Bharat Vatwani: I think we have been lucky in the sense that the job satisfaction, the emotional feeling of joy, has been terrific from day one, and that has sustained us over the years. —JOAN BONDOC

Bharat Vatwani and his wife, both psychiatrists, were snacking at a restaurant in Mumbai, India, one noonday in the late 1980s when a long-haired scrawny man staggering across the road caught their eye.

Using an empty coconut shell, the man scooped up filthy water from a canal and drank it “like a single shot,” Vatwani said.

The couple realized that he was mentally ill. Driven by a shared emotional spark, they offered him free treatment at their private nursing home.

In two months, the man’s condition improved enough for him to be reunited with his father, who traveled 1,000 kilometers from their village to get him, Vatwani told the Inquirer in an interview on Wednesday.

‘This kind of work’

Vatwani said he and his wife realized that nobody was engaged in “this kind of work” for people “whose entire existence is kind of wiped out.”

That was the prelude to the establishment in 1988 of Vatwani’s Shraddha Rehabilitation Foundation, which nurses the mentally ill found wandering in the streets of India and reunites them with their families.

Over three decades, more than 7,000 people who’ve suffered various mental ailments, such as schizophrenia, dementia and bipolar disorder, have been treated at the lush 2.6-hectare rehabilitation facility in Mumbai’s countryside.

Shraddha, the Sanskrit word for “faith,” can accommodate 120 patients and is a far cry from the ordinary mental health care institutions that often look and feel like a prison. It has wide open spaces where patients could farm or grow vegetables.

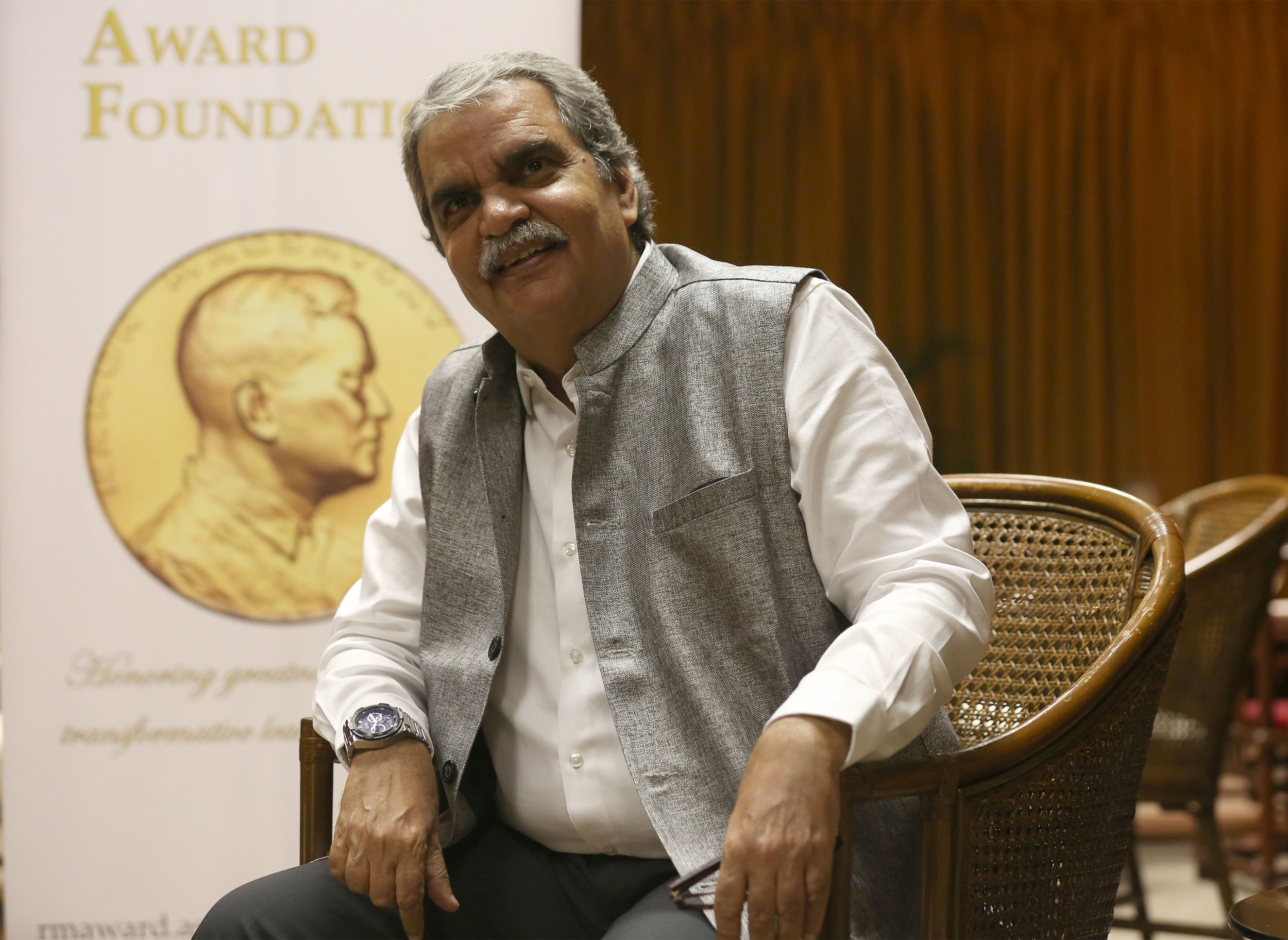

For his work, Vatwani, 60, will receive this year’s Ramon Magsaysay Award, Asia’s highest honor. He was cited for “embracing India’s mentally afflicted destitute” and “affirming the human dignity of even the most ostracized.”

Vatwani said he views the award “as a testament to the plight of the wandering mentally ill.”

A difficult life

His lifelong work has been a battle to pull the wandering mentally ill from the peripheries into the spotlight of Indian society where they are shunned and neglected.

Vatwani said he himself had a difficult life, making it easy for him to empathize with the “down and out.”

His father died when he was 12 years old, forcing him to do odd jobs—like peddling Agatha Christie novels and photographs of movie stars—to make money to continue his studies.

Vatwani put himself through medical school but saw himself a “misfit in medicine.” But a visit to a psychiatric ward where he “identified immediately” with the patients made him decide to be a psychiatrist.

In trying to change the state of mental health care in India, Vatwani battled not just widespread stigma against the mentally ill but also the pervasive centuries-old tradition of supernatural healing and “black magic.”

This is why returning patients to their loved ones is more than just orchestrating grand family reunions, he said. The patients became ambassadors for mental health care in their villages, many in remote rural areas, simply by showing that medication, not voodoo, works.

“[It] creates a flutter in the entire village,” Vatwani said. “Not only has the patient come back, but he’s come back in a much better shape, so that means there is treatment somewhere.”

Reuniting with families

The role of reuniting patients with their families often falls on the shoulders of Shraddha’s social workers, who are so thorough that they could put private investigators to shame.

Patients are paired with social workers who speak the same dialect. Like detectives, the social workers, who come from all over India, get personal details from the patients that would lead them to their families, including names, schools, rail lines that pass through their villages, even regional movies they’ve seen.

Vatwani recalled one patient who came home to his family just hours after his grief-stricken mother had died and was about to be cremated. In India, that is considered a “miraculous time,” because when a child performs the last rites before cremation “the soul of that person [who died] will go into heaven,” he said.

Finding patients is much easier than looking for their families, Vatwani said.

He said they used to pick patients off the streets with their own ambulances. But after word about his foundation had spread, policemen, social workers and private groups from all over India make referrals.

When patients arrive, they are in very bad condition—often anemic, plagued by infections, beaten up and neglected—but they leave Shraddha as castaways-turned-conquerors, he said.

Despite his achievements and multiple awards, Vatwani feels he needs to do more. He belongs to a rare breed of Indian doctors who have chosen to continue their practice at home. He notes that there are more Indian psychiatrists in the United Kingdom than in India.

“I think we have been lucky in the sense that the job satisfaction, the emotional feeling of joy, has been terrific from day one, and that has sustained us over the years,” he said.