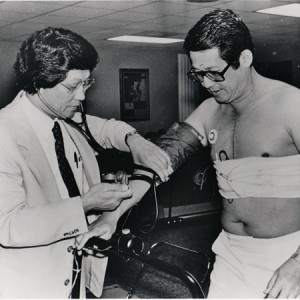

Ninoy Aquino with cardiologist Dr. Rolando Solis at Baylor Univ. Medical Center during his cardiac rehabilitation in June 1980. (Credit: Rolando Solis)

SAN FRANCISCO — I was 14 when I first saw Ninoy Aquino in action.

It was 1978. Ferdinand Marcos, hoping to legitimize his dictatorship in the eyes of the world, had called for elections for a new legislature.

Marcos was confident he would win easily even if he let Ninoy Aquino, then the country’s most well-known political prisoner, join the campaign.

That was a big mistake.

During a televised interview with journalists clearly aligned with the dictator, Aquino showed the country why Marcos feared him so much. It was a mesmerizing performance.

He out-talked the panelists sent to discredit him, responding to questions and allegations, eloquently and brilliantly, shifting comfortably from English to Pilipino and back.

Marcos shouldn’t have let him out of prison. Ninoy clearly was a dangerous adversary who exposed the regime’s most glaring flaws. The regime had to resort to the most brazen forms of electoral fraud to “win.”

But my views of Ninoy eventually evolved.

By the time I entered UP Diliman in the early 80s, I saw Ninoy as neither a superhero nor a saint.

Yes, he was an important figure in the fight against tyranny. But I had more questions about what he stood for, having been exposed to broader, more progressive ideas on the Diliman campus. Like many young people of on the UP Campus I grew more critical of Ninoy’s role in Philippine politics.

He was a leading opponent of the regime, but in the eyes of many from my generation, he also represented the old-style, elite politics that caused many of the country’s problems in the first place.

We didn’t use the word ‘trapo’ then, but we saw Ninoy as a traditional politician on which that pejorative term is based.

Not that young Filipinos of my generation rejected all traditional politicians. Not at all. We admired the likes of Lorenzo Tañada, Jovito Salonga and Pepe Diokno.

They may have come from the elite, but, during the dark years of dictatorship, they aligned themselves, in very concrete ways, with people like us – students. They even linked arms with factory workers and farmers.

Diokno, in particular, or Ka Pepe as we called him, became the epitome of the activist-politician that many of my generation revered.

He was a regular speaker at student demonstrations. He became respected as a fearless human rights crusader and a consistent critic of U.S. support for Marcos.

I still remember a human rights lawyer’s story of how Diokno would join fact-finding missions in remote barrios where he would be actively interviewing survivors or witnesses of abuses. The Diokno house in New Manila was open to activists and ordinary people who had joined the fight against dictatorship.

We admired Diokno. Ninoy, we respected, but also viewed with some suspicion as just another old-style politician angling for power.

Then came August 21, 1983.

I was at home watching TV with my family when my eldest sister walked into the room and said, “Patay na si Ninoy.”

The next day, on the U.P. Diliman campus, a professor observed the sadness and rage he saw in the eyes of ordinary Filipinos he met on jeepneys and on the streets. I was one of the hundreds of thousands who joined the rain-drenched funeral march for Ninoy on Aug. 31, 1983.

And the next three years turned out to be the most exhilarating and confusing, most exciting and frightening, most emotionally-draining and intellectually-stimulating period of my life and the lives of many Martial Law babies.

We all know how that story ended — a united people kicked out a bully. The nightmare was over.

Thirty years later, there may still be disagreements on Ninoy’s political record, and there are still many questions about his motives. I still do not see him as either a superhero or saint.

Many of the criticisms, in my view, are fair and deserve closer scrutiny. Others are so clearly over-the-top, cruel and sinister, many of them being spread by supporters of the dictatorship.

But one thing is clear: Ninoy’s death set us free from dictatorship. His story still matters.

There’s been speculation on why Ninoy came home when he did. But one point cannot be disputed: He came home at perhaps the worst time for someone considered as Marcos’s most feared enemy.

The Pinoy Hitler was at the height of his power. Many of his opponents were in jail or in exile. Ronald Reagan’s Washington loved him. Reagan even sent his Vice President George H.W. Bush to Manila to praise Marcos for his “adherence to democratic principles.” And Reagan himself later embraced the despot as a friend and ally during the Marcos state visit to the U.S.

Why in the world would you give up the safety of life in exile in Boston to take on a powerful despot backed by a world superpower?

A coward would have just stayed put and waited for a better opportunity.

Which is why despite any misgivings one may have about his politics, I join others in giving Ninoy credit for having had the courage to return to the battlefield.

The risks were clear, and yet he boarded that plane.

Visit (and like) the Kuwento page on Facebook at www.facebook.com/boyingpimentel

On Twitter @boyingpimentel