Johnny Otis of ‘Willie and the Hand Jive’ inspired a Filipino jazz artist

SAN FRANCISCO—Johnny Otis, singer, songwriter, band leader, died Tuesday in southern California.

He was a legend, known as the godfather of rhythm and blues.

Many of you would familiar with his songs. I know Filipinos of my generation loved one of them -— though many of us probably didn’t know he wrote it.

Remember “Willie and the Hand Jive?” That was the song in one of the big dance numbers in the movie “Grease” starring the young John Travolta and Olivia Newton John.

That was a Johnny Otis song.

Article continues after this advertisementOne thing I also didn’t know until recently was the role the man who wrote “Hand Jive” played in the Filipino story.

Article continues after this advertisementJohnny Otis helped jump start the career of Sugar Pie DeSanto, the legendary Afro-Filipino blues singer from the Bay Area.

He also inspired Filipino jazz artist Carlos Zialcita. Not just Carlos’s music — but, more importantly, his passion for his culture, his past, his identity as a Filipino.

Sounds odd.

But, you see, Carlos, who moved to San Francisco as a child in the 1950s, built a thriving career as a jazz artist. But for many years, his being Filipino was just a minor element in his life and career — an insignificant detail.

Johnny Otis changed that.

They were similar in many ways. Johnny was the son of Greek immigrants. Carlos grew up in Manila and spent much time in southern Leyte.

He was 10 when he moved to San Francisco.

Like Johnny Otis, who grew up in Berkeley, Carlos eventually identified with African Americans and African American culture.

For Carlos, that was the result of being exposed to the black community in San Francisco, especially to their music. His family didn’t like him hanging out with African Americans. After all, Filipino immigrants back then were supposed to identify more with white society.

But Carlos ignored them.

In a funny twist, his grandmother unknowingly helped feed his growing interest in jazz and blues. She made Carlos say the rosary with her every afternoon by tuning in to a local radio station that led the daily prayer.

The station was actually also a black blues station.

“I’d turn on the radio and there was James Brown,” Carlos recalled. “And I said, ‘My god, I like this music. I kept getting pulled by black music, and black culture. I always had black friends.”

Playing jazz and blues became his career — his life. Carlos became a master of the harmonica, and played with the most famous artists of the 60s and 70s in cities across the country.

“Here I was doing the complete opposite of what my family wanted me to do,” he told me.

Eventually, his music career led him to Johnny Otis.

Johnny’s wife Phyllis is Afro-Filipino, a connection that inspired him to explore Filipino culture and the Filipino story in America.

One day, around ten years ago, Carlos recalled, “Something dramatic happened.”

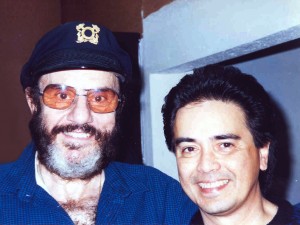

By then, he had become Johnny’s newest protege. And that day, his mentor showed him a copy of a book called, “Forgotten Asian Americans,” a classic account of the Filipino American experience by Fred Cordova.

“Son, this story needs to be told,” Johnny told Carlos.

“I had such deep respect for him that I had to listen to what he was saying,” Carlos said. But he also said: “I took four more years for that to sink in.”

That’s because for a long time being Filipino wasn’t really a big deal for Carlos.

He performed at Filipino events. But when his Filipino hosts asked him to talk about the connections between his Filipino-ness and his music, he didn’t how to answer.

“I’d get interviewed and I didn’t know what to say.” He just didn’t think much about his Filipino self — but now, he was constantly being asked these questions.

This was in the 1990s when young Filipino Americans, many of them children of immigrants who arrived before and after World War II were asserting their community’s story through the arts and culture.

This was when college students began holding annual festivals called Pilipino Cultural Night. Filipino cultural groups and theater companies emerged in major US cities.

Carlos, then in his 40s, found himself in the middle of a cultural awakening. Johnny Otis helped convince him to ride the wave, to celebrate his Filipino-ness.

Carlos found his voice, and a role he could play in telling the Filipino story.

“I sang Tagalog for the first time. I played ‘Dahil sa Iyo.’ I wanted everything Filipino.”

He helped start the Filipino American Jazz Festival in San Francisco, building on the success of a counterpart festival in Los Angeles.

In 2006, Carlos and other artists formed the jazz group “Little Brown Brother.”

My family and I watched him and his group perform at the La Pena cultural center in Berkeley during the holidays.

With Carlos on the harmonica, and his wife, Myrna Del Rio of Honduras on vocals, and other musicians — Ben Luis on bass, Chris Planas on guitar, Mio Flores on percussion, Rey Cristobal on piano, Carlton Care on drums and Ron Quesada on kulintang.

Yep, that’s right. They had a young Filipino playing kulintang at a jazz gig. Carlos called it jazz kulintang. One of the songs they played: “Fried Lumpia with Some Steamed Rice.”

Carlos calls what he went through a metamorphosis.

“It became the awakening of my Filipino consciousness. I went from being black to being what I already was — which was brown. It wasn’t a huge leap. It was a turning of a leaf.”

And Johnny Otis, the musician, impresario, activist, helped him find his way.

Which was why hearing of Johnny’s death was tough for Carlos. “I was crying uncontrollably at different points of the day,” he told me.

“The enormity of it hit me — the enormity of contribution to me as a person and to everyone. What an enormous gift he had given me with his friendship.”

“Johnny became a major force in my life.”

On Twitter @KuwentoPimentel. On Facebook at www.facebook.com/benjamin.pimentel