Chinese and Filipino in the world of dangerous stereotypes

The first report from Forbes Magazine is about the top billionaires in the Philippines. It’s a list that many noted is dominated by Filipinos of Chinese descent.

A Philippine Daily Inquirer headline read “Ethnic Chinese dominate PH economy.” It was among the most read pieces of that week – and it made me uncomfortable.

It was mainly because of the stereotype it evoked. And stereotypes, though they may be innocent or unintended, make me nervous. At a time when war is possible, they should make us all nervous.

The column could easily be misread as saying: “They’re not only claiming our islands, they even own our economy.” Some of that resentment bubbled up, in fact. “They count money every day,” one reader’s comment said, affirming that sinister portrait of the Chinese.

The resentment is not surprising given what’s been happening.

Article continues after this advertisementGiven the stunning reach in terms of territory that the country’s gigantic neighbor to the north is claiming, Beijing sure is coming across as a bully. It’s a perception shared increasingly by other nations in Southeast Asia.

Article continues after this advertisementWhat’s probably surprising to some is that Beijing doesn’t seem to care. But perhaps that shouldn’t be surprising, because clearly Beijing is primarily concerned with what one particular group thinks: the Chinese.

Take note that I say ‘Beijing.’ That is, the Chinese government, or more precisely the Chinese Communist Party.

For in the conflict over the islands in the South China/West Philippine Sea, we’re not really talking about the ordinary Chinese or the ordinary Filipinos.

Based on news reports, even the Chinese and Filipinos fishermen in the disputed waters actually managed to get along before the military and political muscle flexing heated up.

Still, as these conflicts typically go, the dispute has morphed into a nation-against-nation dispute, into a Filipino vs. Chinese showdown.

I suspect Beijing’s spin, aimed squarely at the ordinary Chinese, pretty much goes like this: ‘Worry not comrades for China is courageously standing up to that big bully called the U.S.A. represented by that pesky little island nation.’

So while the Philippines is painting the Chinese as the big siga by using its bigger more powerful navy to muscle its way into a bigger slice of the South China/West Philippine Sea, Beijing is painting the Filipinos as the sidekick of an even bigger siga which has long played a controversial, even unpopular, role in the region.

Shifting focus eastward across the Pacific to the United States, there’s the other report which also has created a stir.

The Pew Research Center put out a study titled “The Rise of Asian Americans.”

It’s an upbeat report, touching on the state of the two giants of that community: the Chinese, the largest Asian population in the U.S., and the Filipinos, the second largest.

The study really should make Filipino Americans, Chinese Americans and all Asian Americans happy. For the report says they are, well, happier, richer (have higher incomes) and smarter (have more education.)

Great news, right? Well, not exactly for many Asian Americans. And having once covered Asian American affairs for the San Francisco Chronicle many years ago, I understand why.

For here we have another set of stereotypes, another example of spin or the potential for spinning.

The report’s message is not new. Asians have long been portrayed as the ‘good’ or ‘ideal’ minorities: They study hard. They work hard. They make a good living.

The model minority.

The Chinese, in particular, have been painted this way. And I have Chinese American friends who reject that portrait – for it has a quirky downside: It’s been typically used to paint other communities, mainly blacks and Latinos, as the ‘bad’ minorities.

Paul Igasaki was vice chair of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission when he told me that “the concept of the model minority is as much a message to other minorities as it is a statement about us.”

“To say that we are a model minority is to say that other minorities are not so hot. It’s very misleading,” he said.

There’s also the tricky side note in this portrait – it paints Asian Americans as obedient, pliant workers, to the point of being submissive and easy to control. That’s why it wasn’t surprising to hear some Asians react: ‘Here we go again. We’re the model minority again.’

Two sets of stereotypes on both ends of the Pacific.

In Asia, they pit Filipinos and Chinese against each other.

In America, they led Filipinos and Chinese to stand side-by-side to reject stereotyping.

Occasionally that alliance led to meaningful change and victory. Earlier this year, Ed Lee became the first elected Asian American mayor of San Francisco.

Among those who cheered Lee, who is Chinese American, was a Filipino American, lawyer Bill Tamayo.

They were veterans of big battles for Asian American civil rights in the 1980s. In fact, as Tamayo told the San Francisco Chronicle, there was a time when he even gave up part of his $600-a-month salary to support Lee who delayed taking the bar exam so he could work on a rent strike their group had endorsed.

Affordable housing was a big deal, and still is, for many lower income Filipino and Chinese immigrants in San Francisco.

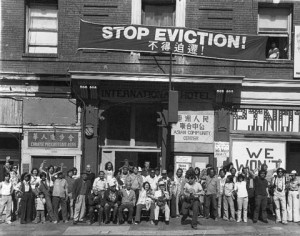

Thirty five years ago, in 1977, a group of elderly Filipinos and Chinese men, mostly poor immigrants, fought back shoulder-to-shoulder, supported by young Filipino and Chinese activists, to resist the demolition of their home, the International Hotel.

They failed. The old people got kicked out of their home. But that struggle is still remembered as an activist milestone in San Francisco.

Such acts of solidarity were not surprising. And struggles for civil rights, and against stereotypes, defined the stories of both the Filipino and the Chinese in America. In many cases, their journeys merged into one.

They probably saw it as the only way forward. They had to act, and to act as one, often in solidarity with other Asians, and other minority communities.

For in the US, like in other places, including Southeast Asia, stereotypes can be dangerous. They can even get you killed.

That happened 30 years ago. In 1982, a young man in Detroit named Vincent Chin was beaten to death with a baseball bat by an unemployed auto worker.

The auto worker was white. He was upset by the tremendous success of the Japanese auto industry which he believed cost him his job. So he took his frustration out on Chin — who was actually Chinese.

It’s worth repeating: stereotypes are dangerous.

“Perceptions can lead to resentment. And resentment can lead to hate,” the Chinese American legal scholar Frank Wu wrote in New York Times in a piece marking the 30th anniversary of Chin’s death.

He could very well have been talking about the situation the Philippines and China find themselves in.

For shifting the focus back to Southeast Asia, as we wait to hear what really happened to the Filipino fishing boat that ended up capsizing in the disputed waters, it’s worth remembering — and repeating: Stereotypes are dangerous.

On Twitter @KuwentoPimentel. On Facebook at www.facebook.com/benjamin.pimentel