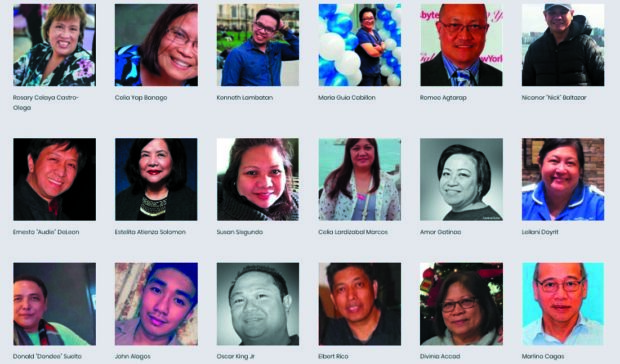

DIGITAL WALL Overseas Filipino health workers who died of COVID-19 are given due recognition at www.kanlungan.net, a project of transnational organization AF3IRM to recognize their sacrifices at the risk of their lives. —SCREENSHOT FROM KANLUNGAN WEBSITE

(First of two parts)

MANILA, Philippines — When the new coronavirus disease spread to the United States earlier this year, Rosary Castro-Olega did not think twice about coming out of retirement and working again as a nurse.

It was the kind of decision that would naturally come from the 63-year-old Filipino-American, said her eldest daughter, Tiffany Olega. Her mother retired in 2017 after 37 years of service at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California. But whenever help was needed in any hospital, she was always ready to lend a hand.

“She wore scrubs even when she’s on her days off,” Tiffany, who also lives in Los Angeles, said in an interview. “That was her life for almost 40 years of nursing, and she couldn’t get away from it.”

First to die in LA County

In mid-March, Castro-Olega started to have coughs and fever. On March 23, she was admitted to Panorama City Medical Center, where she later tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, the causative virus of COVID-19. She was intubated the following day. Tiffany was told that her mother would not make it past Friday, March 27.

On March 29, Castro-Olega died. She left behind a husband and three daughters, including twin girls who also fought the virus at the same time as their mother, and a twin sister who is also a nurse.

Castro-Olega was the first health worker to die of COVID-19 in Los Angeles County, home to nearly half a million Filipinos and Filipino-Americans.

As the pandemic accelerates, many more Filipino health workers are at risk of losing their lives in a battle where thousands of Filipinos and people of Philippine descent are placed front and center.

Despite this grim reality, many of them remain unnamed and unrecognized for their sacrifices.

This is what the “Kanlungan” project, through its digital memorial for fallen workers, hopes to remedy.

Brainchild

Kanlungan, a Filipino word meaning “refuge” or “shelter,” is an online memorial wall that pays tribute to people with Philippine ancestry who comprise a huge part of the global health-care system that is under pressure from the coronavirus.

The brainchild of feminist organization AF3IRM, the project also aims to fill the gap in the data on Filipino health workers who have been among the first casualties of the pandemic.

Castro-Olega is the first entry in the memorial, being the aunt of Jollene Levid, AF3IRM’s founding chair. Levid has lost another aunt to COVID-19 and her family remains under threat from the virus, as most of them are medical workers.

“How are we supposed to demand better protective equipment for health-care workers, hazard pay, and everything that they need if nobody is even counting our dead, or let alone, naming them?” Levid said in an interview with the Inquirer.

Kanlungan (www.kanlungan.net) serves to remember the fallen health workers as “human beings, not simply as a labor percentage, a disease statistic or an immigration number.”

With the coronavirus lockdowns in many countries, Filipinos who have lost loved ones in the pandemic have found it difficult to properly mourn. The digital gallery, however, offers some semblance of solace that the sacrifices of their parents, spouses and children are not forgotten.

As of press time, more than 160 health workers are honored in the digital gallery. A data map shows that the majority of the fallen lived and worked in the United States, numbering at least 78. The next largest group lived in the United Kingdom, where at least 44 Filipino medical workers have died. A vast majority of those who have died are women.

The memorial has received more than 5,000 visits since its launch in May. Family members of those who died have also begun reaching out to AF3IRM to have their relatives included in the memorial.

World’s largest nurse supplier

Filipinos have been serving in the medical profession around the world for decades. The Philippines has become the world’s largest supplier of nurses, exporting so many it now finds itself short of them as it battles the new coronavirus.

In the United States, the history of Filipino nurses dates back to the end of the Spanish-American war, said Catherine Ceniza Choy, author of “Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History.”

As a US-occupied territory, the Philippines was home to hundreds of nursing schools that adopted the trends of American professional nursing. Through a series of policies, such as the Exchange Visitor Program of 1948 and the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, waves upon waves of Filipino families traveled across the Pacific to the United States.

“In the early 1970s, the Marcos government began to actively promote the export of Filipino nurses and other Filipino laborers abroad,” Choy wrote. “Filipino nurses working abroad would become the new national heroes through their remittance of desperately needed foreign currency to the Philippines.”

At present, there are nearly 130,000 Filipino nurses in the United States. In the United Kingdom, nearly 18,500 Filipinos work in the National Health Service, the third-largest group after Britons and Indians. Thousands more have been exported to the Gulf states, such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia.

AF3IRM’s Levid, whose mother was recruited as a nurse from Manila to Missouri, said many immigrant health workers were also exploited, ending up in jobs that other people do not want.

“We are filling the gaps with the export labor policies of the Philippines,” she said.

Despite the significance of Filipino health workers, Levid said structural racism in the United States had prevented recognition of their crucial role in the American health-care industry.

She expressed hope that through Kanlungan, immigrant and migrant Filipinos would be given due recognition.

Tiffany Olega finds comfort in knowing that her mother had cared for other people and saved their lives.

“I hope she will be remembered as more than a mother to three daughters,” she said. “She was a mother to everyone.”

(To be concluded)