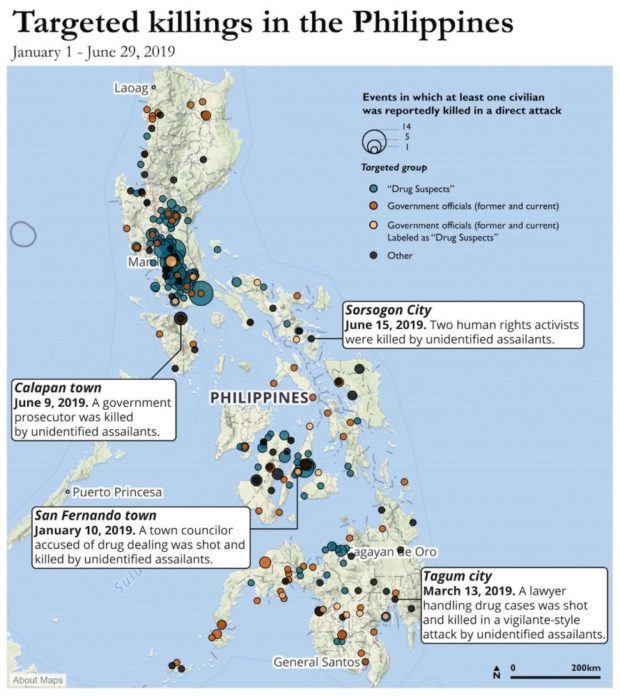

Map of targeted killings in the Philippines based on data and analysis by Acled. PHOTO FROM ACLED WEBSITE

MANILA, Philippines – A United States-based research group stood by its 2019 report that found “damning” data that showed increased violent attacks on civilians in the Philippines that exceeded those in countries being torn apart by full-scale war.

Sam Jones, communications manager of data analysis group Armed Conflict and Location Project (Acled), said in an e-mail to Inquirer.net that the Philippine National Police (PNP) and Malacanang reaction to the group’s 2019 findings was expected as the group’s 2018 report on attacks on civilians worldwide, including in the Philippines, got a similar reaction from Philippine authorities.

Jones, however, said “data don’t support” a statement made by lawyer Salvador Panelo, spokesperson and chief legal counsel of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, claiming that the Philippines was, indeed, a dangerous country but only for criminals and the corrupt and not innocent civilians.

In its report, Acled said 450 direct attacks on civilians had claimed the lives of at least 490 people since the start of 2019 in the Philippines. The numbers placed the Philippines fourth on a list of countries deemed dangerous for civilians because of “targeted attacks” or attacks aimed directly at those who had been killed and not just unavoidable results of so-called collateral damage.

The list showed only three other countries—India, Syria and Yemen—having more civilian casualties because of targeted attacks. Syria and Yemen are in the middle of civil war.

PNP Chief Oscar Albayalde on Monday (July 15) raised doubt on the credibility of the Acled report saying its findings were belied by other international studies, like an HSBC 2019 survey of expatriates where the Philippines was 24th most preferred expat destination on a list of 33 countries. Vietnam was 10th on that list.

HSBC’s 2019 Expat Explorer Survey had 18,059 expats around the world as respondents. A minimum sample of 100 expat respondents and at least 30 expat parents were required for a country to be included in what HSBC said were league tables.

Expats were asked to rate a country by quality of life, physical and mental wellbeing, fulfilment, cultural, welcoming and open communities, political stability, ease of settling in, income, disposable income, economic stability, career progression, reaching potential, work and life balance and expat children’s prospects of making friends, learning and schooling.

Albayalde pointed to that survey as proof there’s no truth to the Acled data.

“I think that is unfounded,” Albayalde said of the Acled report. “That cannot be covered by data. I don’t know how they were able to say that,” he said.

“What’s their basis for saying that?” the PNP chief added.

He said Acled may have based its report on data from local sources who want to bring the government down. It was “very unfortunate,” he added, that some Filipinos would pass on false information about the Philippines to international groups.

If Acled’s report was true, “the country would then be full of chaos, which is not the case,” Albayalde said.

“That’s why we challenge these people to come here and live here and see for themselves how peaceful the Philippines is,” the PNP chief added. International investigators or fact-finding missions, however, had been declared unwelcome by Palace officials

In a paper explaining its methodology in data collection about killings in the Philippines, Acled said it considered the drug-related violence in the country as “political violence’.

“This type of violence manifests in a number of ways,” the Acled paper said. It said violence related to drugs in the Philippines was included in counting attacks on civilians and covered the killing of drug suspects “by both government security forces and by vigilantes as well as inter-gang related violence.”

Acled acknowledged that the veracity of some of the reports was suspect and that’s why the group exerted effort to “accurately capture the patterns and trends of violence in the Philippines.”

Dr. Roudabeh Kishi, Acled research director, said in an earlier e-mail to Inquirer.net that “information from various sources is aggregated by researchers on a weekly basis, meticulously coded and goes through three rounds of review before data are published.”

Kishi said the numbers that showed up in Acled research and analysis of civilian targetting in the Philippines were “damning.”

Sam Jones, the Acled communications chief, said it seemed to him that Albayalde and the presidential spokesperon, Panelo, had contradicted each other in reacting to the Acled report. While Albayalde declared the entire report untrue, Panelo, though maybe in an attempt to be sarcastic, had admitted that the Philippines was, indeed, a dangerous place but not for innocent civilians but criminals and the corrupt.

“Because law enforcers would not stop against criminals and drug lords, pushers who are destroying the fabric of our society,” Panelo said at a Palace briefing on Monday (July 15). “It’s really dangerous in the Philippines so if you’re a criminal and you come here, or if you’re a syndicate member, it’s really dangerous here,” Panelo said.

Jones said Acled “simply found” that the Philippines “has the fourth-highest number of targeted attacks on civilians across the regions we cover so far in 2019.”

“The fact that we record a higher number of direct attacks on civilians in the Philippines than in countries experiencing active warfare, like Afghanistan or Somalia, is evidence of extreme levels of targeted anti-civilian violence,” Jones said in his e-mail to Inquirer.net.

Albayalde protested the emphasis on killings when the Duterte administration’s campaign against drugs has also resulted in 240,565 arrests between June 2016 to May 2019.

The PNP chief was likely to frown over another report, this time by an office under the US State Department, which said kidnapping is a “persistent problem” in the Philippines.

The 2019 report, posted on the website of the Overseas Security Advisory Council (OSAC), said that in 2017 and 2018, all foreign victims of kidnapping in the Philippines have been Asians. No Westerner had fallen victim to kidnapping during those years, the report said.

It blamed the payment of ransom, common in kidnappings in Mindanao, for the continued occurrence of such crimes.

“Success in securing ransoms worth millions of dollars may have further incentivized KFR activities,” said the OSAC report using the initials for kidnapping-for-ransom.

“In southern Mindanao, KFR injects significant amounts of money into the local economy which could suggest tacit support by the local populace,” said the report by the OSAC, an agency under the US State Department’s Bureau of Diplomatic Security.

Although foreign, mostly Asian, nationals had been targeted, the report cited the Philippine National Police Anti Kidnapping Group (AKG) as also reporting that victims of kidnapping between 2017 and 2018 were “predominantly Philippine citizens.”

Kidnappings involving Filipino victims, the report said and still citing the AKG, are mostly perpetrated by Muslim extremist groups.

While blaming kidnappings on what the report said were insurgents, it also said that “majority of cases appear to be criminal and not ideological.”

“The perpetrators appear to target local business people and individuals perceived as affluent,” the OSAC report said.

Aside from the threat of kidnapping, the OSAC report also said the US State Department has “assessed Manila as being a HIGH-threat location for crime directed at or affecting US government interests.”

“Crime remains a significant concern in urban areas throughout the Philippines,” the OSAC report said.

The US State Department, the report added, has also classified Manila as a high threat location for terrorist activity.

“For the last several years, the Department of State has warned US citizens of the risks of terrorist activity in the Philippines,” the report said.

“Terrorist groups and criminal gangs continue to operate throughout the Philippines,” it said.

Although saying that the threat of kidnapping is persistent in the Philippines, the OSAC report also cited “host nation media” as saying that the number of kidnapping cases had declined.

It cited the AKG as listing 43 cases of kidnappings in 2017 with mostly Filipinos as victims and 14 of the cases happening in Mindanao.

The report came amid international concern over the uncanny style of President Rodrigo Duterte in fighting criminality, mainly drug trafficking, which his top officials said had been effective in bringing peace and order.

The Philippine government had acknowledged more than 6,000 deaths in Duterte’s brutal campaign against narcotics which he had repeatedly blamed for a host of other crimes like rape, killings and robberies. /ac