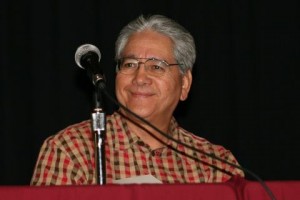

Filipino American writer with a Waray soul

SAN FRANCISCO – Born in Leyte and raised in Manila, Oscar Penaranda remembers a happy and glorious childhood.

But then his family left for the United States. That was several decades ago — Oscar still hasn’t gotten over it.

“After I left the Philippines, I was bitter. I was angry, and I’ve been like that ever since,” he told me in an interview a few years ago for Pinoy Pod program of the San Francisco Chronicle.

“It was really the best times of my life. I’m waiting for something else to make me a little less skeptical. I’m very skeptical about a lot of things. Friendship – I’m skeptical of it. Permanence, I’m skeptical of it because I was uprooted, I thought, from the glory and happiness of my childhood. I was taken away by my parents to live here in America. Until now, I’m a little bit bitter about that – because I never really accepted living in America as my home and natural place.”

Still, despite all that bitterness, the US and the Philippines have somehow found a natural place for Oscar.

He is one of the most admired Filipino American writers in the Bay Area where he also is an educator and activist. He returns to the Philippines frequently.

He was home just recently, in fact. Last week, Oscar Penaranda received the prestigious Gawad Pambansang Alagad ni Balagtas Award from the Unyon ng mga Manunulat sa Pilipinas (Umpil).

The award has typically gone to Filipino writers based in the Philippines. A few Filipino Americans have been honored, such as Bienvenido Santos. Now, Oscar Penaranda, one of today’s most accomplished Filipino American poets and fiction writers, has joined the list.

It’s a well-deserved honor. The award also caps a fascinating journey of a young kid from Leyte where he says he still draws much of his material.

“My Waray I never forgot,” he said, noting that he speaks it without an accent. Leyte, he added, provided him with what he called “the ancestral subconscious.”

“I must have drawn a lot form it subconsciously,” he said. “I was born by the sea coast. I would get up in the morning and I’d swim right away.”

Manila, where he spent his boyhood years, is also a place he remembers with fondness. Some images from the memories may be hard for some to take nowadays. Such as the cover photo of the old Philippines Free Press which Oscar said featured him and other children. They were naked, swimming in Manila Bay.

He may sound like he never learned to fit in. But Oscar is an institution in the Filipino American community. He was a founder of the San Francisco chapter of the Filipino American National Historical Society and helped spearhead the Filipino American Jazz Festival in San Francisco.

He has taught high school and college students in the Bay Area. In fact, he took part in the famous strikes in the 1960s that paved the way for the introduction of Ethnic Studies courses on college campuses.

Oscar is best known as a poet and short story writer, and for his books, the poetry collection, “Full Deck,” and “Seasons by the Bay,” a collection of stories.

Many of the stories refer to his childhood and the life he left behind. They’re not always uplifting tales. There’s violence and bigotry. We asked him about that on the program. He made it a point “to counter” his nostalgic feelings, he said.

“When a writer or artist feels nostalgic about something,” Oscar explained, “it’s good for that artist to check himself or herself, and not indulge in pure nostalgia because pretty soon you’re just indulging in what makes you feel good and you’re forgetting the reality of the people who live there.”

He has sought to reconnect with that reality in his own way. One recent trip to his native Leyte even made him see a way to reconnect with his native tongue, Waray.

He was with a group of Filipino American writers visiting UP Tacloban. The visitors from the US read from their work. One of them, the activist Vangie Buell, read from her moving autobiography Twenty Five Chickens and a Pig for a Bride, about growing up in Oakland as the granddaughter of a Filipina immigrant and an African American who served during the Philippine-American War.

“The audience was pleasantly and proudly astonished,” Oscar recalled. They told him: “We have never heard anything like this before — not in our institutions, not through our relatives, not in the newspapers, not in TV and movies, nowhere.’”

Oscar clarified that in the US Filipino American literature is still also “at the fringes and most of the time no one has ever heard of these stories, either, especially in the mainstream.”

One of the Leyte professors, Voltaire Oyzon, responded: “We have a similar problem here. Here our stories and our language Waray hardly get any play. What are in the institutions are either English or Tagalog. Our Waray language is rarely used, and consequently in a couple of generations, will disappear.”

Oscar was struck by the comment, and made him focus some of his energies on preserving his first language.

He helped set up and raise money for a literary contest for Waray writers. His group is even encouraging writers to translate Filipino American works into Waray and “perform them in universities and public places, in cities, marketplaces, fiestas, talent shows, sports tournaments, all around the countryside.”

For Oscar, it was another chapter in his journey as a kid who was uprooted from his homeland and is now a writer seeking ways to tell his stories.

“The Philippine literary scene I did not discover until I already well into my writing,” he told me. “I have been brought up by learning nothing but white (and a few black) writers and to me it served as an incentive because I keep telling myself: they are not telling my stories, our stories as a people, my mother’s stories, my auntie’s and my uncles and my father’s stories. The‘mainstream’ cannot be my path. I and other like me must strike our own paths. And this path we called Filipino American Literature.”

On Twitter @KuwentoPimentel. On Facebook at www.facebook.com/benjamin.pimentel