WWII veteran receives war medals 66 years late

SALT LAKE CITY — More than six decades after being freed from a Japanese prisoner of war camp, a Utah veteran was compelled to relive the horrors and triumphs of his World War II experience this month when he received a mysterious package containing seven military medals, including the Distinguished Service Cross and Silver Star.

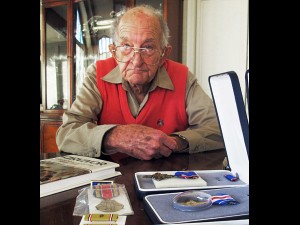

Tom Harrison, 93, displays his World War II medals at his home in Salt Lake City on Sunday. He received seven medals, including the Distinguished Service Cross and the Silver Star, six decades later. AP Photo

The medals have become a source of pride for retired Army Capt. Tom Harrison, 93, since they arrived in a box with nothing more than a packing slip from a logistics center in Philadelphia on Nov. 4, which happened to be his 65th wedding anniversary. But they have also refreshed painful memories of the Bataan Death March, Japanese prisoner-of-war camps and the comrades he lost during the war or in the years since.

Harrison can talk at length about his time as a soldier in the Philippines. But he talks about it much like he talks about golf, focusing on small details — be it the flight of a well-hit tee shot or the day he met Gen. Douglass MacArthur — and the people that surrounded him. He doesn’t dwell on his own valor.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor forced the United States into the war, Harrison spent months fighting the Japanese before American and Filipino troops surrendered at the Battle of Bataan. He eventually survived, without lasting physical injury, the Bataan Death March and three-plus years as a Japanese prisoner of war.

“It brings back memories, but also makes you feel like somebody appreciated your service,” Harrison said while sitting in his living room with the medals. “It also reminds me of the people I served with in the Philippines. I’m the only survivor from my unit now. I’ve lost most of my friends.”

About 20 years ago, Harrison “shook the cobwebs loose” on his war experiences by writing a book called “Survivor.” That has made it easier — but not easy — to talk about the suffering, the disease and the starvation that defined the years of imprisonment.

Article continues after this advertisementThe medals prompted new interest from his family about the war, Harrison said, although he is reluctant to talk at length about his personal experiences. Instead, Harrison holds up a Presidential Unit Citation as one medal he was particularly pleased to receive because it recognized the soldiers he served with and trained.

Article continues after this advertisementHis leadership and bravery earned him two of the Army’s highest honors, the Distinguished Service Cross and Silver Star. While those medals are only given for extraordinary acts of selfless valor, Harrison said he doesn’t remember — or is reluctant to explain — what he did to earn them.

“I don’t like to talk about what makes a hero. It’s not something I like to broadcast,” Harrison said. “But my kids are impressed, and my grandkids say they (the medals) are ‘awesome.'”

It hasn’t been uncommon for World War II veterans to receive medals decades later because relatively few were actually given out during or immediately following the war, said retired 1st Sgt. Dennis Meeks, a customer service manager for the South Carolina-based Medals of America, a company that works with military officials to distribute medals to veterans.

Instead, veterans were given ribbons because precious metals such as bronze and silver were needed for more pressing wartime needs, Meeks said. Additionally, a number of medals were granted in the years after service members were discharged.

That means many veterans needed to apply to receive their medals, and a strong majority of them did not.

“The Greatest Generation just put this war to the side when it ended,” Meeks said. “They had other concerns, like starting families and careers.”

As for Harrison’s medals, however, it remains a mystery as to who actually requested them. His son, Peter Harrison, said nobody in the family has taken credit for doing it, although they have celebrated the medals with a family dinner.

Army officials didn’t respond to email requests for comment and weren’t available on Friday because of the Veterans Day federal holiday.

Eventually, the medals will be displayed in Tom Harrison’s modestly decorated but spacious home, which is about 50 yards (45 meters) from the 7th hole of the Salt Lake Country Club. They will serve as reminders of a well-lived life for him, his wife and his family.

“They add excitement to an otherwise sedentary life,” he said. “I can still remember it all, even after such a long time. I don’t like to bring it up, but I’ll talk about it if asked.”