‘Despairing of the future’

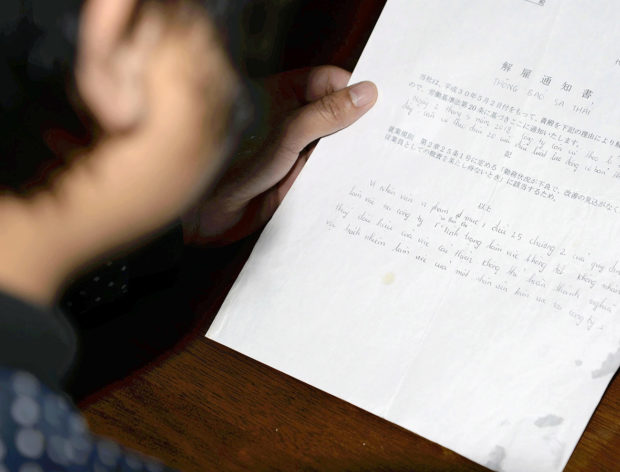

“I cannot repay my debt. All I can do is to shut myself behind closed doors with my head in my hands,” a 28-year-old Vietnamese man said while placing his head on a desk at a private house in Koriyama, Fukushima Prefecture, that provides protection for foreign technical intern trainees.

The house is run by a civil group that supports foreign technical intern trainees who disappeared from their workplaces. Four foreigners including the Vietnamese man were living in the house at the time of the interview.

The man came to Japan in July 2017 and began working as a technical intern trainee at a company that makes and sells concrete products in Toyama Prefecture.

The organization in his home country that arranged his internship asked him to pay a ¥1.05 million (about $9,500) fee in the name of an intermediary, and he borrowed the full amount from a bank. Since a contract agreement he signed before coming to Japan states that his monthly salary would be ¥150,000 (about $1,360), the man had planned to repay the debt within two years.

However, after deductions for his dormitory fee, insurance premiums and other costs, his take-home pay was only about ¥80,000 a month, so he could hardly repay the debt or send money to his family.

At his workplace, he also suffered violence. In May 2018, employees of the company asked him to submit his passport, saying, “Your work attitude is terrible. Return home.” Thinking that he would be forced to go home, the man fled to Koriyama to seek protection from the civil group, which he learned about via Facebook.

After disappearing, he was dismissed by the company. His dream of learning civil engineering technology in Japan and working at a civil engineering and construction company in Vietnam has been displaced by lament: “It’s difficult to repay the debt in my home country. I’m too ashamed to face my parents. I despair of the future.”

Difficulties repaying debt

According to a Justice Ministry survey on 2,870 technical intern trainees who went missing from their workplaces, 2,381 of them — more than 80 percent — paid more than ¥500,000 to the dispatching organizations in their home countries, and 2,552 — nearly 90 percent — came to Japan in debt.

A Chinese woman who worked as a technical intern trainee at a farmer’s house in Ibaraki Prefecture had paid about ¥720,000 to an intermediary when she came to Japan in 2013.

A Nepalese woman who came to Japan in 2011 worked at a farm in Okinawa Prefecture, paying about ¥700,000 to a dispatching organization. However, due to difficulty repaying her debt, she went missing.

On Dec. 25, the government adopted basic and operational policies, as well as a comprehensive package of relevant measures.

The basic policy stipulates that the government will take thorough measures to eliminate malicious brokers. As a concrete measure toward that purpose, the government will oblige foreign nationals to write the names of brokers on the application documents they submit upon entry to Japan.

Although the measure is aimed at sussing out shady brokers that collect expensive commissions, the government has yet to decide whether to ask foreigners to provide documents that prove the involvement of the brokers, such as detailed statements about the money. False statements would be difficult to detect.

“Measures against brokers are a never-ending issue. This deserves criticism for lacking in specifics,” an immigration control authority source said.

When it comes to the existing Technical Intern Training Program, brokers also in Japan have come to the surface.

In August 2018, immigration control authorities uncovered a 27-year-old Cambodian man who allegedly promoted illegal labor in violation of the Immigrant Control and Refugee Recognition Law. He had been arranging illegal work for technical intern trainees via Facebook and demanded that each of them pay ¥250,000 in return for living arrangements and other things.

In principle, when the involvement of a malicious broker comes to light, companies accepting relevant trainees are expected to be banned from accepting foreign technical intern trainees for five years. However, there are no legal definitions of malicious brokers or specific measures to detect their involvement.

Eriko Suzuki, a professor of labor sociology at Kokushikan University who is familiar with labor issues involving foreign workers, said: “Measures against brokers stipulated in the comprehensive package of measures lack details or specifics. It cannot be helped that intermediary agents are involved in matching employers and workers under the new program and completing various procedures for the entry of foreigners into Japan. It’s impossible to eliminate shady brokers only through the efforts of the private sector.

“Learning lessons from the Technical Intern Training Program, the government should establish a new system under which a public organization should take charge of matching and other issues,” Suzuki added.