In fact, advance word of the film’s power had the line of people waiting to see it snaking around the block in front of the Kabuki Theater during its Sunday, March 17 screening.

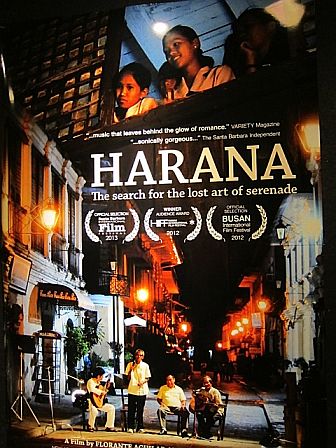

The early evening chill failed to dampen the enthusiasm of the sell-out crowd for the San Francisco premiere of one of the Filipino entries to CAAMFEST. It had already won for its director, Benito Bautista, a Philippine Daily Inquirer Indie Bravo award last December in Manila. “Harana” also received positive responses at international film festivals in Dubai, Los Angeles, and Pusan, South Korea.

Narrated by Florante Aguilar, the movie traces his journey of rediscovering his homeland’s music after attending the funeral of his father in 1999 in the Philippines, after an absence of 12 years.

An epiphany

A classically trained guitarist who studied at the University of the Philippines and Manhattan School of Music, Aguilar had an epiphany upon his return to San Francisco.

“I found myself playing only Filipino tunes,” he says. This led him to explore harana (serenade), an old tradition of courtship widely practiced in rural areas in the Philippines before the advent of karaoke and videoke. A man, accompanied by a guitarist and a few friends, would serenade a woman beneath her window with romantic ballads.

A musical tour

The film takes viewers on a musical tour of the old days in the Philippines. Through the stories and songs of three masters of harana, who are in their late years. Aguilar did not have to look far to find master practitioners of the musical form. In his home province of Cavite, he discovered Celestino Aniel, a 66-year-old farmer, and Romeo Bergunio, also 66, a fisherman. He then traveled up north of Manila and found Felipe Alonzo, 78, in Vigan, Ilocos Sur.

Together with Aguilar, the men became known as the Harana Kings and recorded a CD and performed in Manila and Los Angeles to much acclaim. Again teaming up for the film, the Harana Kings sing beloved love songs like “Dungawin mo Hirang” and “O Ilaw,” which resonated with many audience members at the Kabuki.

Vangie Buell, author and former president and member emeritus of the Filipino American National Historical Society, says she cried upon hearing “O, Ilaw.” “It reminded me of Filipino farm workers in the 1950s who would serenade us at parties in Stockton,” Buell recalls.

Salve to homesickness

She adds, “Music was a salve to their homesickness. After a week of back-breaking work in the fields, these men, many of whom did not have families of their own, would get together, bring out their guitars and play and sing beautiful Filipino songs.”

Michael Magnaye, a documentary filmmaker who studied filmmaking at Stanford University is effusive with his accolades for the movie: “The power of this film is its ability to bring together an audience from many generations, who came together for entertainment, inspiration, and nostalgia.”

He also notes, “A manong seated to my left was singing along throughout the movie. At first, I resented the distraction, but later I became envious that he knew many of the lyrics. I would have done the same thing had I known the words.”

But it was not only the music that captivated the audience. The beautiful shots by cinematographer Peggy Peralta made the Filipino viewers nostalgic for their homeland.

Spectacular cinematography

Peralta explains that she worked closely with Bautista to create the mood for the film, capturing Filipinos and the country at their romantic best in a number of scenes: the haranistas with weather-beaten faces, singing to a small enraptured audience of women and girls; a young man from Tondo, one of the poorest districts in Manila, shyly requesting Aguilar to play the nationalistic song “Ang Bayan Ko”; a Harana performance in the middle of the main street in historic Vigan under a full moon; and spectacular sunsets framing the songs.

Filmmakers, speaking after film-showing: (From left) Benito Bautista, director; Emma Francisco, assistant director; Florante Aguilar, concept writer and executive producer; Fides Enriquez, executive producer.

“Filming Harana made me fall in love with the Philippines all over again,” says Peralta.

Like Peralta, many in the audience ended up with a better appreciation of their country of origin after watching the documentary, which was described by the San Francisco Chronicle as “one of the best films of the festival.” Some were left in tears; others wanted to learn more about the dying art of harana; and the rest were humming familiar ballads from the movie.

The reaction seems to affirm what Aguilar and Bautista had set out to do when they first conceptualized the project.

“The film is a symbol of a vanishing tradition,” Bautista states. “If we don’t record it, everything will be overcome by modernity, ambient noise and the Internet.”

Juxtaposing modern technology with old traditions was something Bautista already had in mind in designing the film–from the opening interview with an older woman undistracted by the incessant ringing of her cell phone to the final poignant scene showing the ailing Aniel, singing a romantic ballad to a videoke at a deserted store. (Aniel died before the movie was premiered in 2012 at the Cinemalaya Independent Film Festival in Manila, where it received a standing ovation.)

Proud of roots again

That “Harana” struck a strong chord among Filipino audiences on both sides of the Pacific was not lost on Buell, who saw the film at the Pacific Archives in Berkeley. She said that she was happy to see a crowded theater with a lot of young people, many of whom were not familiar with the art of harana. “It is important for them to know that they come from a long musical tradition to make them proud about their identity,” Buell remarks.

Bautista, who came to the U.S. in 1984, is of similar mind. “I would like the global Filipino to be aware that they have a proud heritage beyond iconic personalities like Manny Pacquiao. While we filmmakers can contribute through projects such as ‘Harana,’ everyone has a role to play be it in the field of music and art, writing, or new technology.”

From the positive reviews of critics and international audiences, it seems that Aguilar, Bautista and the rest of the “Harana” crew have succeeded in imparting this message.

[Note: On March 24, 2013, in the course of writing this article, Felipe Alonzo, one of the three master haranistas, passed away, leaving Romeo Bergunio as the only surviving member of the group.]