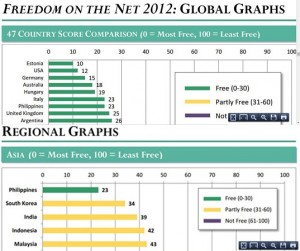

SAN FRANCISCO—Here’s something to think about: Filipinos enjoy the greatest amount of freedom on the Internet in Asia, according to a new report.

In fact, Internet use in the Philippines is the sixth freest in the world, according to the study by The Freedom House, a Washington DC based advocacy organization.

The report, which you can check out here, shows the Philippines with the green bar designating a “free” country, along with such countries as Germany, Italy, the U.S., and Estonia.

In Asia, the Philippines is No. 1 and the country with the only green bar. A distant second is South Korea, with a “yellow bar,” for ‘partly free,’ followed by India, also with a yellow bar.

However, the news comes at an odd time for Filipinos.

There’s a new Philippine law that many fear will end up curtailing the rights of Filipino netizens, or at least convince many of them not to be too critical of people or groups in positions of power.

The opposition to the online libel provision in the new cybercrime law — which could potentially make even clicking on a “like” button a criminal offense — is mounting, and that’s a good sign.

Sen. Tito Sotto, who has admitted pushing for the provision, still doesn’t get what the fuss is about, telling CBS.com that he pushed for the law because “I believe in it and I don’t think there’s any additional harm.”

But as lawyer Ted Te told me, the provision “is so pernicious and so malicious and so utterly stupid.”

“It is really a threat to freedom of expression because the Sotto rider fails to take into account the nature of online writing and the ease by which an item can be reproduced, forwarded, disseminated and passed on which, in turn, produces questions of source and attribution,” he continued.

By now, many Filipinos know how this fiasco involving Sotto unfolded.

Perhaps the most outrageous part of the controversy is the way Sotto has tried to make it appear as if the social media bloggers spread lies about him.

They did not. What they published – the lifted passages from blogs and the speech of Robert F. Kennedy — were true, and even Sotto and his office acknowledged this.

Still, when asked about the protests against the new law, Sotto told the Philippine Daily Inquirer, “I can’t see the logic.”

“If mainstream media are prevented by law from cursing and engaging in character assassination, why should those in the social media and in the Internet be exempted from such accountability,” he added.

Sotto also told the Inquirer: “What’s so special about (mainstream journalists) that they have those prohibitions, and that they (social media bloggers) don’t?”

This is what he clearly does not understand: In this controversy, Filipino social media bloggers proved to be “special.” That’s because, thanks to them, a high-profile political figure’s shenanigans were exposed.

That’s one thing that should really be highlighted in this dispute: Filipino bloggers, not the Philippine media, broke the story about Sotto using other people’s writing without proper attribution.

They got the story first, before Philippine media picked it up. In fact, social media in the Philippines and other countries has helped mainstream media do a better job reporting and explaining what’s going on.

It would have been an entirely different matter if some blogger had wrongfully accused Sotto of plagiarism, and those untruths were spread by the media.

But that’s not what happened.

Are there lies and falsehoods on the Web? Yes. That’s not news, and many news organizations are learning how to navigate that new frontier by ignoring or exposing those falsehoods.

And in this particular case, in which a politician was caught with his pants down not just once but several times, Filipino netizens clearly played a positive and constructive role.

This point is important based on the Freedom House’s analysis of countries “where the Internet remains a relatively unobstructed domain of free expression when compared to a more repressive or dangerous environment for traditional media.”

The report featured a graph showing countries where there is a sizeable gap, based on the group’s analysis, between press freedom and Internet freedom. The Philippines was one of them, which, of course, is also not surprising given the threats and over-the-top libel laws that Filipino journalists still face.

Still, for the Philippines, the Internet has, at least, remained unfettered and effective in checking and exposing the abuse of political power.

But that could easily change.

The report found that “restrictions on internet freedom in many countries have continued to grow, though the methods of control are slowly evolving and becoming less visible.”

One part of the report is worth quoting in full:

“Responding to the rise of user-generated content, governments around the world are introducing new laws that regulate online speech and prescribe penalties for those found to be in violation of the established rules. The threat in many countries comes from laws that are ostensibly designed to protect national security or citizens from cybercrime, but which are so broadly worded that they can easily be turned on political opponent.”

Tito Sotto may not get it. But, fortunately, many Filipinos do.

On Twitter @BoyingPimentel. On Facebook at www.facebook.com/benjamin.pimentel