What’s at stake in PH-China standoff

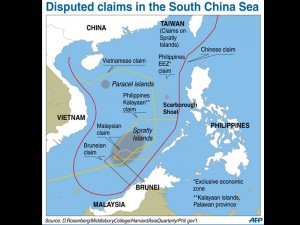

Map showing the disputed areas in the West Philippine Sea (south China Sea), including the Spratlys Islands and Scarborough Shoal. AFP

It started like many other minor confrontations over the specks of isles dotting some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. But the risks in the latest flare-up over a South China Sea shoal are much bigger than the territory itself.

Armed vessels from the Philippines and its much more powerful neighbor, China, have faced off for two weeks at the horseshoe-shaped Scarborough Shoal. Either side could miscalculate—and consequences could bear down on the whole region, and drag in the United States, too.

Here’s a look at the key players, issues and what’s at stake:

How it started

The Philippine Navy says it caught Chinese fishermen poaching, and on April 10 two Chinese vessels moved in to protect them. The fishing boats slipped away, leaving behind a tense standoff with each side hoping the other will pull out first.

History of flash points

The shoal, which the Philippines calls Panatag Shoal, is among 200 islands, coral outcrops and banks spread over the South China Sea—called by the Philippines West Philippine Sea—with rich fishing grounds and other resources. The biggest of them are the Spratlys, claimed all or in part by the Philippines, China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Brunei and Vietnam.

There have been sporadic shoot-outs at sea in the past few decades—China-Vietnam, China-Philippines, Taiwan-Vietnam and Philippines-Vietnam—with navies sinking ships and fortifying disputed islands. A major clash in 1988 between China and Vietnam killed 64 Vietnamese soldiers. China took over the Philippine-occupied Mischief Reef in a surprise mini-invasion in 1995.

Then in 2002, all parties agreed to a status quo.

It largely held. Until now.

Political context

Last year, Manila accused Chinese vessels of blocking its energy exploration ships in Philippine waters and firing to scare away Philippine fishermen.

It was just a year after President Aquino took office promising to fight corruption and restore national dignity. His predecessor, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, was accused of cozying up to Beijing and corrupt deals with Chinese investors. Contracts were scrapped, and Aquino turned to the country’s traditional ally, the United States, just as US President Barack Obama sought to reengage in Asia.

On the other hand, China—as a rising economic and military power—is asserting territorial claims and in no mood to show weakness.

Overlapping claims

Scarborough Shoal lies within Manila’s 370-kilometer (230-mile) exclusive economic zone, recognized under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. But China says the Philippines is misinterpreting the law. Beijing’s position is based on ancient maps, though it’s unclear how much weight they carry today.

China’s map submitted to the United Nations in 2009 claims virtually the entire South China Sea, but Beijing has failed to clarify the exact extent of its claims. It turned down a Philippine invitation for international arbitration.

US role

Manila feels—and so does China—that the Philippines has US backing.

That’s true up to a point.

The United States is obligated to defend the Philippines from outside aggression under a defense treaty, and has close ties with Manila’s security forces in their fight against southern Muslim militants. Recently, Washington has helped modernize the poorly armed Philippine forces, particularly the Navy.

Washington angered Beijing in 2010 when it declared that unimpeded commerce and resolution of disputes in the South China Sea are in the United States’ interest.

But the United States—with ever-increasing economic ties to China—has always maintained it is not taking sides.

Gas and oil factor

Some of the tensions involve competition for petroleum. It isn’t clear, however, how much the region holds and most published surveys suggest little evidence of substantial reserves apart from natural gas.

The overlapping territorial claims make exploratory drilling difficult.

The Philippines’ Malampaya and Camago fields, containing up to 4.4 trillion cubic feet (1.3 trillion cubic meters) of natural gas, are in waters claimed by China. Still, Manila has developed the fields and built a pipeline that already delivers gas that has become vital to its economy. But a Philippine plan to invite bids to explore two other areas has drawn strong Chinese protests and fears of escalating confrontations. AP