QUEZON CITY—Last week, I was fortunate enough to attend the Philippine premiere screening at the UP Film Center in Diliman of the restored print of the late great filmmaker Lino Brocka’s Maynila: Sa Mga Kuko ng Liwanag. The title has been translated as Manila in the Claws of Light, but I prefer to translate “Liwanag” as “Neon,” as in my view the latter much more accurately symbolizes the temptations of a modern city that both attract and doom all those seeking a way out of cul-de-sac lives, as happens to the two ill-starred lovers in the film who are promdis—from the province. As was Lino, and not from landed gentry either, but from the proletariat, which explains why he had the right instincts and smarts in handling his material, drawn invariably from contemporary urban realities.

The restored print had its world premiere at Cannes last May, as part of the Classics section. According to Sineng Pambansa (National Cinema), the newsletter of the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP), three new Philippine films were also screened at Cannes: Adolfo Alix’s Death March, Lav Diaz’s Norte Hangganan ng Kasaysayan, and Erik Matti’s On the Job—a total of four Philippine films, the most ever shown at one of the world’s oldest, and most prestigious, film fests.

The restoration of the Brocka classic was a collaborative project of the FDCP, Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation (WCF), and L’immagine Ritrovata, the well-known restoration laboratory based in Bologna, Italy. Both Briccio Santos, chair of FDCP, and Benedict Olgado, director of the National Film Archives of the Philippines, are to be commended in their labors to bring back to the screen deserving Filipino films that have for one reason or another been out of circulation. Already their efforts have resulted in the restoration of Manuel Conde’s Genghis Khan, though not the full-length two-hour film but the 90-minute version.

Maynila remains as powerful and relevant today as it was when it first was screened, in 1975, when martial law had been in place for three years. A beautiful village lass, Ligaya Paraiso (played by a luminous Hilda Koronel) is lured to Manila by the prospects of a goodpaying job by an unscrupulous and predatory recruiter. Ligaya winds up in a prostitution ring, but a Chinese businessman takes a fancy to her and keeps her imprisoned at his Binondo home. In the meantime, her hometown beau, Julio, a fisherman (played by Bembol Roco, in his debut screen role) comes to Manila in search of Ligaya. In order to keep body and soul together Julio takes on odd jobs, including as an underpaid construction worker and, briefly, as a sex worker. In his odyssey through the underbelly of the city we see the slums—and these are real slums, not some back lot or sound stage—in all their squalor and poverty. In the faded colors, the decrepit facades of homes and businesses in Binondo, in the world weariness the faces around Julio exhibit (in contrast to his soulful looks and youth), we sense the moral rot and despair that infest a city that no longer appears noble and seems royal only to those who exploit the masa. Of course, it ends tragically: that famous freeze-frame of Julio with a desperate, haunted look, a man who knows he is about to die.

I don’t know if Imelda Marcos ever saw the film, but it certainly would have infuriated her. A woman who ordered walls built so as to screen squatter settlements from Pope John Paul’s view when he first visited in 1981, would not have been a fan of Brocka’s films, nor of other filmmakers more interested in the sound of poverty and misery than in rose-tinted representations of reality. She was said to be equally dismayed by the late Ishmael Bernal’s 1981 noirist Manila By Night. For the film to be screened abroad, the title had to be changed to City By Night.

Brocka’s neo-realist sensibility directly opposed her own sense of what film should be. She espoused a philosophy, if it can be called that, that art, particularly cinema, should show the good, the true, and the beautiful, and that Philippine films should make its viewers want to be Filipinos. Not surprising that The Sound of Music was said to be one of her favorite films. Ironically, Brocka’s first film, Wanted Perfect Mother, was partly based on the Julie Andrews vehicle.

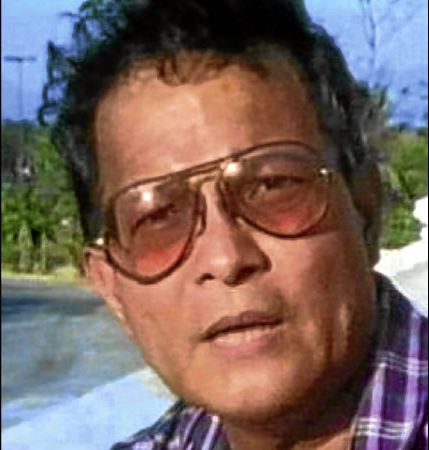

Brocka was a fearless and much-needed voice not just in cinema but also in the larger society, at a time when martial law meant a curtailment of civil liberties, including of course the fundamental right of self-expression. He co-founded Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP) in 1983, since he felt that, artists being citizens as well, they too had a responsibility to speak out against social injustices as well as to represent cultural workers in their struggle to freely express themselves.

In such films as Insiang, Jaguar, and Bona, he continued to portray the lives of the hoi polloi struggling to find meaning and dignity in a society that seemed to systematically deny ordinary folk the opportunity to better themselves. Even in the post-Marcos decade, he continued to act as a gadfly. In his Ora Pro Nobis, in my view, one of his strongest films (as is Insiang), the underlying message was that while the Marcos regime had been deservedly swept from office, the new order wasn’t necessarily that much of an improvement, especially when it came to human rights. In part, it reflected his disillusionment as a member of the 1986 constitutional commission charged by President Corazon Aquino in drafting a new national charter, to replace the one put into place by Marcos. He resigned before the final version was drawn up. In 1991, his life was cut short in a road accident, and in 1997 was posthumously named National Artist for Film.

Keep an eye out for Maynila, as it will have a commercial run beginning August 7 particularly if you’ve had it with the usual mind-deadening, special-effects-laden blockbusters.

Copyright L. H. Francia