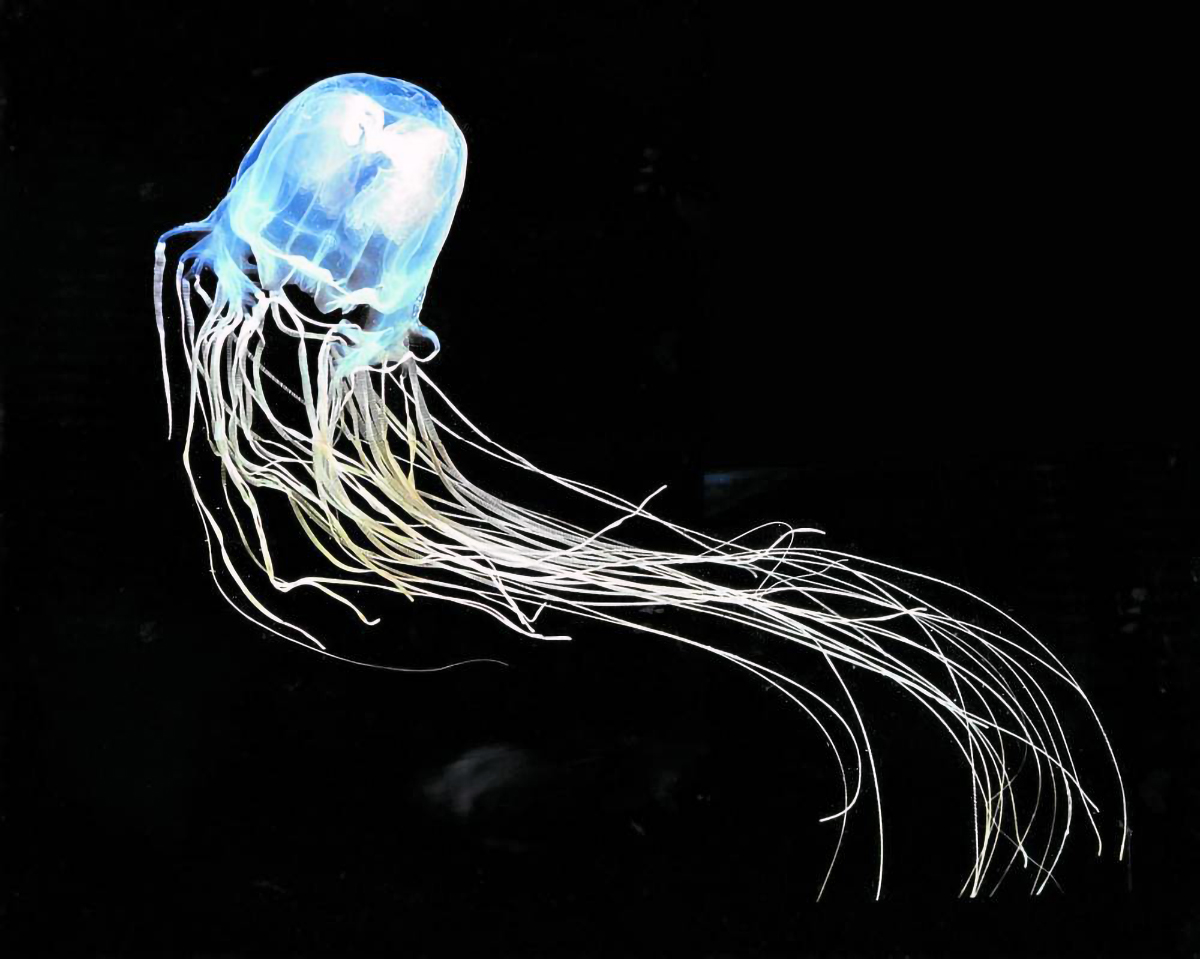

DEEP DIVE INTO A SAFETY CONCERN Hawaii-based biochemist Angel Yanagihara has made the study of jellyfish stings a lifelong pursuit, one that has sent her several times to the Philippines where she hopes to raise awareness and inspire more government action on an underreported health and safety concern. Her constant subject is the deadly box jellyfish. When not reaching out to coastal communities, she goes on a deep dive to collect samples for her continuing research. —photos by Dr. Robert Harwick, Laura Aguon and Keoki Stender, University of Hawaii Dive Safety Office

MANILA, Philippines — While most people travel to the Philippines to relax and party on its scenic coastlines and famous beaches, biochemist Angel Yanagihara is drawn to these parts by something that can ruin any swim or wade in the surf.

A world-renowned expert in jellyfish sting—or envenomation, the more technical term of her field—Yanagihara has been campaigning in the country for a more coordinated effort to document and respond to injuries or fatalities caused by the deceptively passive marine creatures.

“[The Philippines] is actually Ground Zero for this health burden,” said Yanagihara, an associate professor from the University of Hawaii at Mānoa’s Department of Tropical Medicine. “All the most lethal species are here … [but] there has been no professional database or some sort of recordkeeping.”

The dearth of attention given to this concern grew starker for Yanagihara when she learned about the case of two children, age 3 and 7, who died in Talao-talao in Lucena City, Quezon province, last month after being stung by a box jellyfish, a highly toxic variety, as they swam in the shallow waters.

The stings appeared as dark red lashes on the children’s skin, the venom enough to cause cardiac arrest.

The two deaths hardly made it to the news, but they broke Yanagihara’s heart when she heard about them upon arriving on her latest trip to the country. This was because the biochemist went to the same town in 2018 to study box jellyfish, which then also killed an 18-month-old boy.

Moved by the toddler’s death, Yanagihara started giving talks to the local village officials, met with disaster management officers and gave them some lifesaving first-aid supplies for their use.

“Even though we’ve been there again and again and we’ve done a lot of work, we haven’t done enough,” she told the Inquirer in a recent interview.

Angel Yanagihara, arguably the world’s foremost expert on jellyfish envenomation, in her office in the University of Hawaii. —Laura Aguon

The hardest part

Yanagihara has spent much of her life studying and making seminal discoveries on jellyfish venom and how it attacks the human body.

“But as it turns out, I thought the science was the hardest bit,” she said. “It’s the last 10 yards. It’s the communication part now that’s the hardest.”

It remains unknown, for example, how many people die from box jellyfish stings alone in the Philippines, she noted. The last known count was made in 1987 by an Australian researcher, Peter Fenner, who estimated the death toll at around 500 people, mostly children, each year.

Most jellyfish species cause only pain and discomfort. Only the Cubozoan class, or box jellyfish, can be fatal, owing to tentacles with tiny poison darts called cnidocytes, which inject the venom into the body upon contact and puncture the blood cells. The resulting hyperkalemia, or the high level of potassium in the blood, causes the heart to stop.

Close encounter

Yanagihara also got into jellyfish research because of a close encounter with the deadly creatures in 1987. Then, fresh with a Ph.D., Yanagihara was taking a break on her stretch of Hawaiian beach when an old woman warned her of the “tiny glistening blobs” in the water.

“I thought it really couldn’t be that bad,” she recalled. “But when I was swimming back in, hundreds of them were being washed out through the coral break with the tide and I intersected with them.”

The pain, she said, could only be described as a kind of “burning,” a torment caused by countless “shocking needles” piercing her throat and arms.

She managed to get back to shore and into an ambulance and emerged from the experience, convinced that she had found the subject of a lifelong study.

Her research eventually helped her develop two products, now patented under the brand name Sting No More: a spray to remove clinging jellyfish tentacles and a cream to inhibit the spread of the venom. The products are currently sold in the United States, and she has donated a batch to her contacts in the Philippines.

PH ‘hot spots’

Box jellyfish are highly concentrated in the Philippines, where she has visited several times to collect specimens and personally check the situation in what she considered emerging “jellyfish sting hot spots,” hoping to empower these local communities.

Based on her fieldwork, Yanagihara sees potential hot spots in Quezon and Palawan provinces in Luzon; Tacloban City, Leyte, and Marabut, Samar, in the Visayas; and General Santos City in Mindanao.

With the help of local universities and community volunteers, she has gone around these areas to teach local disaster and health officials the best ways to respond to jellyfish sting cases.

The goal is to have an integrated approach—from understanding the local ecology of the hazardous area for better mitigation and prevention measures to educating the locals and correcting misconceptions.

Yanagihara once gave a talk on how a sting victim can be saved through CPR or cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Two months later, a local nurse who had listened to her was able to apply the technique and revive a young boy.

Proposed ordinance

In Lucena, Yanagihara had approached the city council to propose an ordinance that would require the documentation of jellyfish sting cases.

“When there is a mandate, then it would become a priority and we can finally get some light shed on the magnitude of the problem,” she said.

But for this effort to make any lasting change, Yanagihara is making the case for treating jellyfish stings as a public health concern in the Philippines. This means creating a network from the communities to the World Health Organization.

From there, it could later be treated as a regional problem since jellyfish-related deaths are also happening in Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand, she added.

‘Invisible’ danger

“In Australia or in Thailand, for example, because they depend on resorts, there are lots of proactive prevention and education” initiatives about jellyfish stings, she said.

There are huge warning signs about jellyfish colonies and beach wardens are taught first aid, she said, citing immediately doable measures.

“When the hot spots are [also] deep in poverty, like in the Philippines, there’s not much done … and I understand that [jellyfish stings] rank low in the whole health burden of the Philippines and why it has fallen through the cracks and is almost invisible,” she said.

But when this “invisible” danger claims the lives of children, Yanagihara said, the burden is immeasurable.

“That being said, if there is some way we can prevent deaths and improve the safety and happiness of coastal communities, then why not?”