MacArthur and Private Moon: Rebels for a cause

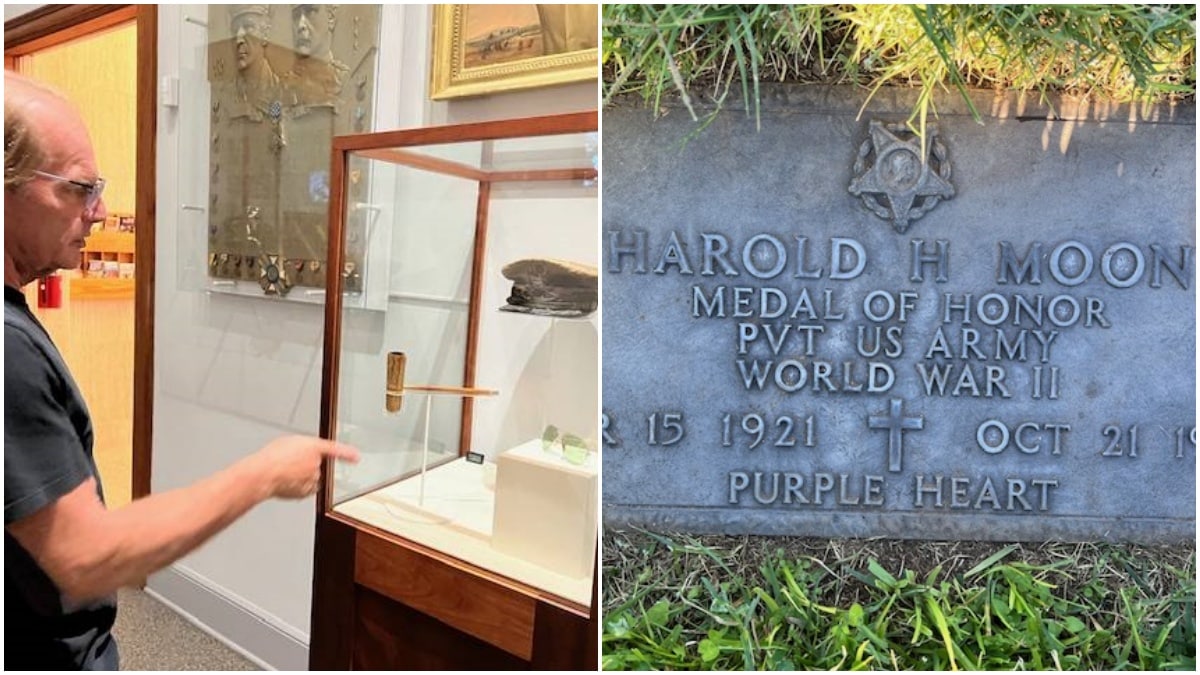

AMERICAN HEROES James Zobel, chief archivist of MacArthur Memorial in Norfolk, Virginia, points at the iconic pipe, peaked cap and Ray-Ban that defined Gen. Douglas MacArthur; the tombstone of Pvt. Harold Moon Jr. in his home state of NewMexico. Moon was killed in a suicide attack by Japanese soldiers as US forces led by MacArthur advanced in Leyte to liberate the Philippines 80 years ago on Sunday. —Photos by Danny Petilla

(Last of two parts)

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA, United States — Among the bits of memorabilia inside the museum honoring Gen. Douglas MacArthur here is the infamous April 11, 1951, letter of termination from President Harry Truman, effectively ending the general’s military career.

Placed inconspicuously on the wall on the second floor of the MacArthur Memorial, this document is proof that the imperious MacArthur fought with his superiors from President Franklin Roosevelt to Truman, even as America waged wars against Japan and in Korea from 1941 to 1952.

READ: SPECIAL REPORT: Stealing MacArthur’s thunder

On Oct. 2, this reporter flew couch on United Airlines Flight 3716 from Newark International Airport in New Jersey to Norfolk International Airport in Virginia.

As the Boeing 737 descended from patchy clouds into Norfolk, I could see the strength of America’s naval power sprawled on the mighty Chesapeake Bay.historical

But I am not here in Norfolk—home of the world’s largest naval base—to ogle at hulking aircraft carriers and submarines.

Four-hour firefight

I am here in search of answers about the legend of an American soldier whose death and martyrdom in my Philippine hometown in 1944 helped defeat the Japanese invaders toward the end of World War II.

James Zobel, the museum’s chief archivist, was happy to meet a visitor from the small town in Leyte where MacArthur and thousands of his troops splashed ashore 80 years ago this Sunday.

“We are glad to have you here,” Zobel said as he showed me a glass-covered box that contained three iconic items that defined MacArthur: his oversized corn cub pipe, the modified crush cap and, of course, the Bausch & Lomb Ray-Ban Aviator.

Eighty years ago, after the news of MacArthur’s return to the Philippines had spread around the world, the fierce battle between a 23-year-old American soldier named Pvt. Harold Moon Jr. and a horde of Japanese enemy combatants had yet to unfold.

What happened next would sear the minds of those who witnessed it.

Crack troops from the 16th Japanese Imperial Army under Lt. Gen. Shiro Makino kept tossing grenades into his foxhole. Moon would pick them up and hurl them back to the enemy, killing them in droves.

“C’mon you yellow sons of bitches! C’mon and fight,” Moon taunted the attackers, killing an English-speaking Japanese officer with his Thompson submachine gun.

In an intense four-hour firefight worthy of a Netflix movie, Private Moon engaged literally in the fight of his life on Oct. 21, 1944, before falling to a bayonet charge by a Japanese suicide platoon.

Two days later, MacArthur stood in front of the massive columns of the American-built Leyte Capitol. He did not speak about Private Moon. Instead, he praised Ruperto Kangleon, the leader of the Filipino guerrillas in Leyte.

But in toasting Kangleon’s leadership, MacArthur did not say a word about the thousands of Filipinos that lay dead in nearby Dulag town, all tragic victims of the Americans’ massive carpet bombing two days before he and his troops arrived in Leyte.

Still, the troops were restless. They were shocked and awed at Moon’s incredible gallantry. The locals came out of hiding from the hills and the woods to embrace Moon’s heroics. News of Moon’s epic kills had spread like wildfire.

With his forces depleted and his country burning and in ruins from the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki days earlier, General Makino killed himself in Leyte on Aug. 10, 1945, rather than surrender to the Americans.

Upstaging MacArthur

“Homeric incredibility,” was the description used by combat reporter Richard Krebs, who traveled with Moon’s battalion in Leyte.

Using his nom de guerre, Jan Valtin, Krebs evaded the military sensors and wrote the definitive story of the 24th Infantry Division’s operations in Leyte in his 1945 book, “Children of Yesterday.”

I asked the amiable Zobel if he knew of anything in MacArthur’s massive archives that would add to the legend of Private Moon. Zobel said he didn’t.

But he knew Maj. Gen. Aubrey Newman, commander of the 34th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division. It was Newman, then a colonel, who made the fateful decision to pull Moon—a perennial troublemaker—out of the stockade and send him to fight in the front lines.

Private Moon, the troublemaker and “screw-up of Company G,” had upstaged the larger-than-life persona of the egotist MacArthur.

“The name of Private Harold Moon, that truly unforgettable soldier, is remembered again and again, with respect and admiration,” Newman wrote in 1974 as he reminisced about his decisive recommendation to give Private Moon America’s highest military award.

Private Moon would get his moment of glory posthumously when Truman presented the Medal of Honor to his family on Nov. 15, 1945, making him the first soldier from New Mexico to get that distinction.

But the rebellious Moon also shared a common trait with his commander, MacArthur. They both defied their superiors.

Despite being on opposite poles of the military hierarchy, both men received America’s highest military award.

Ironically, MacArthur received his on March 25, 1942, while in Australia during the dark days of the Pacific War, while Filipino and American soldiers were dying by the thousands.

It would not be surprising that on Sunday’s 80th commemoration of the A-Day Landing in my hometown of Palo, Leyte, officials would say words of praise about MacArthur.

Honored in Japan

Organizers have chosen the theme “Yesterday’s Heroes, Today’s Inspiration for the New Generation.”

But would these officials say one word about Private Moon’s heroism?

New Mexico military historian John Taylor wrote that Moon was even honored in the land of his enemies.

“A theater in Okayama, Japan, was renamed in his honor,” Taylor said in his 2023 book “A Legacy of Heroism.”

Maj. Gen. James Lester, commander of the 24th Infantry Division, named the Harold H. Moon Theater to honor the soldier’s valor in “almost single-handedly breaking up a Japanese counterattack on the newly won beachhead at Leyte.”

Dying from liver cancer and a failing kidney in March 1964, MacArthur struggled to write the book “Reminiscences”—the only one he wrote himself—to reflect on his legacy and impact in history.

“It is my hope that it will prove of some interest to the rising generation, who may learn that a country and government such as ours is worth fighting for, and dying for, if need be,” wrote MacArthur.

On April 5, 1964, MacArthur died at age 84.

Private Moon died living by MacArthur’s mantra. And it was a glorious death. —contributed