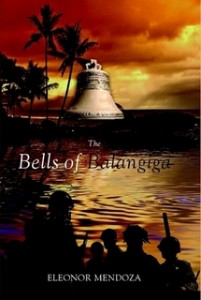

In an exclusive interview with the Asian Journal, the new author from Davenport, Iowa said, “My maiden name is what I use as a professional name: Eleonor Mendoza. I also use my married name: Eleonor Mendoza-Gonzales. I’m a traditional Filipino-American, proud of a lot of good Filipino traits, and a lot of traditions that define what we are. We should keep them and find strength in them.”

Eleonor showed the effects of war in the lives of people in her new novel. “We talk of countries going to war, but it is the people who go to war, who fight, who lose loved ones, who are killed,” she says. “The Bells of Balangiga shares two stories of people who fall in love, against the backdrop of human conflict.”

Balangiga bells: War booty

One can better appreciate The Bells of Balangiga if he knows the significant role the bells played in Philippine history. The Balangiga bells are three church bells taken by US forces from the town church of Balangiga, Eastern Samar in the Philippines as war booty in retaliation for an earlier ambush they suffered at the hands of Filipino soldiers during the Philippine-American War.

According to Veltisezar Bautista in The Balangiga, Samar Massacre, (via Wikipedia) Filipino freedom fighters from the village of Balangiga ambushed Company C of the 9th US Infantry Regiment, while they were at breakfast on September 28, 1901–killing an estimated 48 and wounding 22 of the 78 men of the unit, with only four escaping unhurt. In reprisal, General Jacob H. Smith ordered that Samar be turned into a “howling wilderness” and that any Filipino male above 10 years of age be shot. From the burned-out Catholic town church, the Americans took the three bells as war booty.

Seed of enmity

Dr. Mendoza admitted to Asian Journal that she was unaware of this incident, like many Filipinos.

Reading about it inspired her to write her first novel. “My attention had been caught by a Wall Street Journal (WSJ) article that told of the massacre in Balangiga during the Philippine Insurrection. The WSJ article mentioned that the Philippine Government was requesting the return of the ‘Bells’ that were taken as war booty by the Americans to avenge the massacre of their comrades,” recalled Mendoza.

“Until I read that WSJ Article, I was not aware of that incident. The bells of Balangiga caught my interest. I learned that a controversy had arisen when the Philippine government requested the return of the ‘bells’ from Warren Air Force Base in Wyoming.”

“The old US Veterans refused to give it back and their Congressmen and other politicians were involved. Previous requests from nationalistic Filipino groups for a return of the ‘bells’ had been turned down. What struck me when I read more about the issue is the disproportionate punishment that was meted out not only to the rebels but to the entire town. This was a study of military history in itself, the consequence of an act not thought out to the final conclusion, the unforeseen factor of overreaction and bias, and in the end, that there are good people and bad people,” said Mendoza.

The conflicts of war

The Bells of Balangiga takes place in the Philippines, and reflects the customs, traditions, and charm of the time. The story is set with Lieutenant Jack Stewart, a West Point graduate assigned to the Nueva Ecija Province in the Philippines in 1940. Jack falls in love with a young Filipina woman named Neneng, but when his parents visit to attend a reception for the officers, Jack’s mother reveals that Jack has a sweetheart back home.

Crestfallen, Neneng seeks comfort in the arms of her mother Clara, who divulges that she was once engaged to Jack’s father during the Philippine Insurrection (1899-1902). Since then, Clara has been haunted by the sounds of the bells of Balangiga, three church bells taken by the United States Army from the Philippines in 1901. To her, they embody the conflict that shaped her early life.

The author admitted that she herself has been shaped by conflicts from war. In World War II, guerilla soldiers took Dr. Eleonor Mendoza’s father, also a physician, to care for their sick and wounded. Meanwhile, her mother and older siblings were forced to evacuate to the mountains, where they formed a community with other guerilla families.

Though Dr. Mendoza would not be born until after the conflict ended, she says, “War always had a presence when I was growing up. My older siblings, the elders, the servants – they often referenced it in their conversations and, for me, it became a part of life. I grew up with all the ‘war talk’ as though it was recent. My brothers would show the younger ones the books with the dog fights, the air craft carriers, the generals, the armies, and bomb out ruins. The maid would play tricks on them and say, “Dock! The Japanese are coming!” We would hide for quite a while before she says, “It’s all clear.” We stayed away from big trees where the guerillas had been hanged,” she recalled.

Origins, education and career