This story is about journalism.

It’s also about my father which is, in a way, odd because my father didn’t really think much of journalism as a profession — especially for his own son.

He wanted me to be a doctor or a lawyer. So it came as a bit of a surprise for me to find out that he once was deeply involved in a serious journalism project.

Although dabbling in the field in which I now make my living nearly cost him his life. Actually, his brief journalism stint was not about making a living or exploring a career option.

It was about fighting back.

The story began 70 years ago in 1943 during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. A group of nine young men in Naga City, including my father, Benjamin Pimentel Sr., eager to do their part in fighting for their country’s freedom, decided to start an underground newspaper.

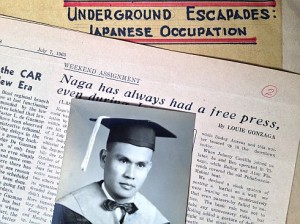

Their exploits were recalled in a series of articles in the Naga Times published in 1963 written by one of their members, Louie Gonzaga. The lead article’s headline boasts, “Naga has always had a free press.”

“Naga is, indeed, the cradle of Bicolandia’s free press,” Gonzaga wrote. “Even during its most trying times, we have always had some printed medium for the free discussion of public issues.”

The paper, which were actually just single page leaflets, was simply called “V,” for ‘victory.’

“What served as its name plate was an attractive red seal, consisting of an equilateral triangle wedged on a ‘V’ and encircled by the slogan, ‘FROM A MOUNTAINSIDE, WE LET FREEDOM RING.’”

The line was based on an American patriotic song. But it was only partly an affirmation of their alliance with the Americans. The slogan was also meant to “mislead the Japanese” by making them believe “that the leaflets were printed in the hills by the guerrillas.”

In fact, the paper was being printed in Naga City with the help of a manual typewriter and a mimeographing machine. My father played a key role in the production side of the underground publication.

“Ben Pimentel carved the rubber seal and his dexterous hands fashioned a primitive but efficient mimeographing machine,” Gonzaga writes.

The secret cell embraced “tight security measures.” One was an agreement “not to take into confidence any brother or close relative of any of the original members of the paper’s staff.”

“We did not like any member to be burdened with such brotherly affection as to compel him to reveal our secrets to save a brother who might have fallen into the hands of the enemy,” Gonzaga wrote.

It proved to be a tough rule to impose. The younger brother of a member accidentally barged into one of their printing sessions and was eventually accepted as a cartoonist.

Then a friend of one of the original conspirators also found out about the secret movement. “He used a peculiar type of blackmail in forcing himself into the group by threatening it with exposure if he was not taken in,” Gonzaga wrote.

On July 3, 1943, the first issue of the guerrilla newspaper hit the streets of Naga. For its opening salvo, the paper blasted the upcoming inauguration in October of the Japanese-sponsored puppet Philippine government with an editorial and editorial cartoon.

The guerrilla journalists quickly found themselves in hot water. The reaction from the Japanese authorities was swift as the Kempetai quickly launched an aggressive hunt for the culprits.

It was at this point that journalism turned out to be a dangerous trade for my father.

Questioned by the Kempetai, the Japanese secret police, a fellow Nagueno, Fred Vergara, inadvertently divulged during interrogation that only my father, other than Vergara’s father, had exceptional skills for making a really good rubber stamp.

Fortunately, after he was released, Vergara managed to warn my father that he could be a target because of what he said. When he was picked up by the Kempetai, my father was ready with answers. He survived the grilling by convincing the Japanese authorities was many young men who went to trade schools knew how to make rubber stamps.

Distributing the leaflets became the toughest hurdle. With the Japanese authorities already on alert, the underground journalists had to be creative.

“We devised a sleek system of posting a leaflet on a wall we were leaning on so unobtrusively that even passers-by failed to notice,” he continued. “The basic rule was not to take any unnecessary risks.”

They posted them in public places, slipped them under doors, windows and places “where they would surely be found in the morning and read,” Gonzaga wrote.

Despite the rule against unnecessary risk-taking, one member dared to post one on the front door of the Kempetai office. At times, they threw leaflets into a crowd.

During the Penafrancia festival of 1943, they distributed leaflets in Naga market stalls the night before the festivities, sometimes throwing folded leaflets onto the mosquito nets of the sleeping stall occupants.

In the Santacruzan season of 1944, my father teamed up with another member in leaving leaflets in the local theater and throwing them at calesas passing in the street.

On New Year’s Eve of 1944, they collected empty packs of Japanese cigarettes, stuffed them with leaflets, put the packs in a boxes which were then gift-wrapped.

They then approached small boys and, pretending to speak Tagalog with Japanese accents, instructed them to deliver the ‘gifts’ to several dances being held in town that night. It was dark and the boys could not tell that the gift-givers were actually Filipinos.

“There were scrambles for what was thought were presents of Japanese smoke,” Gonzaga wrote. “It must have been the only time when such dances became impromptu reading sessions.”

(Of course, I wondered why they would put the small boys at risk in such a scheme.)

Eventually, the guerrilla newspaper was shut down after members of the secret group took “separate guerrilla ways.” The guerrilla journalists turned into armed guerrillas joining different units in the resistance movement. Gonzaga wrote that my father “became an intelligence operative” of one guerrilla unit and “was sent to Sorsogon on a mission.”

Yes that sounded like an exciting adventure although my father himself painted his own guerrilla career in far less glamorous terms. He was assigned to “intelligence,” he told me, because he was such a poor shooter. “I could only hit coconuts,” he once joked.

It was Gonzaga who kept their mimeograph machine, their secret seal and other publishing paraphernalia in his house. But “when our house burned during the senseless fire bombing of Naga by American planes in March 1945, we completely lost what should have been our most cherished souvenirs of the war.”

In the Naga Times editions in which he recalled the story of the guerrilla publication, Gonzaga even offered twenty pesos “for every genuine copy” of the secret paper, “a mimeographed leaflet identified by a red seal with the slogan ‘FROM A MOUNTAINSIDE, WE LET FREEDOM RING.’”

I don’t know if Gonzaga was successful fifty years ago in trying to recover copies of the guerrilla paper.

In any case, my father kept copies of the Naga Times account of his ‘guerrilla journalism’ career, which were published the year before I was born.

“He kept the articles in a filing cabinet full of manila envelopes most of which contained family and business records, including our school report cards and even clippings of my articles.

The Naga Times articles were clearly special. He kept them in an envelope with a carefully printed label in my father’s distinctly neat, elegant writing style.

It read: “Underground Escapades: Japanese Occupation”

On Twitter @BoyingPimentel Visit (and like) the Kuwento page on Facebook at www.facebook.com/boyingpimentel