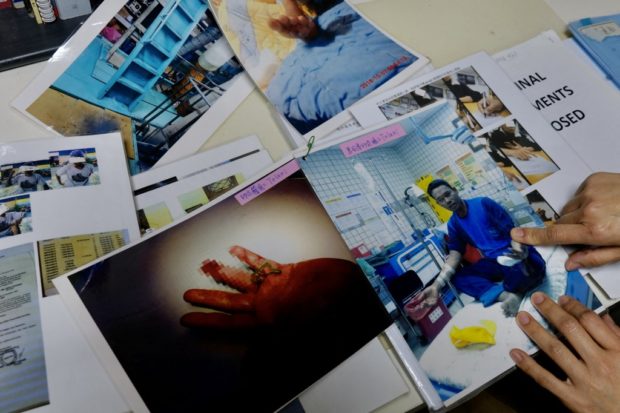

In this picture taken on December 4, 2020, Allison Lee, secretary general of the Ilan Migrant Fishermen Union (YMFU), points at a picture of missing Indonesian fisherman Tolani during an interview near Suao harbor in Ilan. Taiwan’s lucrative fishing industry has come under fire for subjecting its migrant workforce to forced labor and other abuses, contrasting with the government’s promotion of the democratic island as a regional human rights beacon. Photo by Sam Yeh / AFP

TAIPEI — Taiwan’s lucrative fishing industry has come under fire for subjecting its migrant workforce to forced labor and other abuses, contrasting with the government’s promotion of the democratic island as a regional human rights beacon.

Taiwan operates the second largest longline fishing fleet in the world with boats spending months — and sometimes years — crossing remote oceans to supply the seafood that ends up on our supermarket shelves.

But those who work on its vessels — mostly poor migrants from the Philippines, Indonesia and Vietnam — paint a grim picture of punishing work hours, docked pay, months without family contact, regular beatings, and even death at sea.

Last year the United States added fish caught by Taiwan’s deep water fleets to its list of goods produced by forced labor for the first time.

It was an embarrassing moment for Taiwan, an island that shook off autocracy and markets itself as one of the region’s most progressive democracies.

Recent steps include becoming the first place in Asia to legalize gay marriage, a historic apology by President Tsai Ing-wen to the island’s indigenous communities and an ongoing campaign to address abuses of the martial law era.

But there has been little headway in tackling labor abuses, especially within the $3 billion fishing sector.

Migrant fishermen interviewed by AFP said they routinely had to work up to 21 hours a day, enduring verbal and physical abuse as well as zero communication with the outside world.

When pay finally arrived, it was often lower than agencies promised.

Supri, who like many Indonesians uses just one name, said he was still traumatized by a stint on a Taiwanese fishing boat.

The captain, he said, took an instant dislike to him, scolding him frequently, locking him in a freezer and ordering a crew member to shock him with a stun gun used to kill fish.

“All the while I kept thinking I wanted to go home,” he told AFP. “I didn’t want to die. I wanted to see my family again.”

‘Modern day slavery’

In a survey of Indonesian fishermen published last year, the Environmental Justice Foundation found a quarter reported physical abuse on Taiwanese longline vessels, 82 percent worked excessive overtime hours and 92 percent had wages withheld.

Mohamad Romdoni, an EJF campaigner in Indonesia, said working conditions are “still terrifying” on Taiwanese boats — albeit marginally better than those on China’s fleet, the world’s largest.

“If the crew can still chew and swallow their food then they still have to work, even if they are sick,” he told AFP.

Edwin Dela Cruz, president of the non-profit International Seafarers Action Center in Manila, put it more starkly: “The labor conditions for fishermen on Taiwanese vessels is like modern day slavery.”

Filipino Marcial Gabutero came home from a long stint at sea to find his wife gone and his recruitment agency refusing to hand over four-fifths of his $250 monthly wage.

The 27-year-old said he was often beaten with a broomstick but never dared to speak up.

“We were helpless, so we endured until we finished the contract,” he said.

The Seafood Working Group, a coalition of NGOs that monitors abuses within global fishing fleets, estimates some 23,000 people work on Taiwan’s deep water vessels.

Earlier this year it recommended Taiwan be downgraded in Washington’s annual human trafficking report, citing wage deductions, forced labur, murder and the disappearance at sea of migrant fishers.

“Investigations have consistently revealed egregious human rights abuses in Taiwan’s fishing industry,” researchers wrote.

Flags of convenience

The worst practices are found on Taiwan’s deep water fleets which operate outside of the island’s waters and many use “flags of convenience”.

Those ships are owned by Taiwanese but flagged to countries with fewer regulations.

While deep water ships are expected to comply with Taiwanese hiring regulations there is no official inspection regime and no enforcement for those flying flags of convenience.

Taiwan’s Fisheries Agency said it “doesn’t allow forced labor or human trafficking” and was working to “amend relevant regulations in a timely manner”. The agency said it was planning to submit an “action plan” to the government, but could not give a date.

Last week the government’s own watchdog — known as the Control Yuan — said the fisheries department and other ministries had taken no concrete measures to address fishing abuses despite being aware of them.

Allison Lee, from the Yilan Migrant Fishermen Union, says officials have been reluctant to really solve abuses.

“The government is only sugarcoating and window-dressing the issue,” she told AFP.

Deaths at sea

Migrant workers have died on boats, often in suspicious circumstances.

One death that sparked an international outcry was Indonesian fisherman Supriyanto in 2015.

He was initially reported to have succumbed to an illness until harrowing personal testimony and video was smuggled out by his crewmates.

Lee, who has assisted Supriyanto’s family since his death, said the 47-year-old suffered frequent beatings at the hands of the Taiwanese captain who “hit his head with a fishing hook, cut his feet with a knife and encouraged others to smack him”.

No prosecutions have yet been made in that case.

A similar death occurred in 2019 when a 19-year-old Indonesian fishermen passed away a day after crewmates said he was struck by a Taiwanese officer.

“The captain wrapped up my dead friend’s body with a blanket and then stored him in the freezer,” an anonymous crew member said in testimony gathered by Greenpeace.

That vessel — the Da Wang — operates under a Vanuatu flag of convenience and the US has since placed it on a blacklist.

Last year it docked in Taiwan’s Kaohsiung city. Local prosecutors visited to inquire about the case but no departure ban was placed on the boat and it slipped back into international waters a month later.

Lee says cases like the Da Wang encapsulate the way Taiwan authorities are turning a blind eye to abuses.

“There are many problems with their treatment on board but there is no place for them to turn to for help,” she said.