargas

[52] Newspaper article: Sydney Morning Herald; Original Document: Harrison letter to Vice President Elpidio Quirino dated February 27, 1947

[53] United Press Article, 1940

[54] Tarling, Nicholas. The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia (Volume Two, Part Two).Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Print.

[55] Parpan S.J., Alfredo G. “The Philippine Claim on North Borneo: Another Look” Philippine Studies. (1988) Print.

[56] Parpan S.J., Alfredo G. “The Philippine Claim on North Borneo: Another Look” Philippine Studies. (1988) Print.; Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[57] Macapagal, Diosdado. “A Stone for the Edifice, Memoirs of a President” (1968); Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[58] Original Document: Harrison letter to Vice President Elpidio Quirino dated February 27, 1947

[59] Original Document: Harrison letter to Vice President Elpidio Quirino dated February 27, 1947

[60] Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[61] Tarling, Nicholas. The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia (Volume Two, Part Two).Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Print.

[62] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print.

[63] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print.

[64] Milton Walter Mayer. A Diplomatic History of the Philippine Republic: The First Years 1946-1961.

[65] Milton Walter Mayer. A Diplomatic History of the Philippine Republic: The First Years 1946-1961.

[66] Original Document: Federation of Malaya Act

[67] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print.

[68] Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[69] Original Document: Federation of Malaya Independence Act

[70] Fernandez, Erwin S., Philippine-Malaysia Dispute over Sabah: A Bibliographic Survey. Department of Filipino and Philippine Literature, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Vol.7 No. 2, December 2007

[71] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print.; Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[72] U.P. Law Center – The Philippine Claim to a portion of North Borneo (Sabah): Materials and Documents

[73] The Philippine claim to a portion of North Borneo: materials and documents.. Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines: Institute of International Legal Studies, University of the Philippines Law Center, 2003. Print.

[74] The Philippine claim to a portion of North Borneo: materials and documents.. Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines: Institute of International Legal Studies, University of the Philippines Law Center, 2003. Print.; DFA. “A Study on the Claim to North Borneo (Sabah).”

[75] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print.

[76] The Philippine Claim to a portion of North Borneo: Materials and Documents; Macapagal, Diosdado. “A Stone for the Edifice, Memoirs of a President” (1968);

[77] Macapagal, Diosdado. “A Stone for the Edifice, Memoirs of a President” (1968);Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. (Print.)

[78] The Philippine Claim to a portion of North Borneo: Materials and Documents

[79] The Philippine claim to a portion of North Borneo: materials and documents.. Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines: Institute of International Legal Studies, University of the Philippines Law Center, 2003. Print.

[80] The Philippine claim to a portion of North Borneo: materials and documents.. Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines: Institute of International Legal Studies, University of the Philippines Law Center, 2003. Print.

[81] Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.

[82] Ortiz, Pacifico . “Legal Aspects of the North Borneo Question.” Philippine Studies. 11.1 (1963): 18-64. Print.; The Philippine claim to a portion of North Borneo: materials and documents.. Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines: Institute of International Legal Studies, University of the Philippines Law Center, 2003. Print.

[83] Macapagal, Diosdado. “A Stone for the Edifice, Memoirs of a President” (1968);

[84] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print.

[85] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print.

[86] The Philippine Claim to a portion of North Borneo: Materials and Documents..Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines: Institute of International Legal Studies, University of the Philippines Law Center, 2003. Print.

[87] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print.

[88] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print.

[89] Philippine Claim to Sabah (North Borneo) Vol. II

[90] Original Document: Agreement relating to Malaysia, 1963

[91] Original Document: Manila Accord sign on July 31, 1963 by President Soekarno, President Macapagal, and Prime Minister Tunku.

[92] Original Document: Joint Statement of the Philippines, Federation of Malaya, and Indonesia

[93] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print.

[94] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print.

[95] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print.

[96] Jose, Abueva, and de Guzaman Raul.Foundations and Dynamics of the Filipino Government and Politics. Quezon City: Bookmark, 1969. Print.

[97] Parpan S.J., Alfredo G. “The Philippine Claim on North Borneo: Another Look” Philippine Studies. (1988) Print.; Jose, Abueva, and de Guzaman Raul.Foundations and Dynamics of the Filipino Government and Politics. Quezon City:

[98] Severino, Rodolfo. Where in the World Is the Philippines?: Debating Its National Territory(2011); Flores, Jeremia C. et. al. “The Legal Implications of the Unilateral Dropping of the Sabah Claim”Philippine Law Journal. (1982)

[99] Macapagal, Diosdado. “A Stone for the Edifice, Memoirs of a President” (1968);

[100] Parpan S.J., Alfredo G. “The Philippine Claim on North Borneo: Another Look” Philippine Studies. (1988) Print.,

[101] Tolentino, Arturo M. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Pub. House, 1990. Print.

[102] Parpan S.J., Alfredo G. “The Philippine Claim on North Borneo: Another Look” Philippine Studies. (1988) Print.,

[103] Parpan S.J., Alfredo G. “The Philippine Claim on North Borneo: Another Look” Philippine Studies. (1988) Print.,