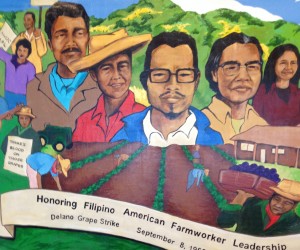

Part of the mural detail depicting Larry Itliong (with glasses, sixth from left), Cesar Chavez (seventh from left) and Dolores Huerta (seventh from left)

MILPITAS, California—Johnny Itliong, 48, choked up twice while addressing the crowd at the unveiling ceremony of the mural honoring his father and other farm workers at this city’s library auditorium last Saturday, Oct. 12.

The mural, the brainchild of San Jose State University alumni, depicts his late father, Larry Itliong, together with Cesar Chavez, Philip Vera Cruz, Pete Velasco, Dolores Huerta and other labor union members prominent in the Delano farm workers’ grape strike in 1965.

What began as a long, hard and often violent struggle for a wage increase from 75 cents to $1.25 an hour and better working conditions, captured the world’s attention. It also inspired the organized labor union movement in the US.

But until now, most of the world knows only part of the story. “My family has been hurting for so many years,” said Johnny Itliong, who works as a cook in Hollywood. “We were put aside by history, the government and people. Every working person in the US has been affected by my father’s work. Every person here is indebted to my father and it needs to be paid.”

Johnny read from his list of labor unions Larry started since 1929. It was part of the “thousands of documentation” Johnny was using as reference for the book he was writing on his father.

Already organized

San Jose State University Associate Professor Dr. Estella Habal explained, “Filipinos did not just start the grape strike. They were already organized since the 1930s. Larry Itliong was also part of the Stockton strikes in the 1930s. Filipino labor unions existed because Filipinos were not accepted in other unions.”

“People don’t know these. And often, a strike is broken when you pit one ethnic group against another. And the Filipinos were at the center of organized labor unions,” she added. “It was an arena filled with racism and social injustice. The Filipinos said, ‘Welga!’ and the Mexicans, ‘Huwelga!’ ”

Rita Medina, sister of the late Cesar Chavez who spoke for Chavez’s nephew Rudy Medina (who was busy at the Bay Area Rapid Transit negotiations at the time of this writing), told a packed auditorium about how the Filipino group sought out the Mexican group to gain numbers in their protest.

“Ma kept telling Cesar not to get into trouble. But Cesar said, ‘We’ll do it the non-violent way. We’ll join our Filipino brothers,’” Medina recalled.

Natural leader

Perhaps the only remaining union member from the Delano grape strike, Dolores Huerta, said, “I was responsible for getting Larry in the council. He started the organization in Stockton, which had the largest Filipino population outside of Manila back in the day, to include all ethnic farmers. That’s how the Agricultural Workers Association (AWA) came to be the Agricultural Workers Committee (AWoC).”

Huerta also shared her personal insights. “Larry was the natural leader of the group. Philip Vera Cruz was our great orator and Pete Velasco was humble. We were very close and are still in touch with each other’s families. We called each other brother and sister.”

The mural unveiling ceremony fortuitously occurred in the wake of Assembly Bill 123, introduced by California Assemblymember Rob Bonta (D-Oakland), the first Filipino-American elected to the California Legislature. Governor Jerry Brown recently signed AB 123 into law, which requires the state’s school districts to teach the contributions of Filipino-Americans to the farm labor union movement.

Pockets of intolerance

Bonta did for Filipino farm workers what California Senator Leland Yee did for Filipino World War II veterans. Despite this, pockets of intolerance still remain.

Former Santa Clara County Board of Education Trustee Darcie Green, now community and government relations manager for Kaiser Permanente, noted Arizona’s ban on ethnic studies, which Governor Jan Brewer signed into law in 2010, weeks after the signing of that state’s discriminatory anti-immigration bill. That law drew national attention and is now locked in court battles. But Arizona’s ethnic studies ban managed to slip through, largely unopposed.

Arizona’s ethnic studies ban was based on perceptions of anti-American bias in the teaching of some ethnic history. Union City Council member Pat Gacoscos recalled meeting a similar xenophobic backlash at the petition to change Alvarado Middle School’s name to Itliong-Veracruz Middle School.

“We got racist remarks and some of our buildings and businesses were tagged. The irony of it was most of the complaints reacting to the name change were from Hispanics. We were not prepared for the transition,” said Gacoscos.

Many see a mural as the writing on the wall; more dramaturgy than artistry. The uneven, patchwork-like quality bears witness to the hands of several contributors with differing styles. The same could be said of the Delano grape strike farm workers’ mural on the second floor of the Milpitas library’s Youth Center on Main Street.

Niki Escobar, Yunnie Snyder and Jessica Antonio worked without pay for two months on “the four foot by seven foot” mural, according to Antonio. “Niki worked on the background; Yunnie, on the foreground. I was detailing people. It took a lot of processing from sketch to digital painting to actual execution. There was more than one artist involved. The process is part of the purpose. We simultaneously learned and transmitted history. It was art and activism tied together.”

Speakers at the well-attended ceremony also included former San Jose Vice Mayor Cindy Chavez, Assemblymember Bob Wieckowski (D-Fremont), former Union City Mayor Manny Fernandez, writer and educator Oscar Penaranda (who said that “all of the gold in the 1848 California Gold Rush does not come up to one year’s field work by the Filipinos in California”), a representative for Congressman Mike Honda and Bonta’s mother, Cynthia Bonta.

Also in attendance were representatives from the Philippine Consulate General, San Jose State University students and alumni, various Filipino youth groups and activists, and community organization and labor leaders.