Changes in Asia set to shape US policy

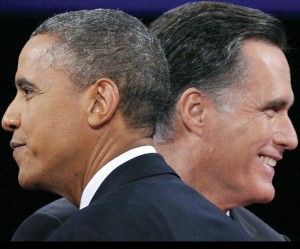

US President Barack Obama and Republican challenger Mitt Romney walk away after greeting each other at the end of their third and final debate at Lynn University in Boca Raton, Florida, on Monday. AFP FILE PHOTO

WASHINGTON—Changes could be in store for US-Asian relations, but that has little to do with presidential race. Lost in the backbiting between President Barack Obama and Republican Mitt Romney over China is that they generally agree on their approaches to Asia. But whoever wins the November 6 vote will have to deal with a region in flux — and figure out how to keep simmering tensions from boiling over.

Leadership changes are imminent in East Asia’s dominant economies — China, Japan and South Korea — in the midst of territorial disputes that could spark conflict. The new leaders who emerge will be crucial in setting the tone for relations with the next occupant of the White House.

Just two days after the US election, China begins its once-in-a-decade Communist Party Congress that will usher in a new crop of party leaders. Japan within months is expected to hold elections, as the popularity of the country’s seventh prime minister in seven years sinks. And in December, South Korea holds presidential elections that are likely to set it on a more conciliatory track in its relations with North Korea.

How the US gets on with China affects the entire region. Many Asian countries look to China as their main trading partner, but they regard the longstanding US security presence as a defense against China’s rapid military buildup.

Xi Jinping, who will take the party helm and be anointed China’s president in March, is a largely unknown quantity. Some suggest his elite background, military ties and confident air might portend a more assertive hand in foreign policy than the incumbent, Hu Jintao.

Bonnie Glaser, a China expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank, said she expects Xi to continue constructive ties with the US. While Washington will push Beijing to adhere to international law and norms, she doesn’t expect a new administration to pick a fight with the new Chinese leadership, which itself will be focused on pepping up economic growth and maintaining domestic stability.

“The United States may be to some extent reactive,” Glaser said. “If China is seen as more assertive, challenging US interests anywhere, it will get a tougher US policy.”

Despite Romney accusing Obama of being soft on Beijing’s trade violations, and Obama attacking Romney’s former business interests for outsourcing jobs, the candidates agree that the United States needs to engage Beijing and make the US presence felt more in the Asia-Pacific, an area of growing economic importance.

Obama has deepened ties with China, but there are new areas of tension.

Beijing is accusing Washington of shutting out major Chinese firms, particularly its technology giants that are seeking a foothold in America. US diplomatic interest in maritime territorial disputes between China and its neighbors in the South China Sea also annoys Beijing.

Washington is keeping a lower profile in a potentially more explosive territorial spat that has flared between China and staunch US ally Japan. US treaty obligations, however, require it to help Japan if disputed islands in the East China Sea come under attack.

China has sent ships to the area in a show of force, and Japan shows no sign of making diplomatic concessions. If Japanese opposition leader Shinzo Abe gains power in elections that unpopular Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda is expected to call soon, tamping down tensions will become even tougher. Abe, a former prime minister with nationalist tendencies, is considered a hawk on China.

The next US administration will also be grappling with South Korea’s leadership change and how that affects cooperation on North Korea, a perennial regional flashpoint.

Obama has hewed to the tough stance of President Lee Myung-bak, but the next South Korean leader is expected to pursue a more conciliatory approach to the North, which could make it tougher to coordinate policy.

There is little appetite in Washington to try for a new agreement aimed at the North dismantling its nuclear weapons program in exchange for aid. A February pact to give food in return for nuclear concessions collapsed when the North fired a long-range rocket. Pyongyang has been hinting it could discard 2005 commitments on denuclearization and declare itself a nuclear state, which would be unacceptable to Washington.

Judging from comments by policy advisers, Obama remains open to US-North Korean talks but first seeks concrete steps from Pyongyang on halting missile and nuclear tests and freezing uranium enrichment. A Romney administration would be likely to seek tighter sanctions, which might put it at odds with a more moderate South Korean policy, although a sudden disagreement with Seoul on nuclear issues is unlikely.

North Korea, which counts China as its only major ally, has scarcely registered as an issue in the election campaign. The only Asia-related policy promise that has garnered attention has been Romney’s vow to designate China as a currency manipulator, a step that could strain US-China ties.

History shows that the China relationship is prone to dramatic ups and downs.

Within three months of taking office in 2001, George W. Bush was thrust into a China crisis after a collision between a US spy plane and a Chinese fighter jet. Under Bush’s predecessor, Bill Clinton, US-China relations started badly, then improved, only to deteriorate sharply after the mistaken US aerial bombing of Beijing’s embassy in Belgrade in 1999, which sparked vociferous anti-US protests.