SAN FRANCISCO – This Father’s Day, I’m honoring my grandfather. I never met him. He died two years before I was born.

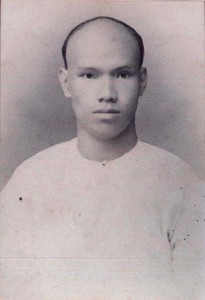

All I have are my own father’s stories of his dad and some pictures. There’s one of my lolo with the traditional Chinese pigtail. Then there’s a 1927 family photo in Naga City. Yes, it’s a big family – he and my Lola Aquilina had 16 children.

I have only sketchy details of the life story of Sy Sing Douy, aka Luis Pimentel, mostly from my father who spoke highly of his parents.

“No read, no write, but they worked hard,” my father would say.

Sy Sing Douy came from a poor family in Xiamen, Fujian province in southern China. Poverty forced him to leave and take a chance in another country down south. He was a teenager when he came to the Philippines at the turn of the 20th Century. He was penniless and the future looked bleak.

But he and my grandmother were astute business people. Sy Sing Douy became Luis Pimentel after he converted to Catholicism and adopted the name of his godfather. In Naga City, the couple thrived, building a rice milling business from scratch, acquiring property.

My grandfather was a serious, no-nonsense type of guy, according to my father. You can tell from the family photo. He’s not smiling.

I’m actually kind of glad I never got to know him. For my father also said he was big on discipline which he imposed with a yantok, a rattan stick.

But I also wish I had known my lolo from China. I wonder what Sy Sing Douy, aka Luis Pimentel, would say about the way things have turned out for the Philippines and China – for his adopted country and for his homeland.

What would he say about the fight over islands scattered between the two countries…about tensions following the death of a Taiwanese fisherman during a confrontation with the Philippine Coast Guard and the harassment of Filipinos in Taipei … about the taunting of the Philippine football team and their fans in Hong Kong?

I had always known about my Chinese heritage, though my father never really pushed me to explore that identity. In fact, he never referred to himself as Chinese or Chinoy. Not that he denied or rejected his Chinoyness. In fact, like me, he was curious about it. We even talked once about taking a trip to Fujian to look for relatives, but the plan never pushed through.

But Chinoy was just not an identity we felt compelled to embrace. As far as I know, my father always thought of himself as Filipino. That’s also how I’ve always seen myself.

In fact, I will confess this: Growing up, I even embraced some of the anti-Chinese prejudices of many Filipinos. I made fun of people with Chinese accents, and laughed at jokes about the Chinese.

I regret that now, of course.

In a way, I also regret not having been exposed more to my Chinoyness. That could perhaps help me understand better the tensions between the Philippines and its neighbors.

It’s a troubling time.

It’s a time for sobriety and passion, for calmness and a sense of urgency, for patience in dealing with complex geo-political disputes, and for decisive, even impatient, responses to those who would seek to inflame the conflicts with narrow-minded xenophobia.

It’s a time to listen carefully to the rhetoric – and to go beyond it.

And it’s a time when we must be quick to take note, highlight and celebrate every effort to denounce racism and xenophobia of all forms and from all sides.

Take the South China Morning Post’s editorial about the attacks on the Filipino football team and their fans. It was powerful and clear: “Racial abuse is nothing to be proud of, not amusing, nor clever; it is shameful.”

It is so easy to forget that, despite their differences, Filipinos and Chinese share so much in common. Ironically, I learned to appreciate that here in America where Filipinos and Chinese have battled side by side for decades for equality and against prejudice.

I was reminded of this again recently when my family and I visited Angel Island on San Francisco Bay. It was there that thousands of immigrants from Asia, including many Chinese and Filipinos, were processed when they arrived. Because of anti-Chinese U.S. immigration laws, many Chinese were detained on the island and later even deported.

Poem written by Chinese detainee at the Angel Island detention center near San Francisco. PHOTO/BENJAMIN PIMENTEL

As far as I know, my grandfather never wrote of his experiences as an immigrant, including his reasons for fleeing to the Philippines from China. But I suspect he shared the same hopes and fears as a Chinese detainee on Angel Island. His name was Lin. Like other Chinese detainees, he expressed his hopelessness in poetry carved on the walls of the prison barracks.

“The Americans did not allow me to land,” read a translation of his poem.

“I was ordered deported

“When the news was told

“I was frightened and troubled about returning

“To my country

“We Chinese of a weak nation

“Can only sigh at the lack of freedom … ”

That was written many decades ago. So much has changed.

Today, China is strong. The Philippines is still struggling, though in some ways, also getting stronger.

But in this scramble for strength, in this push for prosperity, and in light of the shared histories of the peoples of the Southeast Asia, the South China Morning Post editorial should be repeated over and over again throughout the region: “Racial abuse is nothing to be proud of, not amusing, nor clever; it is shameful.”

Visit (and like) the Kuwento page on Facebook at www.facebook.com/boyingpimentel

On Twitter @boyingpimentel