The man who would be king

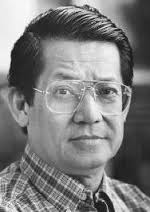

NEW YORK, New York —Thirty-one years ago, on August 21, 1983, Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. was murdered on the tarmac of the Manila International Airport, the victim of the Marcos regime. He left behind a widow, Corazon Cojuangco Aquino, who would succeed Marcos as head of the republic; and, among other children, a son, Benigno III, who now sits as a one-term president.

In 1980 after heart surgery in Texas, he and his family lived in comfortable exile in Boston, which included a teaching stint at Harvard. Three years later, he decided to return on a deadly fool’s errand: to try and convince an ailing dictator to agree to a peaceful transfer of power. Marcos’ deteriorating health was an open secret. Suffering from lupus erythematosus, a kidney disorder, he required regular dialysis. Which meant there were times when he was not in charge, and Aquino feared a bloody power struggle when the disease finally felled the dictator.

As befits a cloak-and-dagger scenario, he had flown under a pseudonym—Marcial Bonifacio, an allusion to martial law and Ft. Bonifacio, where he had been imprisoned—and took a circuitous route to get to Manila. But the whole world seemed to know, certainly the crowds that thronged the airport to greet him, and the regime’s security forces. The bulletproof vest he donned could not of course prevent a bullet to the head. He had prepared himself for this. Prior to his return, Aquino had declared prophetically, “The Filipino is worth dying for.”

The assassination in broad daylight, of the regime’s most famous opposition senator, was immediately blamed on a petty hoodlum, Rolando Galman, killed, conveniently, on the spot. Not for a second did anyone believe this story. Galman had absolutely no history of political ties, with either the right or the left, and therefore no motive. At the wrong place at the wrong time, he had been abducted by government soldiers to play, literally and figuratively, the fall guy.

Ninoy’s assassination proved to be the catalyst in hastening the downfall of the regime. The privileged class, to which Ninoy and his family belonged, realized that if one of theirs could be cut down brazenly, then no one, not even they, were safe. And so its coiffed and perfumed members (along with maids in tow, surely one of the more bizarre and humorous elements of street theater then) marched alongside other, more seasoned demonstrators—Makati and the street joining in an incongruous pas de deux, leading to the snap elections and the February 1986 uprising that forced the Marcoses to flee into exile, to Hawai’i, where Marcos eventually died.

I worked for The Village Voice at the time, and one of the editors asked me if wanted to write something on this murder most foul. In response, I wrote a poem “On the Assassination of Benigno Aquino.” In part, it reads: “In cold exile, a man weeps / and returns, no muscled Ulysses, / But a man still, / In search of a nobler self. But / the fatal speech of a bullet / Locks his forward step onto the / Past. No more a man, he is / Much more the man than the tyrant / who with his horrid harridan, / Quells everything that/ makes everything end well.”

I also recommended that the fictionist and fellow journalist Ninotchka Rosca, also living in New York, be asked to write a piece. The paper did, and she did. Her commentary was titled “Endgame in Manila.” Of the killing, she wrote: “Never underestimate the force of megalomania. Ninoy’s murder was meant as a message: the Philippines was Marcos country and none could set foot in it against his wishes. With one bullet, an effective challenge to Marcos’ partnership with the U.S. was removed and American strategic interests were tied to his regime. There would be no turning back. Maccoy was holding hostage a country of 50 million.”

The Agrava Commission, set up to investigate the killing, in its majority findings indicted generals Fabian Ver, Luther Custodio, and Prospero Olivas. A subsequent 1985 trial before the Sandiganbayan, or special court, resulted in the acquittal of all the accused, roundly denounced as a travesty of justice. With the fall of the Marcoses in 1986 and the installation of Cory’s government, a new trial resulted in 16 members of the military being convicted of the murder not only of Aquino but also of Galman. The only high-ranking officer found guilty was General Custodio.

It’s crucial to remember Ninoy’s death not only to honor his memory, but just as importantly to remind ourselves of the kind of government the country had then. Apologists for the Marcoses, and there seem to be quite a number of them, are a reminder that historical amnesia has become a notable affliction and one that they bear rather proudly. Not surprising, of course, for so many of these suck at the breasts of privilege. And some who do remember do so differently, through almost a haze of nostalgia, with a concomitant refusal to acknowledge the myriad felonies, thievery on a grand sale, and massive human rights abuses the regime committed. And finally, there are those who benefitted from martial law; to get them to admit that the whole enterprise was morally wrong would be akin to prodding dogs that have prospered under a master’s table to bite the hand that fed them.

Had he lived to become president would Ninoy have led us to the Promised Land? The former senator Jovito Salonga said that Ninoy was “the greatest president we never had.” Ninoy certainly would have been a more effective chief executive than his widow, a saintly neophyte who oftentimes was in over her head.

As for the son, the record is a mixed one, though much better than Gloria Macapagal Arroyo’s and Joseph Estrada’s. Sure, the economy has improved but for whose benefit? Justice remains an elusive thing. With the trial for the alleged perpetrators in the 2009 Mangudadatu massacre proceeding at a glacial pace, what hope do ordinary folks have in seeing justice done in their cases? Additionally, industrialization and infrastructure continue to be neglected—areas where job creation could surely help in reducing the outflow of Filipinos seeking a better life abroad. When that exodus slows down notably, then the daan matuwid (the straight road) philosophy of Noynoy’s governance can also be the daan pauwi, or the road home.

Copyright L.H. Francia 2014