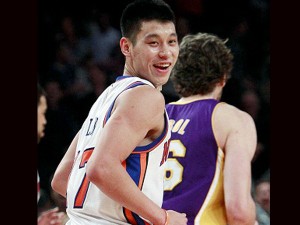

Jeremy Lin reacts after scoring during the first half of an NBA basketball game against the Los Angeles Lakers, in New York on February 10. AP

San Francisco—It’s an inspiring underdog story, a tale of the triumph of determination.

But certainly one reason Jeremy Lin’s story has become a big deal is the fact that he’s Asian American.

That was why there was excitement in the Bay Area Asian American community when Jeremy Lin joined the Golden State Warriors two years ago.

I thought back then that I’d finally get my son interested in basketball (he’s more into baseball) and we’d catch games at the Oakland Arena, a short train ride from our house.

But we never got around to doing that. And just like that Lin was gone. He ended up with the Houston Rockets before joining the New York Knicks. It seemed as if he would fade into oblivion.

But suddenly it hit: Linsanity.

Who wouldn’t be thrilled by the sudden, spectacular rise of a young kid who finally got a chance to shine?

But then, a shrill noise from someone very familiar to Filipinos.

“Jeremy Lin is a good player but all the hype is because he’s Asian,” went Floyd Mayweather’s tweet. “Black players do what he does every night and don’t get the same praise.”

By now, we’re used to him, of course.

This is the same guy who has repeatedly insulted Manny Pacquiao using racist, homophobic language. Mayweather had proudly declared that he was “going to cook that little yellow chump” and would “make that mother-(bleep) make me a sushi roll and cook me some rice.”

On Lin, Mayweather’s rants simply did not make any sense.

Lin’s an excellent player. But Mayweather thinks all the excitement is simply because he’s Asian?

Well, he conveniently missed the other part of the story: that the fact that Lin’s an Asian American was most like a factor why he got noticed only recently.

And what about Mayweather’s remark that black players “don’t get the same praise?” What’s he talking about?

African American players are recognized as among the best in basketball and in other sports.

In fact, for the broader African American community, that has even become a problem in a way. For they have fallen victim to a cruel stereotype—one that says sports is the only arena where blacks can excel.

I covered the Asian American affairs beat for the San Francisco Chronicle in the early 1990s and have encountered the prejudices the Asian American and African American communities have had to wrestle with.

While covering the aftermath of O.J. Simpson’s arrest, I met an off-due black cop outside Simpson’s home who lamented that African Americans are generally viewed as being able to shine only as athletes or entertainers.

And it’s a kind of corrosive prejudice that Mark Dean had to contend with.

Dean’s one of the most respected technologists in the United States, considered a pioneer in Silicon Valley who headed IBM’s famous research lab in what’s known as the Mecca of technology.

He also happened to be African American. But his lighter complexion made some people wonder if he’s indeed black – and, sadly, so did the fact that he’s such a brilliant guy.

As Dean told me a few years ago, a friend of his, who was white, once asked him: “You’re not black, are you? You get good grades and you do these things—and black people don’t do that.”

Dean simply said, “’I am black and we can do these things.”

“This was depictive of the attitude of what blacks could and couldn’t do,” he told me.

Asian Americans have had to struggle with a different set of prejudice: one that portrays them as the model minority.

It assumes that all Asians will excel in academics, that they are extraordinarily good in math and science, that they are reliable and hard-working—but also generally unassertive. They may be good middle managers, but not good enough to be the boss. And they almost certainly cannot be expected to shine in the world of sports. (Well, maybe in karate, Kung Fu or ping pong.)

These twisted images of blacks and Asians are rooted in history, as law professor Frank Wu explained to me in the early 1990s.

After the Civil War, public figures and officials, still annoyed by the end of slavery, portrayed immigrant Chinese workers as being more obedient and industrious than the newly freed slaves whom they replaced on plantations in the South.

These prejudices reemerged in the 1990s in the fight to dismantle affirmative action programs meant to open up more opportunities for minorities.

In these battles, Asians were pitted against blacks. This became objectionable to many Asian Americans, like Wu.

As he complained to me at the height of the affirmative action battles back in the 1990s, “I don’t want to see myself or my life experiences or the example of Asian Americans used to further divide people. I don’t want people pointing at me and saying, `Hey, look, you Asian Americans are doing well—why can’t African Americans do well, too?’”

Fortunately, some of these attitudes have started to break down. Yao Ming was one example. The rise of Jeremy Lin marks another important chapter.

Hopefully, 20 years from now, having an Asian American star player in the NBA or other leagues will no longer be such a big deal.

But it is today, which is why Lin’s spectacular performances have drawn much attention in the U.S. and abroad.

Lin has made history. And the fact is, despite Mayweather’s incredibly narrow viewpoint, it’s a history in which African Americans played a critical role.

That Lin exploded on the sports scene this year is significant for another reason.

This year marks the 65th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s debut as a major league baseball player, when he broke the color barrier in the popular American pastime.

In a way, the Jeremy Lin story can be traced back to that chapter in American history.

As the first African American to play in major league baseball, Robinson faced tougher, even more dangerous challenges. That’s because there were people blinded by prejudice who really wanted him to fail.

Robinson blazed the trail for people like Lin. So did the others who came after him — including Hank Aaron and Muhammad Ali – athletes who made it easier and even possible for non-whites to enter and even shine in the world of American sports.

Some of the pioneers were also Asian Americans.

Like Wat Misaka, the Japanese American who became the first non-white to play in the NBA in the late 1940s. In the 1970s and 1980s, there was Filipino American Raymond Townsend.

These are historical connections that Mayweather is clearly too arrogant to understand.

Still, Mayweather’s own career does offer one important insight. He keeps bragging about his undefeated record.

Well, now we know that it is entirely possible for a sports figure to build an undefeated record — and still end up a loser.

On Twitter @KuwentoPimentel. On Facebook at www.facebook.com/benjamin.pimentel