SEATTLE — Ninety years ago during the Great Depression, the 17-year-old peasant Carlos Bulosan traveled from his small village in the Philippines and arrived in this city.

Bulosan would become one of the great writers of his generation and make a decisive impact in the struggle of Filipino migrant laborers in America.

But the anniversary of his arrival here came and went without fanfare last month, no thanks to the pandemic gripping the United States and the rest of the world.

To escape the virus stalking America, my family and I drove a thousand miles from Los Angeles, determined to mark the historic milestone by visiting Bulosan’s grave in Mount Pleasant Cemetery at Queen Anne Hill in this city, where the number of Covid-19 cases has abated.

Bulosan died in Seattle on Sept. 11, 1956. It was to be my first time in the city, in part to fulfill a promise I had made to Aurea Bulosan Gentile, the writer’s only surviving niece and guardian of his literary estate, that I would visit the grave of her famous uncle.

I met Aurea and her two daughters Laveta and Karen in LA in October 2017, when they were guests at our Carlos Bulosan Book Club of which I am a founding member.

Now 90 years old, Aurea lives in Huntington Beach, California.

‘America is in the Heart’

No other Filipino writer has had a huge impact on generations of Filipino-American readers as Bulosan. It can be argued that the history of Filipinos in America took a quantum leap with the publication in 1946 of his semi-autobiography, “America is in the Heart.”

Now required reading in most Asian-American study programs in the United States, the book was reprinted in May last year by Penguin Classics, making Bulosan the fourth Filipino writer to be so honored after Jose Rizal, Jose Garcia Villa and Nick Joaquin.

Bulosan’s literary canon has inspired writers across the ethnic spectrum from Jessica Hagedorn and Maxine Hong Kingston to Thanh Nguyen, the last Asian-American to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 2016.

I find it fitting that three Filipino-American writers across three generations—E. San Juan Jr., Jeffrey Arellano Cabusao and Elaine Castillo—wrote the prefaces to the Penguin edition.

Bulosan’s impact across generations is reflected in my own family. I first read “America is in the Heart” in 1984, as I worked to complete my degree in journalism at the University of Santo Tomas (UST). My sons Iggy and Neale would read the book three decades later as part of their literature classes in California.

The late poet Ophelia Alcantara Dimalanta, our literary criticism professor at UST, urged our graduating class of 1984 to embrace Bulosan’s writings and take part in the effort to rescue his literary legacy from oblivion.

As a journalist, I admired Bulosan’s almost messianic belief that he would become the voice of Filipinos in America and in his homeland.

As an immigrant, I also found solace and comfort in his words when I—in much the same way he did—struggled to hold down menial jobs when I first arrived in America in 1991 as a refugee.

Bulosan, his life and his work are still relatively unknown in the Philippines.

But his legacy is being revived in his hometown of Binalonan, Pangasinan, where a museum in his honor is being built, according to activist Cindy Domingo, one of the founders of the Bulosan Exhibit in Eastern Hotel at the International District in Seattle.

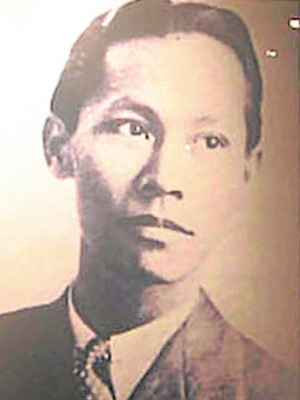

HIS LEGACY IS IN THEIR HEARTS The author at the grave of Carlos Bulosan, an immigrant who struggled to survive and faced racism in the United States before becoming one of the greatest Filipino writers of his generation. —CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

Landscape of desolation

Bulosan, a school dropout, disembarked at the port of Magnolia (now Pier 91) on steerage aboard the Dollar Line from Manila in July 1930, when the Philippines was still an American colony.

Far from the tech hub that it is today, Seattle was a muddy shantytown reeling from the economic collapse of 1929 that left people without jobs, without homes and without food.

It was this Seattle and its landscape of desolation that met Bulosan. He traveled the West Coast in search of jobs in farms and orchards and even made it to the canneries of Alaska.

The young man would soon encounter a racist America that brutalized poor immigrants and lowly migrant workers like himself. His frail body would soon be at the receiving end of cruel beatings from racist thugs and the police.

He found some solace in public libraries where, it is said, he spent hours reading books of all kinds. It seemed inevitable that he would become an activist and union organizer.

But Bulosan, traumatized by physical abuse and social injustice, was often in poor health. He taught himself to write prose and poetry while battling tuberculosis at the LA County Hospital in California and later at the Firland Sanatorium here.

His powerful words in defense of the working class have reverberated through time, inspiring such leaders as Larry Itliong and Philip Vera Cruz, whose activism is immortalized in a school now named after them in Union City, California.

If Bulosan were alive today—in the age of Facebook and Twitter — he would feel vindicated in his crusade against prejudice and injustice in a country undergoing a reckoning of its racist past.

If Bulosan were alive today and had a Twitter account, he would be trolling President Donald Trump who called Filipinos “animals” and “terrorists” on Aug. 4, 2016, in Portland, Maine, when first campaigning for the presidency.

If Bulosan were alive today, he would be fighting for Filipino nurses and doctors, who make up the bulk of the Filipino diaspora in America and who are dying at a staggering rate from Covid-19.

Bulosan’s only surviving relative in the US, Aurea Bulosan Gentile (second from right, seated), joins members of the book club named in her uncle’s honor in a 2017 meeting in Los Angeles. —CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

Green grass

When my family and I finally arrived at the cemetery where Bulosan is buried, I was overcome with emotion. At his grave, I knelt and felt the cold black granite with my febrile fingers.

The epitaph that Bulosan himself wrote while at the brink of death reads: “Here, here the tomb of Bulosan is. Here, here as his words, dry as the grass is.”

In this summer of the great pandemic, green grass grew over the grave of the great Carlos Bulosan. I hope his place in the pantheon of writers will be secure for many more summers. —CONTRIBUTED