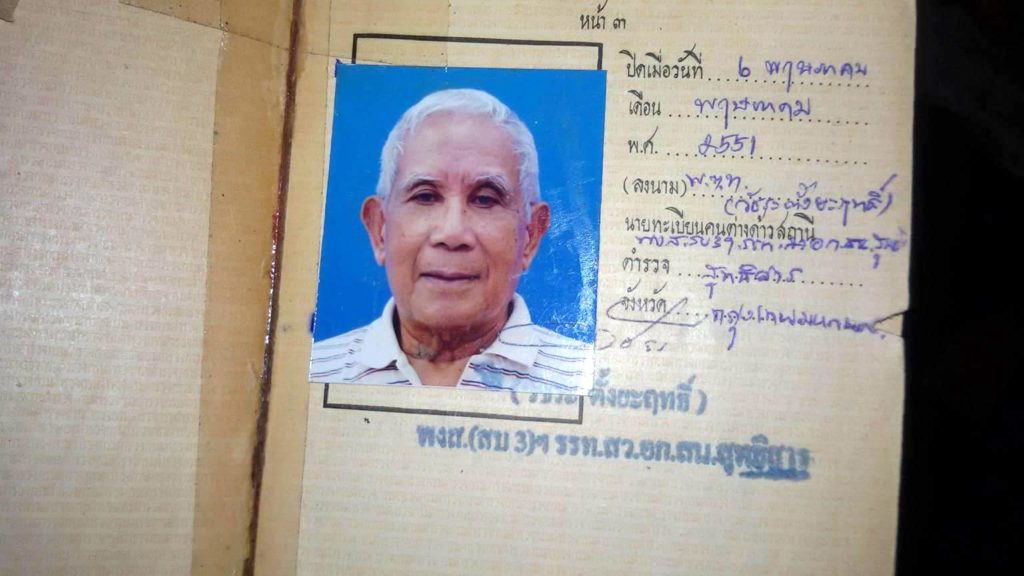

Lolo Ernesto De Jesus San Juan’s pass book. CONTRIBUTED

Winning Tower is a 22-storey building with 487 units located at Pridi Banomyong and Sukhumvit Road, Phrakhanong, Bangkok. Completed in 1994, it is a popular residence for Filipino workers due to its accessibility to airport link and sky trains.

Ernesto De Jesus San Juan, a 95-year-old Filipino of Gapan, Nueva Ecija, has been staying there, at 958/423b Sukhumvit Rd., Soi 71, since 2008 as his document says. But it was only on March 1, that his Filipino neighbors knew his name and his desire to go home for good. He started knocking on doors, asking for food. His mental faculties are fading.

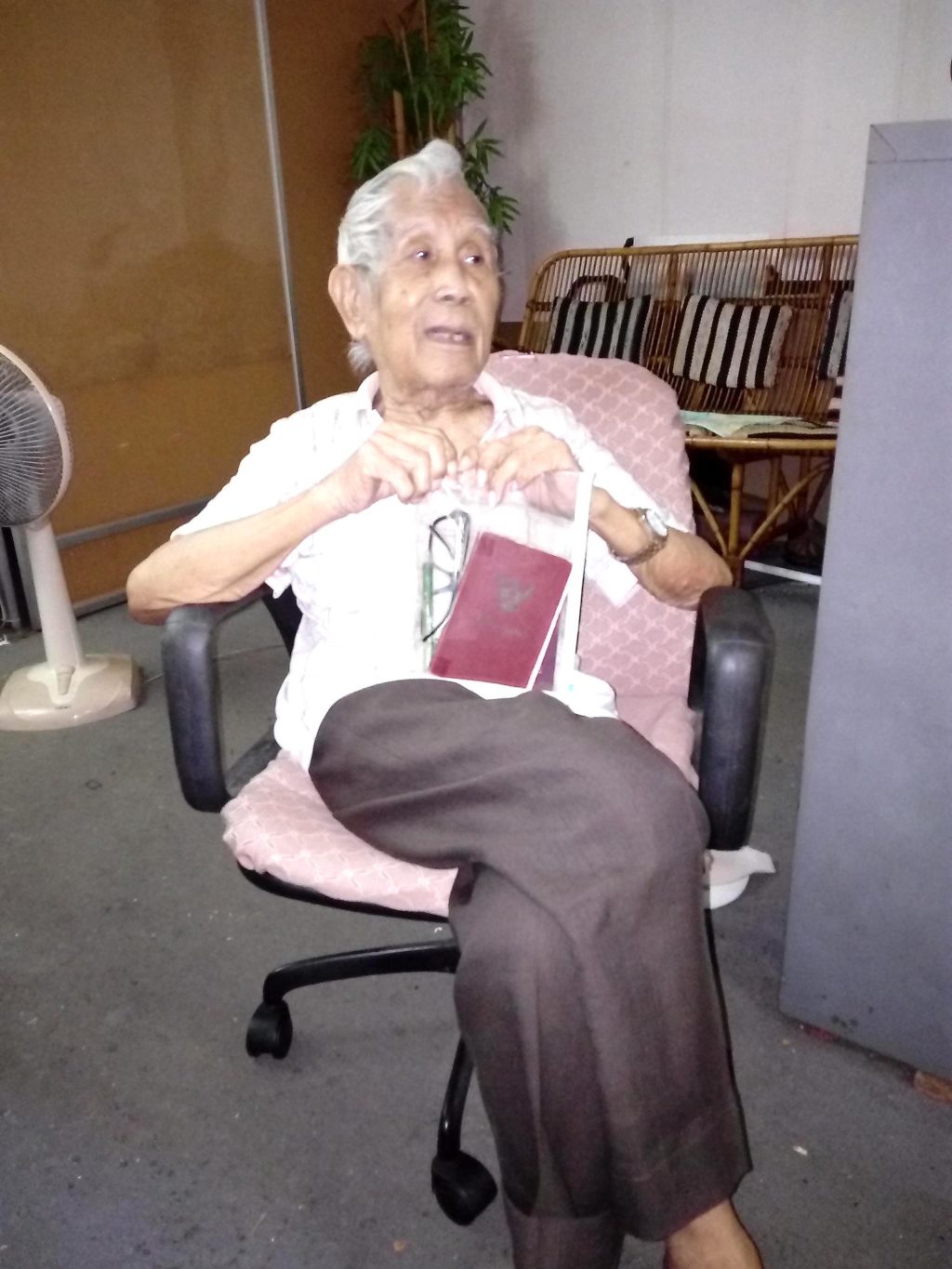

A video of Lolo Ernesto was posted on the Facebook page “Kababayan at Kapamilya sa Thailand (KKT)” on March 1. In the video, Lolo Ernesto is seen talking about the Golden Triangle, and Pasig City. He doesn’t mention where in the Philippines he can go home to. He has no family and has been living alone for many years, the longest resident in the Tower said.

Jane Cabaya, the administrator of KKT and a leader in the Filipino community, sought my attention in the hope of understanding Lolo Ernesto.

I was surprised to see him as barely 5 feet tall, although age may have bent him. Lolo Ernesto immediately told me stories that happened long before all of us in the room were born, a story of the changing political landscapes of the Indochina region, and of gold in the Mekong region.

Golden Triangle is gold

Ernesto started his journey at Gapan, Nueva Ecija. “Bukana,” he said, was an entrance to the town he helped build as a young man. “Nueva Ecija is the entrance to Northern Luzon. That’s where I started. But I don’t know them anymore,” he said.

Lolo Ernesto De Jesus San Juan today. INQUIRER/Eunice Barbara C. Novio

After the WWII, he worked for Jacobo Zobel de Ayala, a Spanish Filipino industrialist and philanthropist. (Jacobo Zobel de Ayala was the only name he mentioned.)

“I was sought by many people for advice. I don’t know, I may be an expert,” he said.

The ability to speak four languages gave him an advantage in working with the locals in Laos. He was assigned to Pakse, Luang Prabang and Vientiane. He stayed in the country for more than 10 years but constantly moved within the countries that surrounded the Golden Triangle and also in Vietnam.

“Golden Triangle is not just opium. It is literally gold. But you got more money from opium,” Ernesto claimed.

He insisted that no one sent him there but his “friends.” He expressed his dismay in America and all other nations involved in the Golden Triangle. “They used the people, like the Hmong tribe, to gain wealth. I could have been wealthy today, but I would never meet you,” he smiled.

Who sent Ernesto to these missions? What are the organizations that operated in the turbulent region at the time?

MAAG Laos

Based on his Registration Booklet, Ernesto was sent to Laos in November 1958-1963. His employer was the Military Assistance Group (MAAG Laos). Highly decorated WWII veteran Reuben Tucker was one of MAAG Laos’ commanders.

MAAG became a key force during the anti-communist campaign in French Indochina during the ‘50s. President Harry Truman signed the National Security Council (NSC) Memorandum 64 in March 1950 proclaiming that Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos “could not be allowed to fall to the communists and that the United States would provide support against the communist aggression in the area.”

MAAG personnel reached to 685 personnel, all US citizens who had served during in WWII. They had an “advisory” role. They assisted in training local soldiers and facilitating military aid in the countries where they were sent.

In the account of William G. Bowles, a Special Forces US Army Sergeant sent to Laos, (the-wanderling.com/white_star.html), an operation called “Operation Hotfoot,” later called Operation White Star, was not clandestine. It trained and advised the Royal Laotian Army, which also included the Hmong and other hill tribes. It has began in 1959 and ended in 1962 as a result of the Geneva Accords that established Laotian neutrality.

“Late in 1958 and early 1959 our political and military leaders decided to put a highly trained military force into the Laotian Kingdom (Laos) with the mission to organize, train, and develop their military forces so they could control, suppress, and eliminate the growing communist forces in the country.”

Ernesto’s document says that he worked as a “trainer which is military in nature” in Pakse, Luang Prabang and Vientiane provinces of Laos. He mentioned the Hmong tribe as the one used by the Americans in fighting the “opium trade” and the communists.

Air America 108

Presumably, after MAAG, Ernesto worked job at Air America in December 1963. His job occupation was described as “teaching soldiers how to fly.” His job locations were Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand.

General Vang Pao (center, in camouflage), his staff, and American advisers, Laos 1969. Was Lolo Ernesto one of them? https://sofrep.com/58394/58394white-star/

Dr. Joe F. Leeker in his book History of Laos, he describes Air America:

“Air America looks like an operator whose flights had purely humanitarian objectives, it was another aspect of Air America’s activities in Laos that first became notorious and then famous: military and paramilitary support to pro-western forces said to have been done at the will of the CIA. Yet, it was not the CIA who came to Laos first, but the US military.”

According to the CIA’s public website, Air America in Laos from 1955-1974 wassecretly owned by the CIA, and was vital component in the Agency’s largest paramilitary operations in the country.

“For more than 13 years, the Agency directed native forces that fought major North Vietnamese units to a standstill. Although the country eventually fell to the Communists, the CIA remained proud of its accomplishments in Laos. As Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) Richard Helms later observed: ‘This was a major operation for the Agency. It took manpower; it took specially qualified manpower; it was dangerous; it was difficult.’” The CIA, Helms contended, did “a superb job.”

Mystery surrounds

After his work at Air America, Lolo Ernesto said “friends” brought him back to Thailand. His document showed that he worked as an English teacher and his office was also his home. It is registered as turakij suantuameaning, his own business.

If Lolo Ernesto was indeed employed by the CIA, he could have received a pension from the US government, according to a Dr. Sakt, a Thai historian and expert on ASEAN. Sakt also explained that Lolo Ernesto only needed to renew legal paper every five years. This type of documentation is issued as a sort of “diplomatic passport” where the holder can freely move in any country.

Lolo Ernesto said a woman, a “kind of official” supported him until she stopped visiting him in late February, prompting him to ask his neighbors for food.

In an email, Vice-Consul Jim Minglana said that the Philippine Embassy already sought the assistance of the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) “on procedures in handling the repatriation of elderly abandoned Filipino nationals upon their return to the Philippines.”

Lolo Ernesto could have told me more despite his dimming memory, but it all ended up with him asking me to bring him home. Where to? He only said “the Philippines,” where he wanted to rest.

Still, many unanswered questions linger.