OAKLAND, California–Domestic workers in California are optimistic that their annual income will increase and give them a more stable living condition with the passage last week of a landmark bill that would adjust wages, particularly overtime pay, in the entire state.

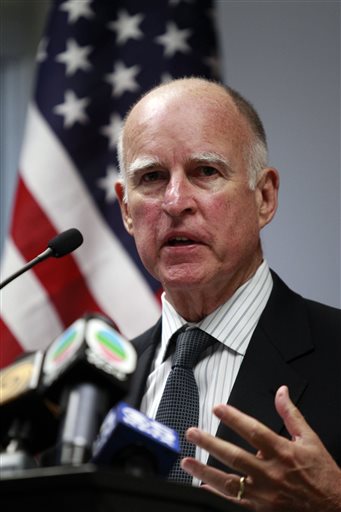

The bill is awaiting Gov. Jerry Brown’s signature by October 13. He vetoed the same bill last year.

Assembly Bill 241, also known as the California Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, introduced by Assembly Member Tom Ammiano (D-San Francisco), would guarantee overtime pay for domestic workers who work more than nine hours per day or 45 hours per week.

If it becomes law AB241 would affect an estimated 200,000 domestic workers in California.

Falling under the domestic work category are nannies, caregivers, house-helpers, and people working on a “one-on-one” care with patients who need special care or under a live-in arrangement.

Should Brown sign it, he would then set up a committee to review the success of the bill, and lawmakers would have three years to make it permanent.

A huge step

The recent approval by the state Assembly and the Senate mark a huge step forward for domestic rights in the state and would make California the second state in the nation, after New York, to pass such a bill.

Filipino Advocates for Justice Executive Director Lilllian Galedo, whose group is actively involved in pushing for the bill, said that caregivers fought hard for it.

Galedo said the bill covers all workers doing domestic work, including those in the care giving industry.

“Getting overtime pay is a critical demand of workers in this industry because most work more than eight hours a day,” Galedo said, “Many work 24 hours with no overtime pay. So, getting overtime pay will greatly improve their annual incomes and their chance at more stable lives.”

Galedo said there is no accurate count of the number of Filipino caregivers in California.

Summary of Domestic Workers Bill of Rights

IN BRIEF

AB 241, the Domestic Worker Bill of Rights would grant overtime protections to California’s personal attendants working in private homes. Personal attendants are caregivers and child care providers who spent a significant amount of time caring for children, elderly or people with disabilities.

THE ISSUE

Domestic workers are among the most isolated and vulnerable workers in the state. Historically, domestic workers who cared for property were given full wage and hour protections but those who cared for human beings were not. Personal attendants in California were excluded entirely from coverage under the Wage Order. Personal attendants were excluded from coverage on the erroneous belief that these workers were primarily young or elderly persons doing this work to supplement income received from their parents or social security benefits, respectively. In 2001, minimum wage protections were extended to personal attendants but they remained excluded from overtime. This bill extends overtime protection to personal attendants.

THE SOLUTION

AB 241 provides overtime protection to personal attendants as follows: one and one-half times the employee’s regular rate of pay for all hours worked over nine hours in any workday and for all hours worked more than 45 hours in the workweek. The bill is in effect for three years. The Governor will appoint a board of personal attendants and employers of personal attendants and/or their representatives to study the effect of this bill.

This bill does not cover among others personal attendants who provide domestic services through the In Home Support Service (IHSS) and Department of Developmental Services pursuant to the Lanterman Developmental Disability Services Act (DDS), close family members of the employer, babysitters who are under 18, casual babysitters.

BACKGROUND

In California, there are around 200,000 domestic workers who serve as housekeepers, nannies, and caregivers in private homes. Domestic workers are primarily immigrant women who work in private households in order to provide for their own families as

the primary income earner. Domestic workers are essential to California as they enable others to participate in the workforce.

Without these domestic workers many Californians would be forced to forgo their own jobs to address their household needs, the result being that the well-being of many California families and the economy as a whole would suffer. However, despite the importance of their work, some domestic workers continue to be excluded from overtime protections that other California workers enjoy.

The denial of overtime to personal attendants is rooted in the notion that their work is not valuable and legitimate work. In 1976, the Industrial Welfare Commission deemed caregiving “a source of rewarding activity,” conducted by individuals “merely for supplemental income.” The IWC relied on this rationale to exclude them from all coverage.

All other hourly Californian workers get overtime pay. Meanwhile, personal attendants who care for California’s children, elderly and people with disabilities do not. As the baby boomer population ages, more people will be turning to domestic work as their profession. AB 241 makes sure that personal attendants receive overtime for their hard work.

“It is not a permanent workforce because the level of exploitation is so high. Workers come and go,” she explained. “Filipinos doing care giving work are primarily an immigrant work force of documented and undocumented, primarily immigrant women, although the number of men is increasing, also immigrants. “

Dedicated organizers

FAJ has helped 80 to 100 caregivers directly, according to Galedo, the coalition supporting may have organized approximately 2,000 domestic workers in California.

“This campaign shows that the active organizing of a small number of dedicated organizers can win lasting change for a whole industry,” she added.

Fiona Cruz heads the Steering Committee for the California Domestic Workers Bill of Rights Coalition, a group made up of the Centro Laboral de Graton, Coalition for Human Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles, Filipino Advocates for Justice, Instituto de Education Popular del Sur de California, Mujeres Unidas y Activas, Pilipino Workers Center, and Women’s Collective of Dolores Street Community Services.

“A big number of Filipinos here in California are caregivers,” Cruz said, “Even though, a huge percentage of those who are caregivers work in care homes and already have rights to overtime, a lot of them either work part time, one-on-one or have experienced working as a caregiver one-on-one which are the ones who are affected by this bill.”

One in four domestic workers is paid below the state-required minimum wage of $8 an hour. In addition, many get no rest or meal breaks.

Domestic work is often a ticket to entry into the United States. Nearly three-quarters of domestic workers in California are immigrants, and 67 percent of them are Latina.

Domestic work has been regulated in California since 1976, supporters said, but home-based workers lacked the basic protections enjoyed by millions of other workers.

Cruz said domestic worker leaders themselves worked tirelessly to pass this bill.

“They have gone to Sacramento over half a dozen times to lobby this bill, in addition to all the local actions and events we’ve had.”

She said the group has also written letters and called legislators to push for the passage of this bill.

Excited

Meanwhile, Honor Nono, a caregiver-organizer of PAWIS (Pilipino Association of Workers and Immigrants) from Los Angeles, told INQUIRER.net her group is excited about this new development.

“A group of caregivers working in care homes–(those) doing one-on-one or 24-hour shifts will be the direct beneficiaries of this bill,” Nono said, “Although, it won’t have an impact on workers in care homes or facilities because they’re already covered by an existing law.”

“I pity those working under hectic conditions,” Nono lamented. “ It’s better if one is just working as companion of a patient, but those with dementia or alzheimer’s demand constant attention–caregivers don’t sleep at all, and this bill bill is a big move for them.”

Nono came to the United States in 2008 and worked odd jobs as nanny, cook and is now an administrator in a care home with 12 patients.

Nono stressed this is the only time domestic workers would be protected under the minimum wage law after 75 years, if Gov. Brown signs it.

“In the 1930s, house helps were commonly African Americans,” Nono recalled, “Now, most of those working on a one-on-one, live-in arrangement are Filipino professionals, some are nurses, teachers or doctors, who are transitioning immigrants.”

Salaries for live-in caregivers may range from $120 to $150 a day (24 hours), while Nono believed agencies get a cut of 50 percent, or a total of $250 to over $300 daily take.

“I for instance, will get a chance to get other part-time work or attend other family duties,” Nono said, “and caregivers will have the right to choose whether they can use the patients’ kitchen facilities because they commonly bring unhealthy foods to eat like noodles or left-overs just to get by. These are poor conditions and imagine how much weight each one lifts every day.”