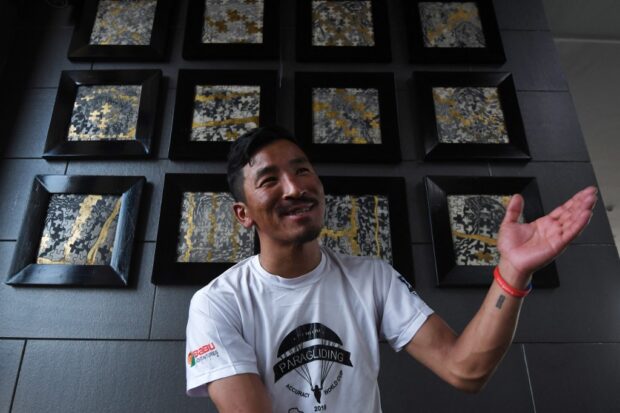

In this picture taken on June 2, 2023, Nepali guide Gelje Sherpa speaks during an interview with AFP in Kathmandu. Gelje abandoned his client’s Everest summit bid to rescue a Malaysian climber in a deadly season that has seen at least twelve deaths. (Photo by Prakash MATHEMA / AFP)

Kathmandu, Nepal — Ten years ago, Nepali mountain guide Dawa Tashi Sherpa was fighting for his life after being hit by an avalanche on Everest which was then the deadliest disaster on the world’s highest mountain.

The accident, which killed 16 Nepali guides on April 18, 2014, shone a spotlight on the huge dangers they face to let high-paying foreign clients reach their dreams.

READ: Nepali sherpa with record Everest summits behind him says he’ll keep climbing

Without their critical work to carve out climbing routes, fix ropes, repair ladders and carry heavy gear up the mountain, few foreign visitors could make it to the daunting peak’s top.

A decade ago, a wall of snow barrelled through the Nepali guides as they heaved heavy kit up the treacherous high-altitude Khumbu icefall in the freezing dark.

The force of the avalanche tossed Dawa Tashi about 10 metres (33 feet) down, injuring his rib cage, left shoulder blade and nose.

Dawa Tashi, then aged 22, recalled his friends who died. Three of their bodies were never recovered.

“I was lucky to survive,” he told AFP. “In the hospital, whenever I tried to sleep, they would appear in front of my eyes.”

The disaster led to protests for improved benefits and conditions for the guides, and an unprecedented shutdown on the peak for a season.

‘Tipping point’

It sparked a debate about compensation for the families of injured or killed Nepali guides and mountain workers.

Many are forced to rely on the charity of Western climbers — despite being employed by expedition companies and being fundamental to the multimillion-dollar industry’s success.

READ: From highs to lows, Everest record breaker sees ‘no future’ in Nepal

“It was very difficult back then,” said Nima Doma Sherpa, who lost her husband Tsering Onchu, 33, in the avalanche.

“What can you do when the main pillar of your house is not there? The children were small, and I was worried how I will educate them and how we will sustain ourselves.”

The government reaps hefty revenues from the lucrative climbing industry — in the last season in 2023, it earned more than $5 million from Everest fees alone.

Soon after the 2014 accident, it pledged a meagre $400 to the families of those killed to cover funeral expenses.

The offer was rejected by angry Nepalis, whose families received only $10,000 then in life insurance.

The resulting furious dispute, with Nepalis clamouring for better death and injury benefits from the government, saw days of tension at the base camp.

Sherpa guides, grief-stricken over the deaths of their colleagues, threatened to boycott climbing, throwing mountaineers’ plans into disarray and cancelling the season.

“It was a tipping point for young Sherpas who were frustrated,” said Sumit Joshi of expedition operator Himalayan Ascent, who lost three guides from his team in the avalanche that year.

Since then, his Everest teams have not climbed on the anniversary date.

“Ten years on, there is an improvement in their working conditions and the respect that they command,” he said.

Safety standards needed

In 2014, the protesters at Everest base camp made several demands.

They included an improvement in insurance payouts and a relief fund from mountain royalties.

“We were advocating for the Nepali climbers, ensuring they can get as much benefit as possible,” said Ang Tshering Sherpa who headed the Nepal Mountaineering Association at the time.

“But not all demands could be met as there were limitations.”

The insurance payout was increased by 50 percent to 1.5 million Nepali rupees ($11,250) if someone is killed.

Helicopters are now allowed to fly in supplies to higher camps, decreasing the number of trips Nepalis make across the treacherous Khumbu icefall.

Nepali companies have displaced foreign operators to bring in the majority of climbers, and pay and conditions have improved for guides at larger firms.

But, guide Mingma G Sherpa said, little else has changed.

“They protested, but it was limited to the base camp,” he said. “The main thing is that the government policies are still not good… we really need to set a standard for climbers to make the mountains safer”.

‘Wives don’t agree’

In 2015, a powerful earthquake triggered an avalanche that killed 18 people at Everest’s base camp before the climbing season began.

Last year’s season started with the death of three Nepali climbers carrying expedition supplies, after they were hit by glacial ice fall and swept into a crevasse.

Mingma G Sherpa said many local guides have quit the industry.

“The number of Sherpas has gone down significantly. Now companies have to go look for Sherpas. In the past, Sherpas would have to go around looking for work,” he said.

“We want to go to climb because we know the environment there, but the family members don’t want to send. The mothers and wives don’t agree.”

Survivor Dawa Tashi, who began trekking when he was just 11, still guides climbers and returned to Everest in 2021.

He is preparing to guide six Americans up the 6,461-metre-tall central Mera peak.

“There were improvements after the disaster, but it is not enough,” he said, pointing to the $11,000 fee each foreigner pays to the government to climb Everest.

“The government… should make a fund to safeguard the manpower,” he said.

“The clients would also happily pay it, knowing that it will be used to take care of their team.”