Tale of two welcomes: Imelda, Ateneo and the hero it once insulted

She looked happy in the photographs and those around her, including young scholars and the president of the Ateneo de Manila University, certainly appeared thrilled to be with her.

“Ah, Ateneo loves Imelda Marcos,” the photos said.

How different it was from the way Ateneo once welcomed one of its own, the student leader Edgar Jopson, a true blue Atenista who gave his life to fight dictatorship, and for whom the school held perhaps the most stunningly disrespectful memorial service in its history.

More on that later.

It’s a good sign that Ateneo’s warm welcome for Imelda was greeted with such vehement outrage the Jesuit university’s president, Fr. Jett Villarin was forced quickly to issue an apology.

Article continues after this advertisement“Please know that in the education of our youth, the Ateneo de Manila will never forget the Martial Law years of oppression and injustice presided over by Mr. Ferdinand Marcos,” he said. “We would not be catching up on nation building as we are today, had it not been for all that was destroyed during that terrible time … I would like to reaffirm that we have not forgotten the darkness of those years of dictatorship…”

Article continues after this advertisementAnd, in fact, the Ateneo has demonstrated in many ways that it has not forgotten.

The university’s publishing house, the Ateneo Press, has published books on the regime, including a collection of profiles of Atenistas who joined the fight against dictatorship, including Edjop. Many Ateneo students and faculty members were actively involved the movement against the Marcos regime.

But the embarrassing photo-op with Imelda, at a time when the dictator’s widow is openly bragging about Bongbong’s presidential ambitions and her desire to reclaim Malacanang, shows that the university needs to do more to remember and to not forget.

And more importantly, it needs to do more to help its own students know and understand what happened to us when the Marcoses were in power.

They could start with the stories of Atenistas who defied tyranny, like Manny Yap, the activist who was picked up by the Marcos security forces in 1976 and never seen again. Or Emmanuel Lacaba, the poet-artist who was killed by Marcos’s military that same year.

And perhaps Ateneo could reflect on its own troubling responses to Atenista activists who defied not just the regime, but also an elitist political system that made it possible for a Marcos to emerge.

Which brings us back to Edjop and the cold-hearted welcome Ateneo gave him after his death.

Edjop, a popular, nationally recognized student leader who was named one of the Ten Outstanding Young Men of 1970, joined the underground movement against Marcos after Martial Law was declared.

He was then already famous for an act of courage.

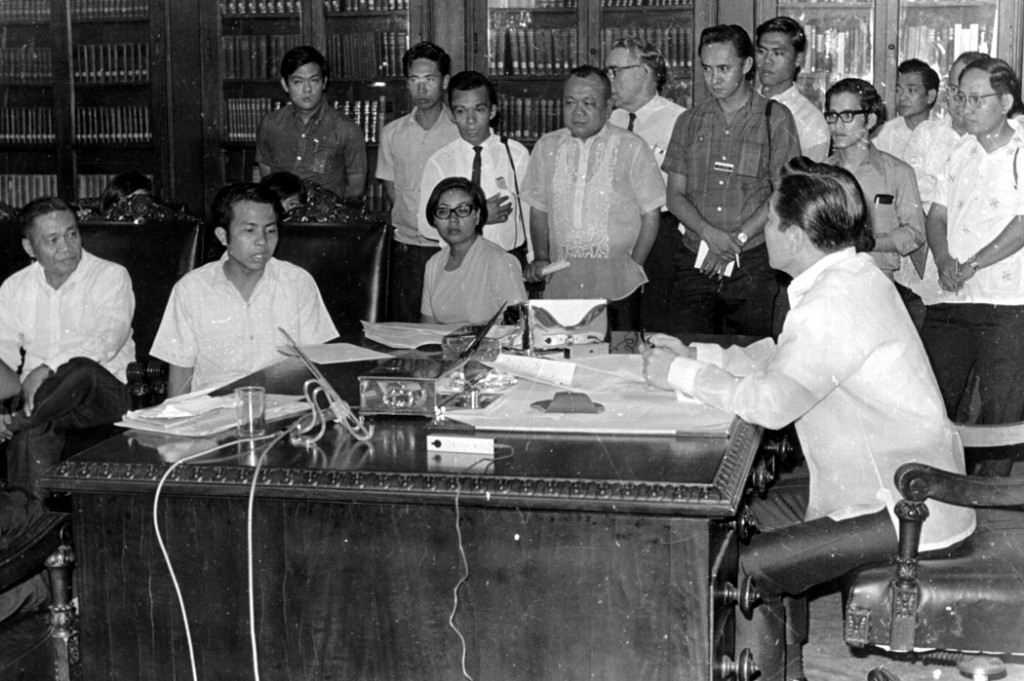

In January 1970, in a meeting with Ferdinand Marcos at Malacanang, he dared ask the president to promise in writing that he would not seek a third term. Marcos responded by insulting Edjop, dismissing him as a mere grocer’s son.

Edjop’s defiant act turned out to be prescient. For Marcos held on to power, unleashing a 14-year murderous reign of greed and brutality.

Edjop did not think twice about joining the fight against the regime, even if it meant giving up his life of privilege and comfort. A graduate of one of the country’s most prestigious universities, Edjop began life after college living with and organizing factory workers in Manila. And he kept on fighting until in 1982, he was killed in a military raid in Davao City.

His family wanted to hold a memorial service on the campus where he had spent most of his youth and where he took seriously its dictum of being a “man for others.”

But the Jesuit institution that once hailed him as the model Atenista initially refused his family’s request. The school said it was worried about military surveillance and the security of its own students.

Only after Ateneo alumni protested the school’s reluctance to honor Edjop did the university finally agree.

But it was not exactly a warm welcome, certainly not the kind that Imelda Marcos just received on the Loyola Heights campus.

No photo-ops. No selfies. No smiling school officials.

Instead, Edjop was welcomed with brazen disrespect.

The late poet, and another prominent Atenean, Freddie Salanga, later recalled what happened in a 1982 article:

“The mass over, I opted to go in and join the line queueing up for a last view of the friend in the long brown coffin. When my turn came I could hardly make him out under glass for the Jesuits had sprinkled too much holy water. As I made a turn past the altar I stopped to look back and suddenly heard this Jesuit practically pleading with the family to please decide when to close the coffin and take it out. He had a stupid smile on his face and anyone could plainly see that he was nervous. It took all I could to keep myself from pushing him away. There was still a long line of mourners and all he could think of was hustling everyone away…

“They may not have agreed with his brand of seeking justice, but the man had, undoubtedly, stood for the same thing many of them had been (sometimes triumphantly) preaching about, albeit under better protective cover, for Loyola Heights is hardly any sane man’s idea of a guerrilla jungle.”

In fact, some from the Ateneo paid tribute to his heroism.

One of them was one of his Jesuit mentors Father William Kreutz, who had coined the nickname Edjop, and who said in an interview, “Anyone who follows through and dies for what he or she believes in, especially if it’s for the benefit of the nation, I think that person deserves to be called a hero.”

The Ateneo community has since embraced that view.

But in reaffirming that it has “not forgotten the darkness of those years of dictatorship,” Ateneo could perhaps acknowledge that it once also was lost in and afraid of the dark.

Visit and like the Kuwento page on Facebook at www.facebook.com/boyingpimentel

On Twitter @boyingpimentel

RELATED STORY

Is Ateneo’s apology on Imelda Marcos’ visit enough? Netizens weigh in