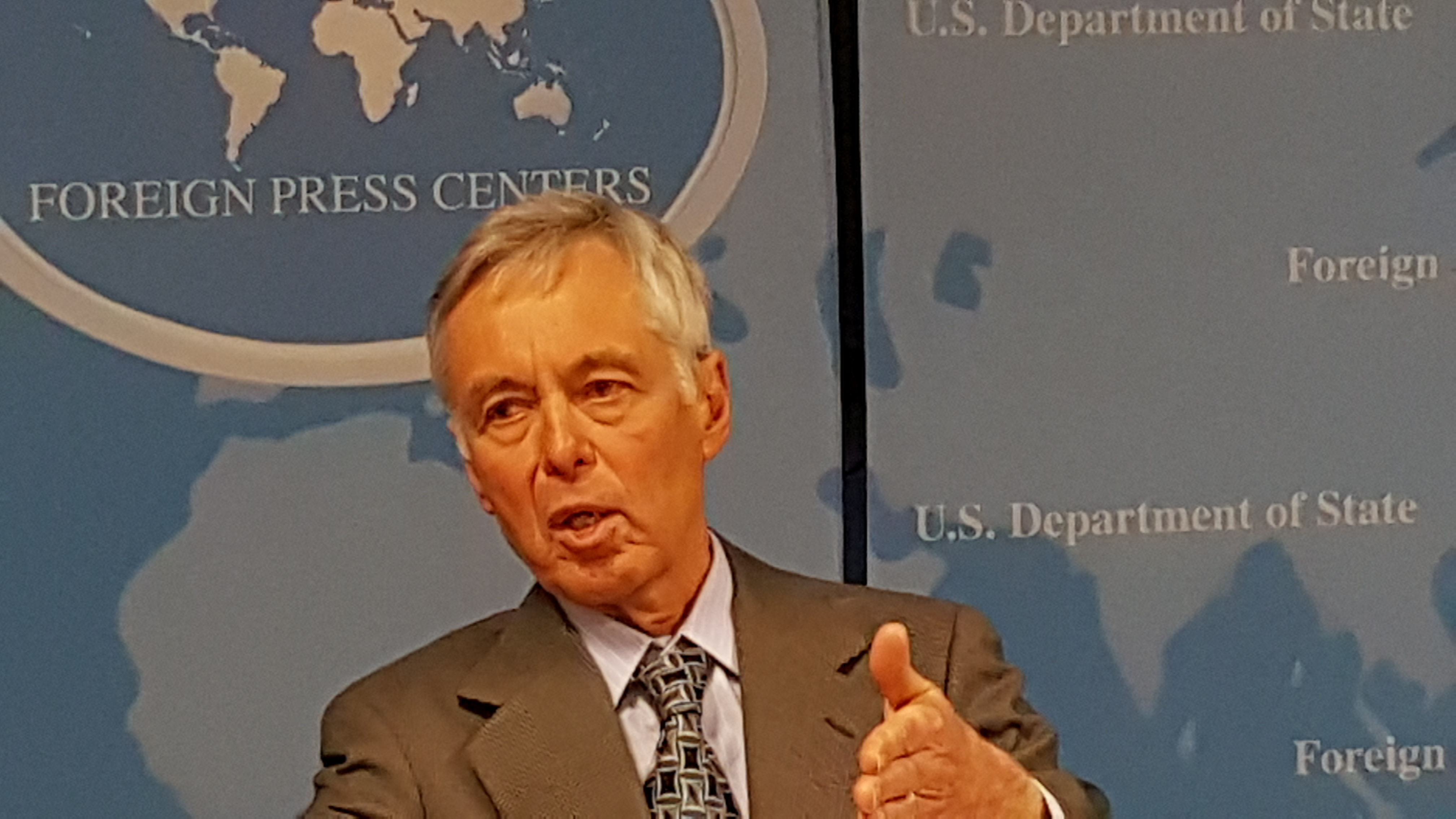

Professor Marvin Ott, PhD, a lecturer on East Asian studies at the Johns Hopkins University, says a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea would “delimit” China’s actions in the South China Sea. (PHOTO BY NIKKO DIZON/ INQUIRER)

WASHINGTON — Security experts here think it is unlikely that China would ever agree to a Code of Conduct among claimants in the South China Sea, such that having even just a framework this year, as the Philippine government is hoping for, is improbable.

In separate interviews, Marvin Ott, a scholar in Southeast Asia Studies at the Johns Hopkins University and Murray Hiebert of the Washington-based think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) said that China would make the negotiations drag on as it had for more than a decade.

“China will never agree to a real code of conduct,” said Ott, also a professor of national security policy at the National War College.

Ott said that the COC would not be useful to the Chinese.

An actual COC that governments would agree to would “circumscribe, delimit, and constrain China’s freedom of action in the South China Sea,” according to Ott.

Ott and Hiebert emphasized that the COC has been negotiated for the past several years.

And to talk and talk, and simply just talk, is what the Chinese simply intend to do, according to Ott and Hiebert.

“China will go another 15 years of talking if that is necessary,” Ott said.

The two experts separately met last week with 10 Filipino journalists, including the Philippine Daily Inquirer, who are part of the US State Department Foreign Press Centers reporting tour.

Murray Hiebert, deputy director of the Southeast Asian Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) says China’s goal is to make negotiations for the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea “drag on.” (PHOTO BY NIKKO DIZON / INQUIRER)

Hiebert, a CSIS senior adviser, said that not even President Duterte’s charm offensive to China could get a COC done this year.

“It is not the year to get it done. Can they get some basic framework done? It depends how you define framework. I think there is some possibility of getting progress, (but) I think this is still a long work in progress. I think China’s goal is to make this thing drag on for as long as possible,” Hiebert said.

China claims almost 90 percent of the resource-rich South China Sea through what it calls a nine-dash line, but which the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague had invalidated in a July 12 ruling last year that gave the Philippines a major legal — and moral– victory against its dominant northern neighbor.

China’s claim raises questions on freedom of navigation in the area that is a major trade route among nations.

Earlier last month, Foreign Affairs Secretary Perfecto Yasay expressed optimism that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) and China would conclude by mid-year a framework for the COC, a legally binding document aimed at easing tensions at the South China Sea.

Hiebert said that it was a good move by President Duterte to engage China soon after he took office in June but it should not have been at the cost of the Philippines’ victory at the PCA.

The strained relationship between China and the Philippines during the term of the President Benigno Aquino III was not for the Philippines’ long term interests, Hiebert said.

“To engage with them (Chinese) immediately was a good idea but not totally forgetting the ruling. I think Philippines would have had a few stronger cards in their hands if they mentioned it (ruling) a little bit more. China assumed that the Philippines has moved on,” Hiebert said.

Hiebert said the PCA ruling, a “hallmark, a trendsetter, that defined so much of what the situation is in the sea” would eventually be “forgotten.”

“It was a precedent and when there are other disputes, it could be brought out. But it’s going to be tough for the Philippines to walk this back,” Hiebert said. SFM