COMPOSITE IMAGE: JEROME CRISTOBAL FROM INQ/STOCK/PAMALAKAYA FILE PHOTOS

(First of two parts)

MANILA, Philippines—China is building a maritime ‘Great Wall’ in the South China Sea, including the West Philippine Sea, according to analysts who have been keeping tabs on Chinese aggression in the disputed waters.

But unlike the engineering marvel Great Wall built mainly for defense, the one that China is building on seas far from its coast is also for dominance, the analysts said.

In the 1990s, China started building structures over coral reefs and islets inside the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the West Philippine Sea. This was met by so far the strongest protest from the Philippine government—an arbitration case over the Scarborough Shoal standoff in 2012.

But China, instead, “flexed more of its military muscle.” The intrusion continued with impunity.

The Philippine government won the case filed at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 2016, which ruled that the Philippines has exclusive sovereign rights over the West Philippine Sea and that China’s nine-dash line assertion was at best fictitious and has no legal basis.

Despite this, China’s aggression persisted. Former Philippine ruler Rodrigo Duterte, pressed to enforce the arbitration ruling, described it as just a piece of paper he can throw into the waste basket, echoing comments made by the Chinese government.

READ: Why do China, Duterte descriptions of arbitral ruling look the same?

As the think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) said, China even shifted its focus toward asserting control over peacetime activity across the South China Sea, including the West Philippine Sea.

It said “a key component of this shift has been the expansion of China’s maritime militia—a force of vessels ostensibly engaged in commercial fishing but which in fact operate alongside Chinese law enforcement and military to achieve political objectives in disputed waters.”

Just last March, as seen in photos provided to INQUIRER.net by a professional civilian photographer, over 20 Chinese vessels, which are believed to be militias, were massing in Whitsun Reef, also called Julian Felipe Reef.

Chinese vessels, believed to be part of China’s maritime militia, massing in Whitsun Reef. CONTRIBUTED PHOTOS

The source was on board a small plane flying at above 5,000 feet when he took the photos of the swarm of vessels, a fully developed Chinese island fortress, the Pagasa Island, and a Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) vessel patrolling the waters off the reef.

Last year, the Philippines protested the presence of over 100 Chinese militia vessels in the same area. Back in 2021, over 220 boats, also believed to be part of China’s maritime militia, were seen massing in Whitsun Reef, too.

READ: Chinese militia vessels in WPS show Beijing’s endless blatant disregard of PH EEZ

Dr. Francis Domingo, a De La Salle University (DLSU) assistant professor specializing in international relations and strategy and war, said “the use of maritime militia is part of gray zone tactics” by China.

He told INQUIRER.net via Telegram INQUIRER.net on Tuesday that gray zone tactics, which have been part of China’s strategy, are “tactics that are beyond diplomatic activities but are short of armed conflict.”

“China is demonstrating that it can advance its national interests without triggering an armed conflict or use of military force,” said Domingo. “It wants all the options available at its disposal.”

At a forum organized by the think tank Stratbase ADR Institute, analysts said this strategy, which included the deployment of CCG vessels and maritime militias, enabled China to build island fortresses in the disputed waters without starting a war.

READ: PH to China: Stop harassment in West Philippine Sea

Lawyer Jay Batongbacal, director of the University of the Philippines’ (UP) Institute for Maritime Affairs and the Law of the Sea, explained at the forum that in the West Philippine Sea, “we see these gray zone operations occurring on [a] daily basis.”

“They have at least two dimensions,” he was quoted as saying by the Philippine News Agency.

One of them, Batongbacal said, is “visible seaborne operations,” which could include the activities of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) in the background, the CCG asserting China’s massive claim over the South China Sea, and the deployment of maritime militia vessels.

The other dimension, he said, are “narratives of powerlessness meaning that they are somehow persuaded that they cannot do anything about these competitive actions by the other state”—the narrative that Chinese seaborne operations are intended to convey.

Dr. Elaine Tolentino, an international relations analyst and a DLSU associate professor, said “from the perspective of other claimant states, most of them, including the Philippines, simply do not have the maritime capability to thwart these boats.”

Then “from the perspective of regional powers who do have the naval capacity to deal with them, including the United States, [they] will not engage with these fishing vessels directly as it would only further escalate the issue,” Tolentino told INQUIRER.net by FB Messenger.

READ: Deeper defense ties with US: What it means for PH

So “these Chinese militia vessels (supported by Chinese law enforcement) play a highly significant part in achieving China’s strategy of contesting other Southeast Asian claimants without provoking an outright conflict at a minimum cost to the government,” she said.

As pointed out by Professor Dindo Manhit, president of Stratbase ADR Institute, the West Philippine Sea “has long been a ground for gray zone tactics whose ambiguity and threatening features undermine the established rules-based international order.”

Is China prepared for war?

During his presidency, Duterte repeatedly balked at actively asserting Philippine sovereignty over WPS, saying the Philippines cannot possibly win a war with China, a statement of resignation that was roundly condemned and disputed by critics of his pivot-to-China policy.

Dr. Chester Cabalza, president and founder of the think tank International Development and Security Cooperation, told INQUIRER.net by FB Messenger that “China is highly prepared on the ground since its massive military modernization was conceived by Chinese paramount leaders.”

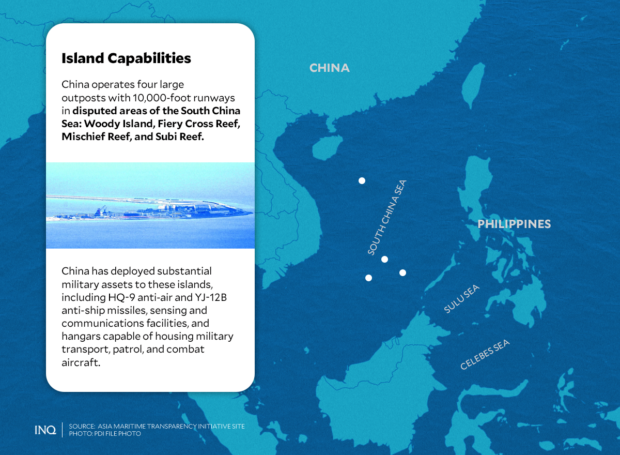

The Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI), which keeps track of developments in the South China Sea, said China’s deployment of radar, anti-ship and anti-air missile platforms, and combat aircraft to its outposts in the South China Sea has greatly expanded its ability to project power in waters far from its own coast.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan based on Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan based on Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan based on Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan based on Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan based on Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan based on Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan based on Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

It said in a 2021 article that China “operates four large outposts with 10,000-foot runways in disputed areas of the South China Sea: Woody Island, Fiery Cross Reef, Mischief Reef, and Subi Reef.”

“China has deployed substantial military assets to these islands, including HQ-9 anti-air and YJ-12B anti-ship missiles, sensing and communications facilities, and hangars capable of housing military transport, patrol, and combat aircraft,” AMTI said.

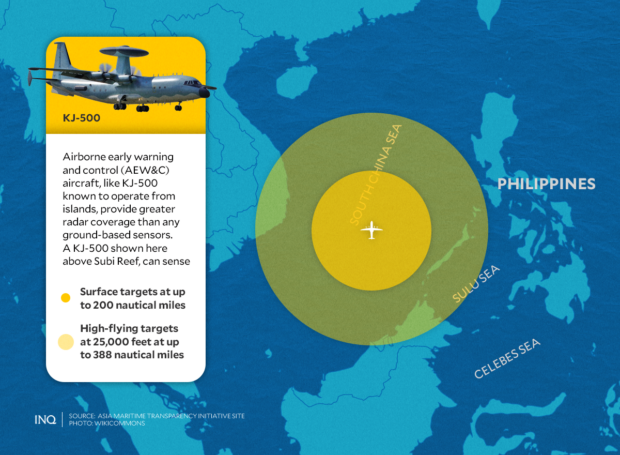

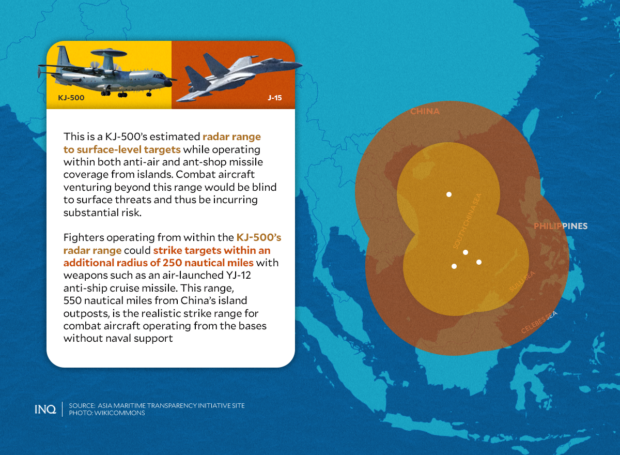

However, AMTI said “combat aircraft can only effectively operate within the range of available radar and sensing platforms” since “without external radar coverage, they have limited awareness of their surroundings.”

RELATED STORY: AFP tells China to restrain forces in the West Philippine Sea

So there is an airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) aircraft, like the KJ-500, which provides greater radar coverage as it can sense surface targets at up to 200 nautical miles and high-flying targets at 25,000 feet at up to 388 nautical miles.

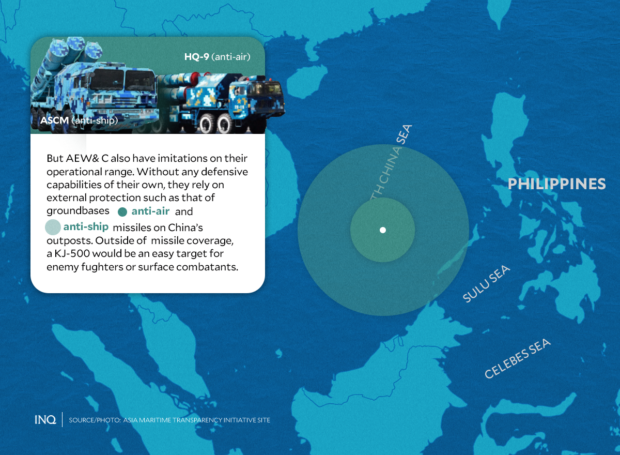

But AEW&C aircraft also have limitations on their operational range: “Without any defensive capabilities of their own, they rely on external protection, such as that of ground-based anti-air and anti-ship missiles on China’s outposts,” said AMTI.

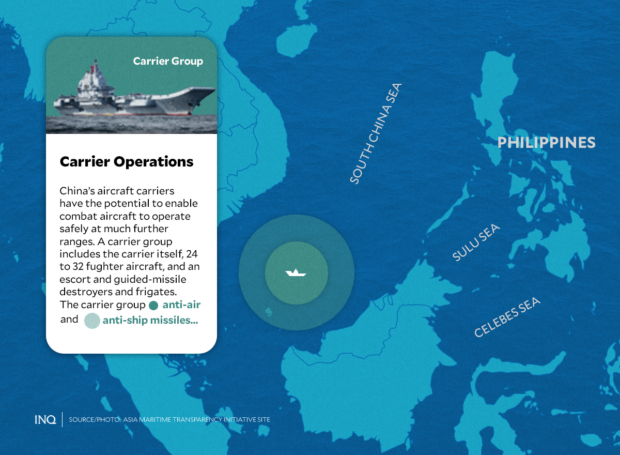

Likewise, AMTI said China’s aircraft carriers have the potential to enable combat aircraft to operate safely. A carrier group includes the carrier itself, 24 to 32 fighter aircraft, and an escort of guided-missile destroyers and frigates.

The carrier group has its own anti-air and anti-ship missiles, as well as radar that can detect surface and air targets, but its radar range to surface targets is limited to approximately 65 nautical miles.

“This limits the strike range of combat aircraft launched from the carrier, which, without other support, can only safely operate within that radius,” AMTI said in its article “Air, Land, and Sea: China’s Maritime Power Projection Network.”

Cabalza told INQUIRER.net that the militarization of reclaimed islands in the West Philippine Sea are “strategic and made in preparation for possible naval skirmishes.”

“It is seen as a Great Wall at sea despite China’s lack of naval warfare and world war experience. Apparently, it is a naval fortress for prepositional military advantages,” he said.

Consistent with what the AMTI presented, Domingo said that in the event of an attack and China’s deployment of military forces in the South China Sea, assets of PLAN are also capable of waging war.

RELATED STORY: Salt on open wound: More fish imports for PH as China blocks Filipino fishers

But Cabalza said “the militia boats are highly trained for intelligence-gathering, known as carriages for logistics, small ammunitions and materiel, including personnel trained for tactical operations.”

Cabalza, a UP professor and security expert, said that “the synchronicity of attacks are exercised daily by these militia boats as personnel are trained for unrestricted or irregular warfare.”

The CSIS explained that maritime militia vessels fall into two main categories — professional militia vessels and commercial fishing vessels recruited into militia activity by subsidy programs and known as Spratly Backbone Fishing Vessels (SBFV).

“Professional vessels are generally built to more rigorous specifications that include explicitly military features, although even SBFVs are steel-hulled and measure at least 35 meters, with many measuring 55 meters or more,” said CSIS.

It said the vessels participate in large deployments aimed at asserting Chinese sovereignty, and both deny access to foreign countries’ ships, but statements from officials suggest that more aggressive operations would first be entrusted to professional vessels.

According to an article on China’s maritime militia and fishing fleets, which was published by the Army University Press in 2021, the maritime militia is a separate organization from both the PLAN and CCG.

The militia, it said, consists of citizens working in the marine economy, “who receive training from the PLA and CCG to perform tasks including but not limited to border patrol, surveillance and reconnaissance, maritime transportation, search and rescue, and auxiliary tasks in support of naval operations in wartime.”

While the authors, Shuxian Luo and Jonathan Panter, presented the weaknesses of the militia vessels being small in size, they stressed that Chinese fishing vessels’ “weaknesses,” however, do provide some asymmetric advantages.

First, they said because they are cheap, fishing vessels will always outnumber warships: Deployed in high numbers using swarm tactics, small craft can pose an asymmetric threat to warships, as US Navy experience with Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy forces had shown.

READ: Tensions in West Philippine Sea not ‘cooling down’ – Marcos

But their slow speed lessens their ability to maneuver and increases the period of exposure to layered defense, although the vessels’ civilian masks could reduce the risk that they will be fired upon.

“Instead of a kinetic threat, Chinese fishing vessels present more of a disruptive one. Deployed in even limited numbers, fishing boats can inhibit, if not prohibit altogether, a warship’s ability to conduct towed array and flight operations (both essential for anti-submarine warfare, a critical capability given China’s growing anti-access/area denial forces in the South China Sea),” the article said.

RELATED STORY: PCG: Fewer Chinese vessels in WPS but warship remains

Second, they said fishing vessels pose a huge identification problem.

“As small craft, they generate minimal radar return even in clear weather and mild sea states. In addition, Chinese fishing vessels frequently do not broadcast their position in Automatic Identification System and use only commercial radar and communications technology, making them hard to identify by their electronic emissions,” the article said.

“For these reasons, in combat operations, the maritime militia’s primary role would likely be reconnaissance support, although some vessels have also received training in minelaying,” it said.

RELATED STORY: Del Rosario: Marcos ‘taking proper steps in defending’ West PH Sea

TSB