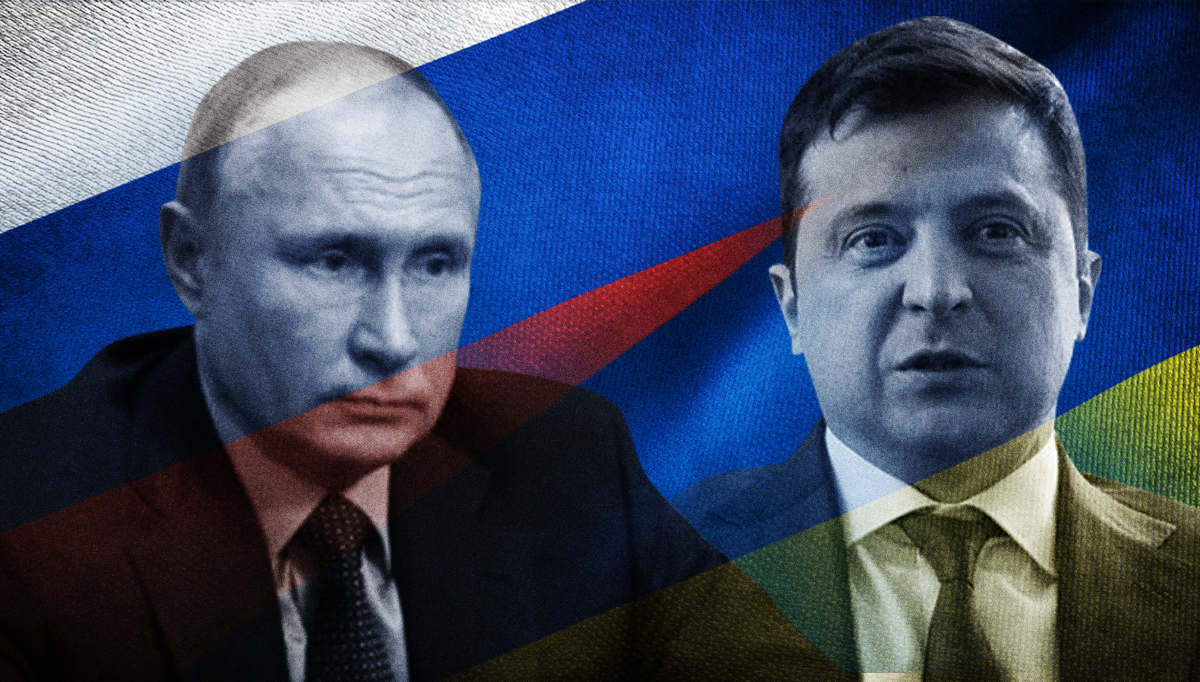

FILE PHOTO

MANILA, Philippines—As war broke out in Ukraine and sanctions were imposed on Russia, overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) found themselves hit––directly or indirectly––by the conflict.

On Feb. 24 when Russian dictator Vladimir Putin launched his war on Ukraine, announcing that he had ordered a “special military operation” on Russia’s neighbor and unleashing bombs on civilian communities.

READ: Russia’s Putin launches invasion of Ukraine

Five days after the launch of his war, Putin said Russia’s nuclear deterrent forces should be on a “special regime of combat readiness.” This, as he accused the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), an organization of democratic countries, of “aggressive” remarks while imposing financial sanctions.

Since the invasion of Ukraine, the United Nations (UN) Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights said 474 civilians had been killed while 861 were wounded––out of these, 17 among the dead and 30 among the wounded are children.

The UN said the lives of millions of civilians in Ukraine continues to worsen, especially now that the International Committee of the Red Cross stressed that people are already drying out of essentials.

This, as the war strikes as a “catastrophe” for the world economy, said David Malpass, president of the World Bank, in a BBC interview.

The Central Bank of Russia said while the ruble, Russia’s currency, would continue to trade, the Russian stock market was likely to remain closed.

For international affairs analyst Rasti Delizo, war always brings down the gross domestic products (GDP) of international markets, saying that GDP in all regions of the world will likewise be hit.

RELATED STORY: Why it matters: How Putin’s invasion of Ukraine could impact PH

He said since war triggers a rise in oil costs, Europe may have to source energy from elsewhere, which will mean higher prices. This will also slow down economic stability.

“We will definitely see global supply chains being disrupted all over the world. The world trade will be disrupted,” Delizo, who is also a socialist activist, told INQUIRER.net.

While the consequences of the war become clear now––financial sanctions, rising costs of basic commodities and supply-chain disruptions––how are OFWs directly or indirectly hit?

The Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) said there are over 300 Filipinos in Ukraine while Anakalusugan Rep. Mike Defensor said there are over 10,000 Filipinos in Russia, citing DFA data.

Leaving the war

Last Feb. 23, Foreign Affairs Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr. said the Philippines’ “chief concern” is the safety of OFWs in Ukraine, saying that they will be taken out of harm’s way and sent to safety the fastest possible way.

Foreign Affairs Undersecretary Sarah Lou Arriola said on Tuesday (March 8) that the DFA had already extended help to 199 Filipinos in Ukraine. Last Monday (March 7), a Filipino mother and her child had returned to the Philippines from Ukraine.

The DFA said 63 Filipinos had already been repatriated to the Philippines, six were evacuated to Poland, 33 were evacuated to Moldova, 73 were evacuated to Romania, nine were evacuated to Austria, while 15 were evacuated to Hungary.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The DFA issued Alert Level 4 for Ukraine, the highest crisis alert level which is issued “when there is large-scale internal conflict or full-blown external attack.” The DFA ordered “mandatory evacuation.”

RELATED STORY: Over 300 Filipinos in Ukraine urged to evacuate

“Filipinos in Ukraine will be assisted by the Philippine Embassy in Poland and the Rapid Response Team, which are presently assisting Filipino nationals for repatriation and relocation,” the DFA said.

Arriola told ANC last March 4 that 116 Filipinos were still in Ukraine while 200 seafarers were stranded. She also said two cargo ships with Filipino crewmen have already been hit by a bomb or a missile believed launched by Russia.

READ: 116 Filipinos still in Ukraine, around 200 seafarers ‘stranded’ – DFA

Financial concerns

Unlike what Filipinos are seeing in Ukraine, OFWs in Russia said they were safe and that they are still working. However, they were directly or indirectly hit by the financial sanctions imposed on Russia.

With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the European Union, Japan, United Kingdom, the United States , Canada, New Zealand, and Taiwan already imposed sanctions against Russia.

Sergey Aleksashenko, former deputy finance minister of Russia, said in an Al Jazeera column that the “most powerful blow” to the Russian financial system are the sanctions imposed on the Central Bank of Russia.

He said it plays a critical role in the domestic foreign exchange market, stressing that it has an immense foreign exchange reserves of $640 billion “and it traditionally regulates the level of the ruble exchange rate.”

Last March 7, $1 is worth ₽155. Before the Russia and Ukraine conflict, $1 was worth ₽70 to ₽80. With this, ₽1 already lost 90 percent of its value against $1 since the start of 2022.

With this economic downslide, Delizo said a typical family in Europe may have to let go of OFWs “because that’s the immediate battle area.” “Many will think of coming back home, however, many will stay,” Delizo said.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Citing data from the DFA, Defensor said in a statement that at least 95 percent of OFWs in Russia, mainly in Moscow, are household service workers, cleaners, cooks and drivers earning at least P20,589 per month, the minimum wage set in Russia.

Rising costs

TIME magazine said that the drop in ruble’s value will likely send inflation rising. Emem Esguerra, a Filipino hairstylist in Moscow, Russia, told INQUIRER.net that Filipinos in the Russian city are already feeling the impact.

For instance, a child’s milk that is worth ₽1,100 is now ₽1,600. Ana Valdez, a household service worker, said Filipinos are already feeling the rise in the cost of commodities, saying that some goods are even 20 percent higher.

“We are hit by the financial sanctions imposed on Russia because now, the cost of commodities are already rising,” Valdez, who is working in Moscow, told INQUIRER.net.

Phoebe Zoe Sanchez, a history and sociology professor of the University of the Philippines Cebu, told INQUIRER.net that when there is war, the cost of commodities rise because “traders capitalize on the situation.”

“They will capitalize on the problem of supply when there is war so there’s a tendency that even transportation or mobility will be difficult. That’s the implication. Filipinos will find it really hard,” she said.

Sanchez, who is a visiting professor of the Université Catholique de Louvain in Belgium and the spokesperson for BAYAN-Europe, said when there is war, “we see the intersection of personal and social problems.”

OFW remittances

The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) said the cash remittance of OFWs in Ukraine was P6.9 million in 2020 and P6.2 million in 2021 while OFWs in Russia were able to send P125.9 million in 2020 and P115.3 million in 2021.

However, as Filipinos in Ukraine were already being sent home and those in Russia are struggling to live with the consequences of the financial sanctions, the war is now expected to take its toll.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Esguerra said that before the war, ₽24,820.01 was already enough for his family to receive P16,000. As the conflict broke out, he said that he needs ₽38,834.95 for his family to receive P16,000.

Presently, ₽1 is worth P0.40. It was P0.68 on Feb. 16, more than a week before Putin initiated an attack on Ukraine last Feb. 24. Esguerra said P1 is now worth ₽2.43.

Filipinos in Russia are likewise experiencing some difficulties in sending remittance as banks, like the Central Bank of Russia, VTB, and Sverbank, faced sanctions.

READ: Filipinos in Russia face struggle in sending remittances as banks bear sanctions

Esguerra explained that OFWs in Russia are likewise hit by the sanctions which barred some Russian banks from the SWIFT international payments system. This, Al Jazeera said, could cripple Russia’s ability to trade with most of the world.

Migration expert Emmanuel Geslani told INQUIRER.net that when OFWs in Russia send remittances, they first need to have it changed to dollars, but as the ruble lost its value, “what will happen now?”

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Banks are significant for OFWs in Russia because they find it convenient. Valdez said that while Filipinos really need to have “rubles changed to dollars,” there are ways, through banks, like “PaySend,” to send remittances directly.

For Geslani, OFWs, especially those who already lost their jobs, “should keep their dollar savings and the best thing to do is to go home or go to the embassy because there is assistance there.”

Extend help to families

With the difficulties, that OFWs in Russia and Ukraine found themselves in, Defensor asked the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration on March 4 to extend financial assistance to families of OFWs in Russia

“The global sanctions are bound to hit Russia’s banking system very hard, possibly obstructing the money transfers of the more than 10,000 Filipino workers there,” he said.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Defensor stressed: “We are counting on the OWWA to reach out to the families here at home of our workers in Russia, and to provide them temporary financial relief.”

For Sanchez, the government should really help the OFWs and their families, especially now that most Filipinos overseas will not be able to send remittances.

There should be a provision for contingency funds whenever there is a crisis because most of the government taxes come from the incomes of Filipinos working overseas.

OFWs are helping the Philippines so it’s only right for the government to provide a regular program to respond to the needs of OFWs when there are crises and distress.

The BSP said personal remittances grew by 5.1 percent in 2021––$34.88 billion––and exceeded $33.19 billion in 2020. This contributed to the rise in domestic demand, with the 2021 level accounting for 8.9 percent and 8.5 percent of the GDP and gross national income.

Defensor said that “the prospect that some of our workers there might lose their jobs is very real, considering the projections that the Russian economy might plunge into a depression due to the global sanctions.”

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Esguerra told INQUIRER.net that some Filipinos in Russia, who are working for expats, have already lost their jobs since their employers, mostly Westerners, decided to leave Russia.

For Geslani, while these OFWs can still look for new employers through their networks, “if I were them, I would really just try to leave Russia because rubles no longer have value.”

Sanchez explained that the expats possibly left Russia because of these reasons—it was their personal decision or it was the recommendation of the embassy.

She said if it was because of the recommendation of the embassy, “there is something in the work of these people that is against the interest of Russia or the interest of the other parties.”

Work in PH

Delizo explained that OFWs, who decide to remain overseas, will find it difficult to either stay in their work or be forced to look for other jobs, which will also be constraining because the job markets for OFWs will shrink.

He said it’s clearly up to Filipinos if they will leave or not, but whatever is the case, he stressed that the Philippines should already adopt and pursue a national macroeconomic policy framework based on economic reforms.

These reforms, he said, should have longer terms to maintain employment in order to help Filipinos who are not employed and those who have work but don’t earn enough.

There should be reforms “to give enough living wage to be able to live not only a decent and dignified human life, but have excess for basic commodities.” He said there should likewise be work opportunities across all regions.

“Even if the OFWs in Russia come back by tonight, they land here, by tomorrow, they will be jobless. How will they sustain themselves and their families if the general economic environment of the country remains?” he said.

This was likewise stressed by Sanchez, saying that neoliberal policies are imposed in the Philippines and these are the problems that OFWs will encounter should they decide to return home.