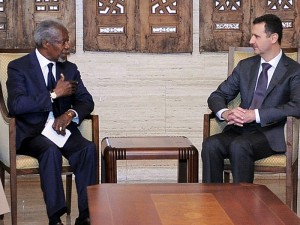

- In this photo provided by the Syrian official news agency SANA, Syrian President Bashar Assad, right, meets with Kofi Annan, the U.N.-Arab League Joint Special Envoy for Syria, in Damascus, Syria. The meeting Tuesday followed a massacre in Houla, Syria, last week in which more than 100 people were killed, some of them women, children and entire families gunned down in their own homes. Following the meeting, Annan told reporters “We are at a tipping point.” (AP Photo/SANA)

BEIRUT — Eyewitness accounts from the Syrian massacre are emerging, describing shadowy gunmen slaughtering whole families in their homes and targeting the most vulnerable in poor farming villages. Western nations have expelled Syrian diplomats in a coordinated move against President Bashar Assad’s regime over the killing of more than 100 people.

U.N. special envoy Kofi Annan met with Assad in Damascus on Tuesday to try to salvage what was left of a peace plan, which since being brokered six weeks ago has failed to stop any of the violence on the ground.

Survivors of the Houla massacre blamed pro-regime gunmen for at least some of the carnage as the killings reverberated inside Syria and beyond, further isolating Assad and embarrassing his few remaining allies.

“It’s very hard for me to describe what I saw, the images were incredibly disturbing,” a Houla resident who hid in his home during the massacre told The Associated Press on Tuesday. “Women, children without heads, their brains or stomachs spilling out.”

He said the pro-regime gunmen, known as shabiha, targeted the most vulnerable in the farming villages that make up Houla, a poor area in Homs province. “They went after the women, children and elderly,” he said, asking that his name not be used out of fear of reprisals.

Assad’s government often deploys fearsome militias that provide muscle for the regime and carry out military-style attacks. They frequently work closely with soldiers and security forces, but the regime never acknowledges their existence, allowing it to deny responsibility for their actions.

U.N. peacekeeping chief Herve Ladsous said there are strong suspicions that pro-Assad fighters were responsible for some of the killings, adding that he has seen no reason to believe that “third elements” — or outside forces — were involved, although he did not rule it out.

The Syrian regime has denied any role in the massacre, blaming the killings on “armed terrorists” who attacked army positions in the area and slaughtered innocent civilians. It has provided no evidence to support its narrative, nor has it given a death toll.

Following his meeting with Assad, Annan called on the government and “all government-backed militias” to stop military operations and show maximum restraint. He also called on the armed opposition to stop all violence.

“We are at a tipping point,” Annan told reporters in Damascus. “The Syrian people do not want the future to be one of bloodshed and division.”

Cranking up the pressure on Assad, the Obama administration gave Syria’s most senior envoy in Washington, the charge d’affaires at the Syrian Embassy, 72 hours to leave the United States. Britain, Canada, Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Bulgaria also expelled Syrian diplomats.

“We hold the Syrian government responsible for this slaughter of innocent lives,” State Department spokeswoman Victoria Nuland said in Washington. “This massacre is the most unambiguous indictment to date of the Syrian government’s flagrant violations of its U.N. Security Council obligations.”

The massacre in Houla could prove to be a watershed moment in the Syrian crisis, which began in March 2011 with peaceful protests inspired by the wave of uprisings sweeping the Arab world.

Nearly 15 months later, the country is in many ways unrecognizable from the days before the revolt. Assad, once considered a potential reformer in a region filled with aging dictators, is a global pariah. A country that once boasted it was the safest in the Middle East is riven with violence, some of it reminiscent of the worst days of the Iraq war. The economy is in tatters. Syrians are facing price increases for basic goods and endure regular power cuts.

And in some haunting cases, neighbors who have lived side by side for years are turning on each other, driven by sectarian hatred that so many months of violence is laying bare.

According to witnesses, the massacre, which began late Friday in an area about 40 kilometers (25 miles) northwest of the city of Homs, had dangerous sectarian overtones.

The victims lived in the Houla area’s Sunni Muslim villages. But the shabiha forces allegedly behind many of the killings came from an arc of nearby villages populated by Alawites, an offshoot of Shiite Islam.

Most shabiha fighters belong to the Alawite sect, to which the Assad family and the ruling elite also belong. This ensures the gunmen’s loyalty to the regime, built on fears they will be persecuted if the Sunni majority gains the upper hand.

Sunnis make up most of Syria’s 22 million people, as well as the backbone of the opposition. Even as much of the opposition insists the movement is entirely secular, disturbing reports from the ground suggest religious tensions are boiling over.

The volatile sectarian divide makes civil war one of the most dire scenarios.

Activists say as many as 13,000 people have been killed in the uprising. The U.N. put the toll at 9,000 as of March — one year into the revolt — but many hundreds more have died since.

On Tuesday, the U.N.’s human rights office said most of the 108 victims of the Houla massacre were shot at close range. The U.N. report indicated that most of the dead were killed execution-style, with fewer than 20 people cut down by regime shelling.