The clip features a voice, a Filipino’s, calm and full of conviction, explaining why he and others, including Mexicans, are marching.

The year is 1966. It is the height of the farm worker protests in California. In the background, you could hear the voices of farm workers chanting slogans.

“I am a machine,” the Filipino says. “We have to do this.”

By this, he means to strike, to fight back.

[You can listen to the audio clip here. https://leapinghorse.tumblr.

Theo Gonzalves came across the audio clip in his research work as an associate professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. He posted it on Tuesday, the start of Filipino American History Month.

It’s turned into a particularly special celebration this year.

On Wednesday, a bill aimed at highlighting the Filipino story in California became law. For Pinoys in California, the largest Filipino community outside the Philippines, it’s a big deal.

When people speak of farm worker struggles, they typically think of Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta and other Mexican leaders of the United Farm Workers.

That may soon change.

The new law now requires schools to teach students about the contributions of Filipino Americans to the California farm labor movement. The bill was pushed by Rob Bonta, the state’s first Filipino American assembly member.

“This is long overdue,” Theo says. “You know how people will sometimes complain about historical revisionism? The truth is that histories are always being revised and Filipino Americans aren’t going to wait for someone else to tell those stories.”

He wasn’t just speaking as an academic and historian. His brother was a member of the UFW.

“He could tell you that as a younger Filipino organizer and lawyer that the Latino elders in the organization, the ones who worked side-by-side with Filipinos from the Delano days, cherished the contributions of Filipinos to the movement,” he adds.

Delano is the California city where the great grape strike began. The Filipinos, led by Larry Itliong and Phillip Vera Cruz, started the strike, before the Mexican workers, led by Chavez, joined the protest.

It marked the turning point in the history of U.S. farm workers movement.

With the new law, he said “California’s children will learn more about Filipinos’ long tradition of hard work and active resistance.”

That long tradition was also what Alex Fabros, a military veteran who father was a civil rights activists and journalist, has been trying to highlight. He’s the force behind an exhibit called Filipino Voices, which had a successful run at the Steinbeck Center in Salinas.

“It’s a great thing this happened,” he told me. But there’s a challenge ahead, he added. “Do we have the money?”

In other words, getting the law passed is just one step, he said. There’s more work to be done. Even Bonta recognizes this.

“We plan to explore standard options for funding the provisions,” Amy Alley, Bonta’s legislative director, told me. “This may entail working through the legislative budget process.”

The good news is, 50 years after the height of farm worker struggles in the 1960s, the educators and advocates who will be teaching kids about the Filipino story have more resources to work with.

Many California colleges and universities already offer courses on Filipino American history. Carlos Bulosan’s classic, “America Is in the Heart,” is required reading in many of these courses.

Dawn Mabalon, a professor at San Francisco State University, teaches one of them. She made her own contribution to the body of work on the Filipino story this year with the publication of her book, “Little Manila Is in the Heart,” a history of the Filipino community in Stockton, Calif.

“Right now, only university and college students taking Asian American and Filipino-American Studies courses and specific history courses have the opportunity to learn about Filipino American labor organizing,” she told me.

“This law makes it possible for young people of all backgrounds, in classrooms in elementary, middle, and high schools, to learn about how people came together to protest injustice and demand humane working conditions and wages.”

“Overall, I think this is fantastic,” she adds. “This shows how visible and powerful we have become on a state-wide and national level as an ethnic group.”

Despite his own worries about funding, Fabros said, “We need to support Bonta to get the funds to make this happen.”

He’s currently working to bring the Filipino Voices exhibit to San Francisco.

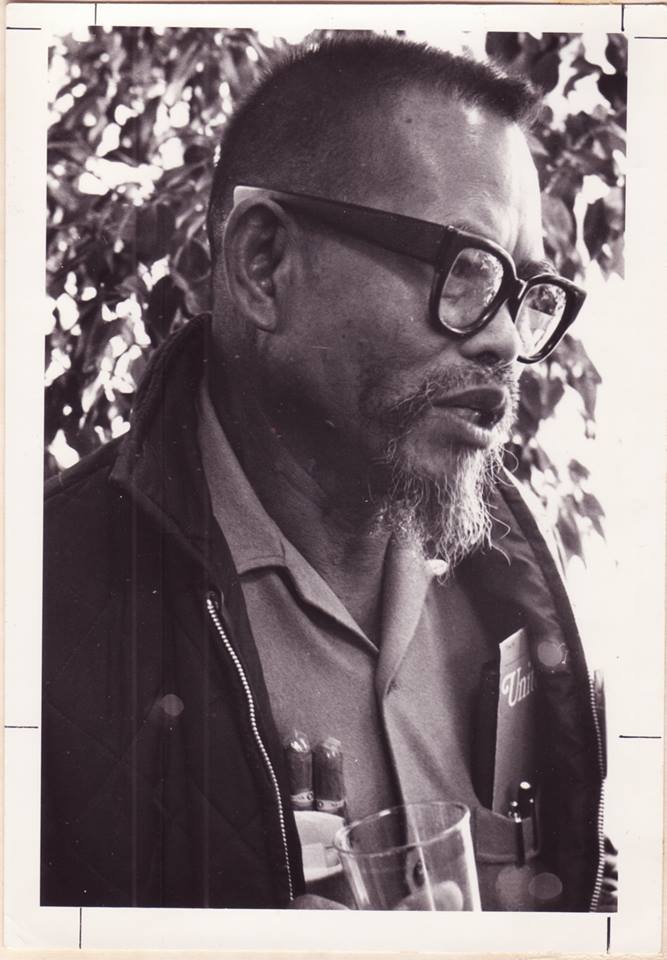

The exhibit features his late father who in his own passionate, even impatient, way spoke of the need to remember those who blazed the trail for California’s Filipinos.

“We had our families, our children,” a quote from his father reads. “We fought for them. Give them the citizenship. Now the newcomers always ask what we did. They don’t know. They don’t care. It’s too easy for them now. They are lucky. Sometimes they have problems. But they have their civil rights, not like when we first came here. We gave them the gift, the right to be a Filipino in America.”

Visit (and like) the Kuwento page on Facebook at www.facebook.com/boyingpimentel

On Twitter @boyingpimentel