The last time I spoke with Joe Alfafara was at the funeral of the mother of his life partner, Anita. I had known Joe for more than 20 years but that lunch conversation, which turned out to be our last, was our most expansive in years. We talked about his life, and about his father, Isidro, and about his uncle, Celestino, both of whom immigrated to the US in 1929.

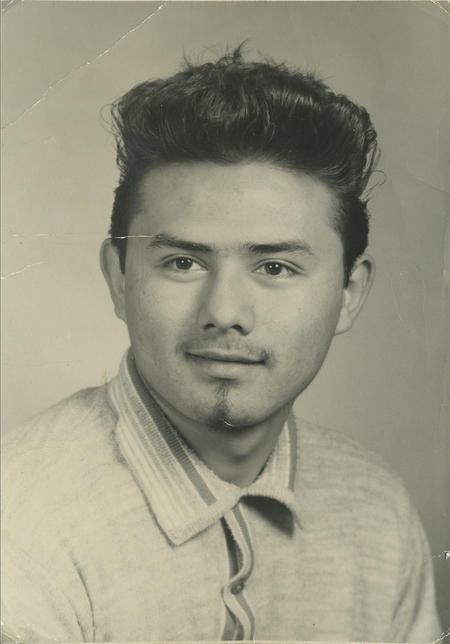

Joe died quite suddenly of a heart attack on June 23, one month shy of his 66th birthday, and we never did get to finish our discussion about his Uncle Cel whom he greatly admired. He was going to search for photos of his uncle who died in 1989 at the age of 90. I promised him I would one day write about his uncle’s historical achievement. So here it is, Joe.

Celestino Alfafara is celebrated in Filipino American history lore as the man who won “the California Supreme Court decision allowing aliens the right to own real property.” In the most recent conference of the Filipino American National Historical Society in Albuquerque, New Mexico in June 2012, “The Legacy of Celestino T. Alfafara” was the focus of the plenary on “Fighting Anti-Alien Property Laws”.

Before Alfafara, the only way Filipinos could own property in California was if they collectively purchased it in the name of their fraternal organizations like the Caballeros de Dimasalang the Gran Oriente Filipino and the Legionarios del Trabajadores.

When I read the text of the Alfafara California Supreme Court decision that was decided on May 22, 1945, I was surprised to learn that it was not based on a violation of the “equal protection” clause of the US Constitution. In fact, the California Supreme Court specifically ruled that its decision did not violate the Alien Land Act, a state initiative passed by California voters in 1920 barring aliens from acquiring real property in the state.

Celestino and Isidro Alfafara arrived in the US in 1929 when they were already about 30, unlike most of the 125,000 younger Filipinos who immigrated to the US from 1908 to 1925. It was their misfortune to enter the US job market just as the Great Depression was driving poor whites from Oklahoma and other Midwest states to compete with Filipinos and Mexicans for the lowest paying farm worker jobs available in California.

Too old to enlist in the US military, Celestino and Isidro endured years of working in intermittent seasonal labor in the fields of Hawaii and California, as cannery workers in Washington and Alaska and as bus boys, janitors, cooks, and other hard jobs. What sustained them was their dream to one day own their own piece of land.

That opportunity came to Celestino in June of 1944 when he found a piece of property in San Mateo County that was on the market for $65. He made a written offer to the seller, Bernice Fross, who signed the purchase agreement. But after Celestino handed her the money, Fross changed her mind and refused to transfer the property to Celestino. So he sued for specific performance of the contract.

At the court trial of the contract dispute, Fross argued that it was unlawful for her to sell her land to an alien. The judge concluded, however, that Celestino “is not an alien and is not barred or prohibited from holding or receiving real property in the State of California by the Alien Property Initiative Act of 1920.”

Fross appealed the lower court decision all the way to the California Supreme Court. On May 22, 1945, Associate Justice John Wesley Shenk penned the unanimous decision of the court.

Under the California Constitution of 1849, Shenk wrote, the right of to acquire property was an “inalienable” right, a right that was also to be enjoyed by “foreigners who are, or who may hereafter become, bona fide residents of this state.” A 1913 law extended this right to include “aliens eligible to citizenship.”

In 1920, through the state initiative process, the Alien Land Act was adopted which barred the taking and holding of real property by aliens ineligible to citizenship.

As Justice Shenk explained, “under the laws of this state and of the United States, the plaintiff is entitled to acquire and possess real property unless he is an alien, and is ineligible to citizenship. The two factors must concur. In other words, he must not only be an alien but he must also be ineligible to citizenship (to) be excluded from the right to acquire and hold property in this state.”

But, he also wrote, “it is likewise clear that the plaintiff is not an alien” because an “alien” is judicially defined to be a person who owes allegiance to a foreign government.

Since Celestino was not an “alien”, he could purchase property in California. Bernice Floss was ordered by the Supreme Court to sell her property to him. And that’s how history was made.

(Rodel Rodis taught Philippine History and the History of Pilipinos in America at San Francisco State University and at Laney College. He is now an attorney in private practice and can be reached by email at Rodel50@gmail.com or by regular mail at the Law Offices of Rodel Rodis at 2429 Ocean Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94127 or call 415334.7800).