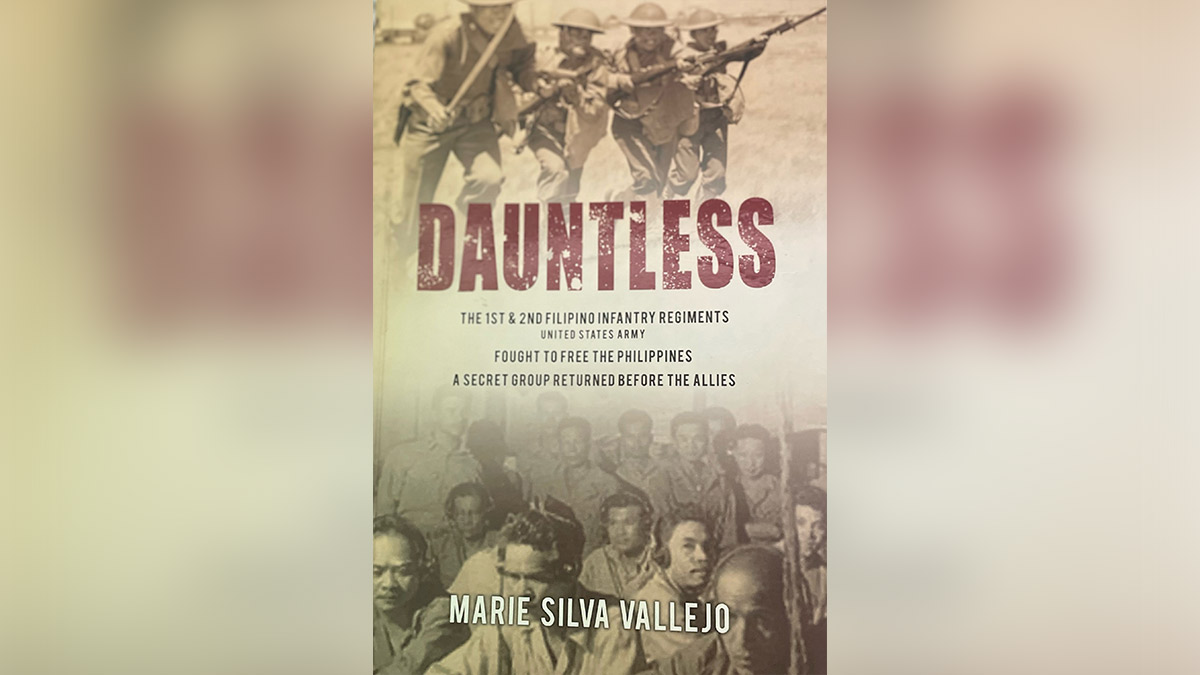

UNSUNG HEROES The cover of “Dauntless” shows images of some members of the 1st and 2nd Filipino Infantry Regiments of the US Army, the “unsung heroes” who helped liberate the Philippines from the Japanese.

CITY OF SAN FERNANDO — Two historians reckon that the way Filipinos understand World War II (WWII) as it happened in the Philippines is surely bound to change. They viewed the 761-page book “Dauntless” as a new lens to see it.

Marie Silva Vallejo, the author, brought to the fore the contributions of the 1st and 2nd Filipino Infantry Regiments of the US Army in helping free the homeland they left but still cared about.

Vallejo tried to fill in these gaps in the war narrative: After 63,000 Filipino soldiers and 12,000 American troops in Bataan province surrendered to the Japanese on April 9, 1942, and holdovers in Corregidor at the mouth of Manila Bay yielded the following month on May 6, “there is no information on what happened until the Americans returned two and a half years later [in Leyte in October 1944].”

READ: Children’s book tells stories of Filipina fighters in WWII

Not entirely true

“Even the young ones today think that the Americans returned to liberate us. But [it is] not entirely true. In those years in between, the guerrillas continued to resist with the help of the secret submarine missions that began arriving six months after the surrender,” Vallejo told the Inquirer in a recent interview.

She added: “They (guerrillas) brought supplies and sent intelligence on the enemy to Australia for [Gen. Douglas] MacArthur to plan a successful return that would save Filipino and American lives.”

Kept a secret for decades, the missions executed by US-based Filipinos were only unraveled in 1985, thanks to reporting by US veteran Alfredo Despy and research by Alex Fabros Jr., the son of a “manong” who enlisted. “Manong” refers to an Ilocano farmworker.

Vallejo also found herself connected to the regiments through an officer, her own father, Lt. Col. Saturnino Silva. It was after his death that she learned about his story or his unit’s bravery.

“The research and writing affected me so much in the last 10 years that I added a chapter—‘My Journey’—at the end as my story,” she related.

“The book is the story of these missions that worked with guerrillas to maintain the guerrillas’ and people’s morale, or we would have turned to the side of the Japanese. No one knew of these men until now,” Vallejo said.

In book-signing events, she writes: “They were heroes.”

‘Definitive’

Professor Ricardo Jose, a historian, has considered Vallejo’s book an “extremely important contribution to the understanding of WWII in the Philippines.”

“This is the first—and definitive—book-length history of Filipino-Americans and their units in the US Army and their contribution to the victory in their homeland,” Jose wrote in the blurb, adding it is “full of little-known details and connections, with so much appearing in print for the first time.”

Peter Parsons, another historian whose father Charles headed several missions, said that in telling the stories of the regiments, Vallejo “covers the whole of WWII in the islands, its many facets, and in amazing details.”

“Dauntless,” Parsons added, is a “monument in and of itself.”

Filipinos who have come to the United States since 1906 have reported experiencing rampant anti-Filipino sentiments and laws. The 1920 census showed them to be at 5,000. Yet, many signed up for the military after Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941.

Silva was drafted four months before the bombings. He sailed for the United States in 1929, using his savings from his salary as a teacher in Tawi-Tawi for two years.

“What complicated patriotism had made my father and thousands of Filipino men in America volunteer into the Army despite decades of horrible inequities inflicted upon them?” she wondered.

President Franklin Roosevelt formed the First Filipino Battalion in February 1942, with about 7,000 men joining. Its two regiments branched out into the First Reconnaissance Battalion (Special) and the 978th Signal Service Company.

Military records showed these units to be highly trained and known only to MacArthur and a few of his staff.

Bataan falls

Filipino and American forces that did not surrender to the Imperial Japanese Army turned to guerrilla warfare, gathering the support of civilians by raiding enemy camps and freeing villages.

The Allied Intelligence Bureau understood that “accurate information on the guerrilla resistance was needed, and intelligence on the Japanese from the interior part of the islands was important in the planning of MacArthur’s successful return to the Philippines.” The country was considered a strategic part of the Pacific campaign.

Filipinos in the service in the United States were transferred to the battalion, which was activated on April 8, 1942, in California. The manong from Ilocos in Luzon and working in the central valley of California made up a “large and significant group.”

The first regiment swelled to over 5,000 officers and enlisted men, with the second activated on Nov. 22, 1942. By Feb. 20, 1943, at least 1,200 soldiers were naturalized citizens with the motto of “fighting under the American flag to protect the Philippines from the Japanese.”By May 1943, a total of 87 officers, including Silva, were chosen from over 800 men to do advanced training in Australia. A batch of 400 men and 30 officers was selected, undergoing separate radio training schedules before reaching Australia.

Absolute secrecy was ordered for PRS (Philippine Regional Section) activities. The entire operation was labeled “Top Secret,” and all related memos were stamped as such.

The missions, men, the training camps in Australia and everything related to them were to be wrapped in strict security.

“These missions were devoted exclusively to coordinating the scores of scattered bands of guerrillas and supplying them with field radios and a systematic basis for collecting intelligence,” Vallejo wrote, citing a report.

According to her, the regiments were regarded as “advance echelon” in MacArthur’s campaign of liberation, being also called the “eyes and ears” of the general.

“The men were not to go into combat but to set up radio networks and gather intelligence on enemy dispositions to be used in the planning of the return. The personal arms and ammunition of the men were for defending the radio stations,” she said.

The initial decision was to land in Sarangani Bay in Mindanao and do a strong offensive on Leyte and Samar in December. The landing date was changed to October 1944 in Leyte, increasing the “pressure to produce qualified men at a faster rate.”

“Much of the location and activities of the Japanese forces were already known and destroyed by the guerrillas before landing. By the time our forces hit the beaches at Leyte, we had 134 radio stations—46 on Mindanao, 23 on Panay, 21 on Luzon, 13 in Negros, 11 on Leyte, six on Mindoro, five on Palawan, three each on Cebu and Samar, and one each on Bohol, Masbate and Tawi-Tawi,” an officer reported.

Vallejo said the “successful liberation of the Philippine Islands was significantly affected by the secret submarine missions of the 1st Reconnaissance Battalion (Special) for over two years until the Leyte and Luzon landings. They worked with the guerrillas to be the “eyes and ears” of the general headquarters [of the Southwest Pacific Area].

From January 1943 to January 1945, the Philippine Regional Section sent 20 submarines for 41 missions that delivered 1,627 tons of men, radio, weapons, supplies and propaganda, with the return trips evacuating 500 people. More than 14,000 radio messages were sent to the KAZ (King Able Zebra), MacArthur’s radio, in Australia. INQ